This is part of a series of posts on distributed renewable energy that will be posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

In less than a month, solar energy projects will see the stimulus-funded cash grant in lieu of the 30 percent tax credit expire. The change back to tax-credit-financed projects provides a revealing look at the disadvantages of energy incentives based on the tax code, thanks especially to a recent New York Times story about the shift. (For more on this subject, see “Why tax credits make lousy renewable energy policy.”)

First, tax credits induce prospective solar energy owners to sell their stake in the project to a financier who has the necessary tax liability. They still get solar, but not ownership:

Few commercial owners could come up with the capital expenditure necessary without the help of the 30 percent Treasury grant, said Jamie Hahn, a managing director at Solis Partners, a solar developer based in Manasquan, N.J. He said that after Congress established the grant program, the market for solar installations on commercial buildings changed from one in which the installations were mostly owned by investors, who then sold power back to building owners, to one where the business owners themselves did the installations.

“Prior to the cash grant coming out, about 70 percent of large-scale commercial solar projects were owned by third-party investors,” he said. “The cash grant made it feasible for actual building owners and companies themselves to own the solar assets.” [Emphasis mine.]

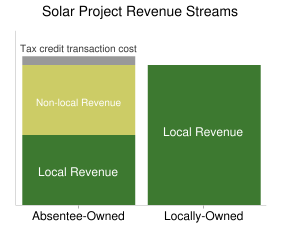

The difference isn’t just qualitative: the owner is the financial winner. Half or more of a project’s revenue accrues to a third party when a project developer requires an equity partner to use the tax credit. A residential solar lease is a good example. One company operating in Colorado provides a solar lease on a 5.25 kilowatt system for $5,000 upfront. Counting tax credits, the state rebate, and lease payments, only about 40 percent of the project’s revenue will accrue to the homeowner, with 60 percent to the leasing company[1].

The difference isn’t just qualitative: the owner is the financial winner. Half or more of a project’s revenue accrues to a third party when a project developer requires an equity partner to use the tax credit. A residential solar lease is a good example. One company operating in Colorado provides a solar lease on a 5.25 kilowatt system for $5,000 upfront. Counting tax credits, the state rebate, and lease payments, only about 40 percent of the project’s revenue will accrue to the homeowner, with 60 percent to the leasing company[1].

Whoever owns the system gets the most benefit, Mr. Hahn said. With federal, state and local subsidies, he said, the investment in a solar system can be extremely attractive. It can even generate income for the business, while locking in or providing free electricity for the 25 years the systems are typically under warranty.

It’s not just the owner who benefits when projects don’t require complex partnerships to get tax credits, but also ratepayers. As noted in a previous post, tax equity partnerships increase transaction costs, making solar power more expensive.

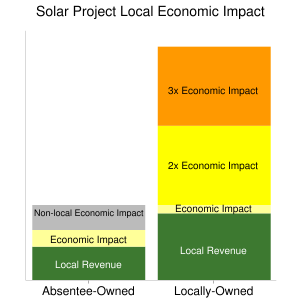

It doesn’t stop with owners or ratepayers. Communities or even states looking to boost their clean energy portfolio lose out on economic benefits. Locally owned projects provide one to three times the economic impact of absentee owned projects. Referencing our earlier example, a solar lease will send more than half of the local revenue away, reducing the economic impact by a multiplier, whereas local ownership would keep most revenues local.

It doesn’t stop with owners or ratepayers. Communities or even states looking to boost their clean energy portfolio lose out on economic benefits. Locally owned projects provide one to three times the economic impact of absentee owned projects. Referencing our earlier example, a solar lease will send more than half of the local revenue away, reducing the economic impact by a multiplier, whereas local ownership would keep most revenues local.

There are ways to improve the incentives for renewable energy, included in the latest attempt to extend the grant program (and also discussed in our 2008 report “Broadening Wind Energy Ownership by Changing Federal Incentives“). The Reid-Baucus bill for extending middle-class tax cuts offers a one year extension of the stimulus cash grant program, but converted to a refundable tax credit. This would offer a similar value to a cash grant but allow for broader participation in renewable energy projects than with the traditional tax credit.

The Reid-Baucus bill has another beneficial provision:

The outright ban on ownership by governmental entities and tax-exempts would be lifted. Instead, governments could receive the “credit” as could tax exempts (so long as they treated income from the facility as [unrelated business taxable income]).

Government and non-profit ownership could make a big difference in the local economic impact, since the former is often local by definition and the latter tends to have a mission to serve the local community.

Even better than a refundable tax credit would be an all-in cash payment for electricity from renewable systems, as is seen with a feed-in tariff. Not only does this reduce transaction costs, but it also pays for performance (on a per kilowatt-hour basis) rather than provide cash upfront. The feed-in tariff policy has been responsible for half the world’s wind power and three-quarters of the world’s solar power.

Note: Republicans filibustered the Reid-Baucus proposal on Saturday, effectively blocking both the refundable tax credit and ending the exemption for government and non-profit ownership. (Hat tip to Midwest Energy News.)

Endnotes:

[1]Solar leasing may be poor local economic development, but it’s not a bad deal for individuals. In the leasing example used above, the homeowner would have a 21 percent (inflation-adjusted) internal rate of return for a 25-year lease but a 7 percent IRR on 25 years of ownership. Of course, full ownership also means being responsible for a likely inverter replacement, as well as potentially receiving revenue for many years after the expiration of a 25-year lease.