The following essay and images are excerpted with permission from The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers, an iconic photo-documentary series shot by Rick Nahmias in 2002-03 and later published as a monograph.

Each morning, as early as 2 a.m., these women travel from Mexicali to the Calexico Port of Entry. They wait to board work buses that transport them as far as 75 miles north for their work in the cantaloupe fields of California’s Imperial Valley. Women comprise about 21 percent of America’s farmworker labor force.Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Each morning, as early as 2 a.m., these women travel from Mexicali to the Calexico Port of Entry. They wait to board work buses that transport them as far as 75 miles north for their work in the cantaloupe fields of California’s Imperial Valley. Women comprise about 21 percent of America’s farmworker labor force.Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

When envisioning California, most people conjure images of a warm, sea-sprayed coastline, redwood forests, the opulence of Beverly Hills, or the magic of Hollywood. It is easy to forget the farmland.

But California’s leading industry is actually agriculture, which provides about 50 percent of the produce consumed in this country, amassing $32 billion in annual cash revenue. To put this in perspective, this state’s earthly output is well over three times the combined annual domestic box-office receipts of the entire U.S. motion picture industry. This says nothing of the additional $100 billion in related economic activity that California agriculture generates.

Even easier to forget is that of the 36 million Californians, an estimated 1.1 million are farm laborers, without whom this state’s vital agriculture economy simply could not function. This virtually invisible underclass, whose days begin in darkness and involve unending hours of stooped labor under the blinding sun for wages that rarely amount to more than $10,000 a year, quite literally feeds our country.

Whether they are families living in the dirt lots of Mecca for months at a time during grape season; tomato pickers in Stockton who dash through muddy fields lugging 25-pound buckets in searing heat; day laborers who rise at 2 a.m. to cross the border at Calexico, only then to be bused 50 miles to the scorching onion and melon fields of the Imperial Valley; or workers of indigenous descent who are relegated to the lowest of the low in jobs and living conditions, each and every one of these people has a story.

Because of the transient, rural, and isolated lifestyles of migrants and the heavy and constant flow of undocumented workers that make up these vast harvesting armies, there is little public awareness of these people. As a result, farmworkers on the whole remain one of the easiest segments of our society to both cast off and exploit. For decades, though the languages they speak and their demographic make-up has changed, they have consistently endured our country’s greatest hardships in the areas of healthcare, unlivable housing conditions, and workplace treatment and safety.

By virtue of the seasonal work they do and how they are employed — often traveling with one particular type of fruit or vegetable throughout an entire harvest — few call any one place home for more than a couple of months at a time. This not only keeps farmworkers on the outside of the communities in which they live, but also splinters families and prevents the growth of meaningful roots. It erodes any firm toehold they may get with which to negotiate for better conditions with the growers or the farm labor contractors.

There are glimmers of hope. Though theirs is an existence rife with struggle, it is this very constant push for survival that drives many toward inventing opportunity for themselves and their families. Grassroots organizations have emerged aimed at curtailing domestic abuse and sexual harassment, family recreation centers have been created where social services can be based and easily accessed, and countless unsung heroes and advocates in the farmworker community have worked tirelessly to imbue this population with a sense of pride and possibility.

There may always be controversy about the machinations of the political power that provides and controls cheap labor and about the status of farmworkers — whether they should be naturalized, how they should be treated, paid, housed, and who ultimately is responsible for their well-being. The Migrant Project photo-documentary series sets out to do one thing: to put human faces to the people who, in the inimitable words of Edward R. Murrow, “harvest the food for the best fed nation in the world.”

While traveling nearly 4,000 miles across the state to photograph more than 40 towns during five months, two things became evident: 1) there is no other sector in our country where people have to work so hard to have so little, and 2) by adjusting our mentality to one of inclusion and respect, we can welcome farmworkers as a meaningful part of our society and understand their intrinsic value, not just for the essential work they perform, but as human beings and individuals who each carry with them the same hopes of many Americans — the dream of a better life.

In absorbing the photographs and stories on the following pages, we take the first step in doing just that. (Check out the slideshow in Spanish here / Echa un vistazo a la presentación de diapositivas.)

©Rick Nahmias/All Rights Reserved

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Grape worker Guillermina Sanchez arrives at the vineyards in the dark and begins work as the moon sets. She is also member of Lideres Campesinas, a statewide grassroots organization of farm-working women who do outreach to their respective communities on issues of importance to the farmworker communities, including pesticide danger, domestic abuse, and HIV. A recent survey revealed 60 percent of the surveyed farmworkers in the Coachella Valley — the first California region to harvest table grapes each year — reported they were required to “test the fruit” by eating unwashed grapes during the harvest to find out if they were sweet enough to be picked. This practice is not regulated under California pesticide law.

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

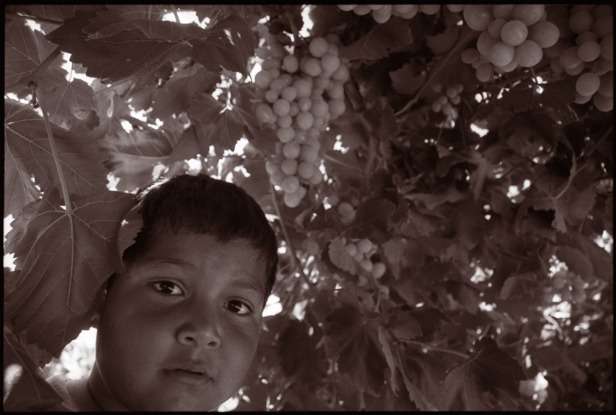

Victor Hernandez, a 6-year-old boy from Coachella, takes some time on his summer break from school to visit the vineyards with his mother, a community worker.

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

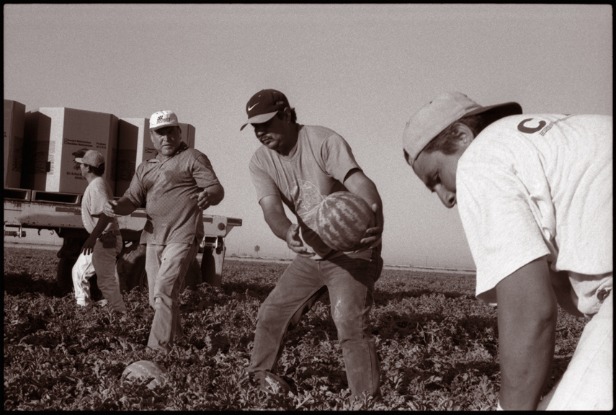

This eight-man migrant team from Texas earns $10 per ton each of watermelon pitched. They estimate that on a good day they make $80 each for six hours of work. This comes out to eight tons of melon tossed per man, per day, without the aid of back braces, gloves, or any other safety equipment.

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

The green tomato harvest is done entirely by hand. Farmworkers pick the fruit as fast as possible, tossing it into two buckets, which they then run to trailers. These green or “fresh market” tomatoes are then treated with ethylene gas to bring about the bright red color. This is among the dirtiest types of fieldwork, and several layers of clothing are worn to keep workers both protected from the sun and dry from the mud they crawl through. Gloves are worn for quicker and easier handling of the fruit.

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Photo: (C) Rick Nahmias/themigrantproject.com

Tomato workers are given one token for each pair of buckets they fill, with each pail weighing approximately 25 pounds. The value of the tokens fluctuates with the market price of the tomatoes. On this day, the tokens were worth $0.95.