You can bet an artist is grappling with questions of place and home and belonging when she belts out a line like, “Sometimes I wonder if the world’s so small / that we can never get away from the sprawl … Dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains / And there’s no end in sight.”

You can bet an artist is grappling with questions of place and home and belonging when she belts out a line like, “Sometimes I wonder if the world’s so small / that we can never get away from the sprawl … Dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains / And there’s no end in sight.”

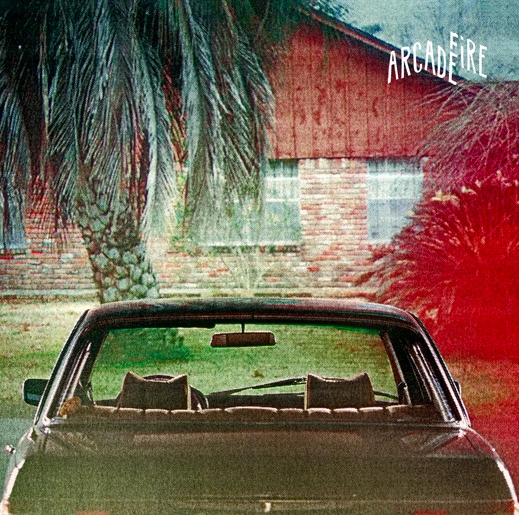

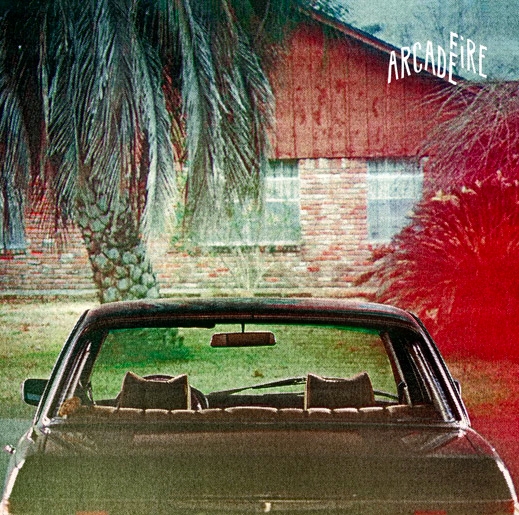

That’s Arcade Fire‘s Régine Chassagne singing on the tail end of the new album The Suburbs, which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts last month. It’s gotten plenty of well-deserved hype for taking on big literary themes and setting them to fabulous, soaring rock ‘n roll. It’s also got quite a bit to say about how our lives are shaped by the built environments we inhabit.

Quebec-native Chassagne and her husband, Houston-born Win Butler, take turns singing about growing up amid strip malls and tract homes, revisiting childhood neighborhoods as adults, and wondering where the hell they belong in a land of “endless suburbs stretched out thin and dead.”

But let’s be clear right off the bat: “The Suburbs” is not about Smart Growth. There are no hidden prescriptions for transit-oriented development (land-use planning rarely makes for good arena rock). There’s an unavoidable message here, but it isn’t clunky or didactic.

And neither is the album an ode to urban cool. Unlike, say, Green Day’s “Jesus of Suburbia,” it doesn’t take cheap shots at middle-age, middle-class conformity. In fact, Butler longs (he does a lot of longing) for a time before “the war against the suburbs.” He doesn’t take sides in the urban-suburban cultural divide, and the city doesn’t come across as the antidote to spiritual malaise. The bass-driven “City With No Children” seems to rejects the notion of city-as-yuppie-playground, suggesting that places thrive only when they accommodate people from all stages in life.

Here’s my bias: I grew up in the suburbs outside of Chicago. I was restless, bored, lonely, and hormone-addled there. Which is to say I was a teenager there. At the time I thought the suburbs were to blame for me being bored and restless; now I realize that some things about adolescence are the same everywhere.

Stockholm’s remarkable Hammarby Sjöstad neighborhoodBut I’ve also come to understand that how suburbs are built makes them an alienating environment. There are few public plazas, few front porches, few places to run into people on foot — and building a web of community requires these kinds of spontaneous, non-commercial conversations. It just doesn’t happen in cars. Durable green communities — places like Sweden’s Hammarby Sjostad, Vancouver’s UniverCity, Chicago’s Parkside of Old Town — are attempts to fix this uniquely modern social failure just as much as they are attempts to free us from fossil-fuel dependency.

Stockholm’s remarkable Hammarby Sjöstad neighborhoodBut I’ve also come to understand that how suburbs are built makes them an alienating environment. There are few public plazas, few front porches, few places to run into people on foot — and building a web of community requires these kinds of spontaneous, non-commercial conversations. It just doesn’t happen in cars. Durable green communities — places like Sweden’s Hammarby Sjostad, Vancouver’s UniverCity, Chicago’s Parkside of Old Town — are attempts to fix this uniquely modern social failure just as much as they are attempts to free us from fossil-fuel dependency.

Even cities in North America are mostly built for cars — perhaps why “The Suburbs” contains more seething (and gorgeous) discontent than celebration of successful places. Underneath that dissatisfaction, there’s resolve.

“If I could have it back,” Butler whispers on the closing track. “All the time that we wasted / I’d only waste it again … You know I’d love to waste it again.”

All that time stuck in traffic, playing video games, watching bad movies — whatever — it’s only “wasted” according to adult notions of productivity. The artist here knows something more: Those hours shaped him into who he is, a child of the suburbs determined to build something better.

Here’s “Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)”: