Who gets public money after natural disasters — and who doesn’t?

A new NPR investigation and analysis of previously unreleased Federal Emergency Management Agency data shows that, regardless of need, post-disaster government funds tend to favor the privileged over the poor.

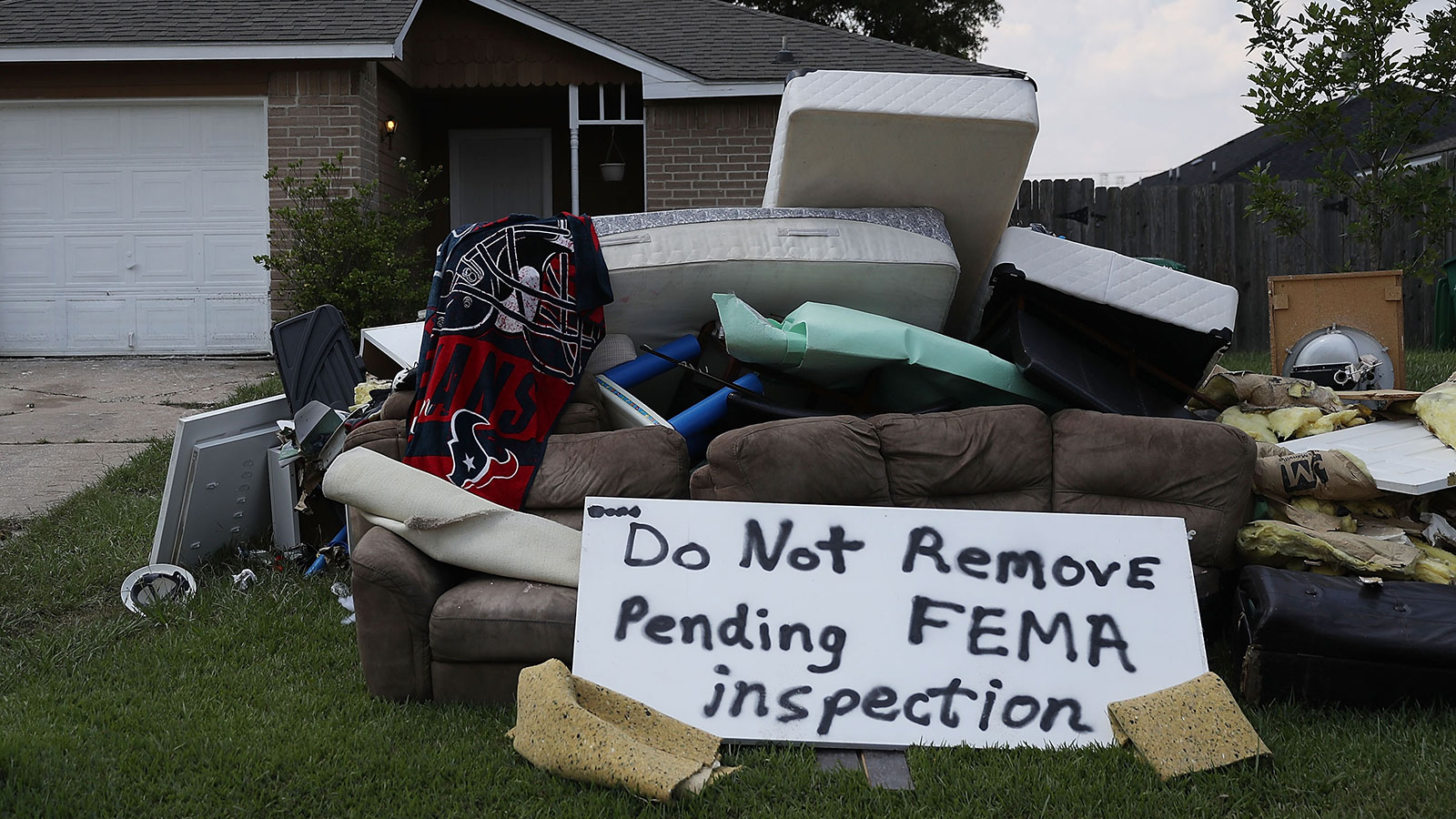

The story opens with the tale of two Houston families, both of which lost their homes due to storm-related flooding in 2017: a newly married, financially comfortable homeowning couple who received $30,000 in FEMA funds and more than $100,000 in tax refunds, and a family of renters consisting of a single mom and three kids, who were only given $2,500 in federal aid for a rental deposit.

The disparities in the two families’ financial situations only snowballed after the flood. While the wealthier couple was able to qualify for a low-interest loan to rebuild, the single mom landed in hot water with FEMA for choosing to use her funds on a vehicle for her family members to commute to work and school, and was not able to qualify for other sources of federal aid due to her low credit score.

“Cities are often very unequal to begin with,” says James Elliott, a sociologist at Rice University, told NPR. “They’re segregated and there are lots of income disparities, but what seems to happen after natural hazards hit is these things become exacerbated.”

Here are some of the investigation’s main takeaways:

- FEMA funds are calculated based on risk reduction — which means people with more money are more likely to get help. Federal disaster aid is allocated based on a cost-benefit calculation meant to minimize taxpayer risk. Thus, money is not necessarily given out to those who need it most; it’s doled out to those whose property is worth more, which means the system tends to favor those who live in whiter and higher-income neighborhoods.

- FEMA funding favors homeowners over renters. Due to FEMA’s cost-benefit calculation, poorer people, people of color, and people who are more likely to rent are less likely to get the much-needed cash after a major disaster. “Put another way, after a disaster, rich people get richer and poor people get poorer,” the investigation states. “And federal disaster spending appears to exacerbate that wealth inequality.”

- FEMA’s flood program has the biggest racial gap. NPR examined one particular federal program that buys out homes that have been flooded or otherwise impacted by natural disasters. Their investigation found that of more than 40,000 records in the FEMA database, most buyouts went to whiter communities (more than 85 percent white and non-Hispanic).

- Experts predict climate-driven disasters will become more frequent and severe. The Fourth National Climate Assessment, released last year, detailed the impending impacts of climate change across the country. Already, nearly 50 percent of U.S. counties experience a natural disaster each year, compared to fewer than 20 percent in the early to mid-20th century. “Hardworking Americans who are working class are going to find their communities stressed even more than they are now,” Andrew Light, an editor of the federal climate report told NPR. “If you’re already a community at risk, you’re going to be at more risk.”

As you might imagine, FEMA officials are none too pleased about the NPR investigation. A FEMA spokesperson provided the following statement:

“FEMA does not choose which properties participate in buyouts or acquisitions. Each state (grantee) works with their local governments to determine communities and residents who are interested in taking part of buyouts of repetitive loss properties. […] Each county floodplain manager and local officials know best the needs of their communities. We trust and support local and state officials during the buyouts process.”

Check out the entirety of the NPR FEMA investigation here.