It’s a little counterintuitive, but it turns out that having lots of intersections is really important for neighborhood walkability and transit use. A new study on Travel and the Built Environment by planning scholars Reid Ewing and Robert Cervero finds that “intersection density” is the single most important measurement for understanding what keeps folks out of cars.

Of all the built environment measurements, intersection density has the largest effect on walking – more than population density, distance to a store, distance to a transit stop, or jobs within one mile. Intersection density also has large effects on transit use and the amount of driving.

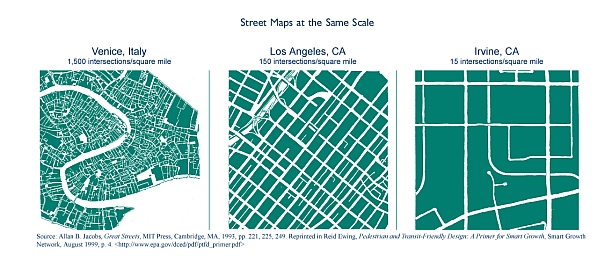

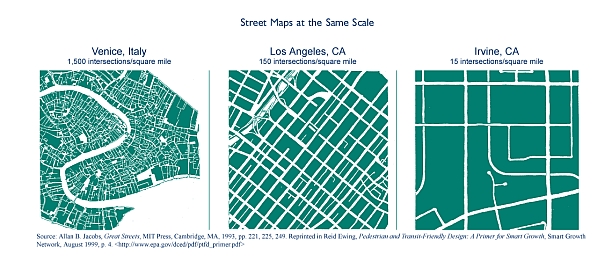

Visually: (Larger version)

(Larger version)

These images represent the same total area, yet differ vastly in how well streets connect to each other. More connections=more walkable. This is why Dave wants fewer dead ends in his own neighborhood when he puts on his city planner hat.

More good summary, with a slightly different focus, from Kaid Benfield, an influential Smart Growth blogger at NRDC:

The study’s key conclusion is that destination accessibility is by far the most important land use factor in determining a household or person’s amount of driving. To explain, ‘destination accessibility’ is a technical term that describes a given location’s distance from common trip destinations (and origins). It almost always favors central locations within a region; the closer a house, neighborhood or office is to downtown, the better its accessibility and the lower its rate of driving. The authors found that such locations can be almost as significant in reducing driving rates as other significant factors (e.g., neighborhood density, mixed land use, street design) combined.

The clear implication is that, to enable lifestyles with reduced driving, oil consumption and associated emissions, environmentalists should continue to stress opportunities for revitalization and redevelopment in centrally located neighborhoods. As Ewing and Cervero put it: ‘Almost any development in a central location is likely to generate less automobile travel than the best-designed, compact, mixed-use development in a remote location.‘

Benfield mentions a point I’ve been trying to address: “It also makes me wonder why more environmental groups, clearly incensed at BP and the Gulf oil spill, aren’t paying more attention to land use.” He’s right — transportation and land use are what climate policy looks like outside our front doors. Here’s how we get started at local levels.