When I had a free afternoon during my recent trip to Berlin, I headed down Unter den Linden (I love German street names — my hotel was on the Albrechtstraße, which is a whole meal in a word) to the relatively new DDR Museum, which showcases ordinary life under socialist rule in East Germany. It’s a fascinating place. It doesn’t downplay the crushing conformity imposed on living quarters, cars, and work conditions under the German Democratic Republic (GDR), but it still shows the idiosyncrasies and spirit that no regime can ever entirely suppress. If you’re in Berlin, I recommend it.

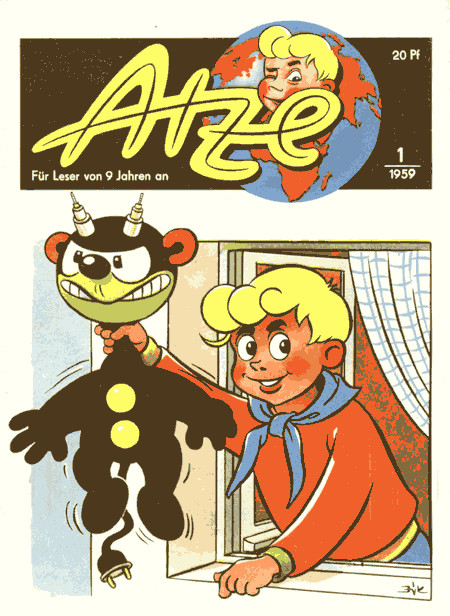

Strangle creepily ethnic looking Wattfraß, Aryan-looking boy!Source: Energy Saving MuseumOne of the most interesting aspects was finding out how central environmental consciousness was to the rise and fall of socialism in Germany. When the GDR was founded, one of its many promises to workers was clean working conditions, without the polluted air and water imposed by capitalist industrialization. There were legal safeguards and fines on polluters. The regime was quite energy conscious, at least in the beginning. In the late 1950s, for instance, there was a popular comic strip character called Wattfraß with isolators on its head and a plug on its rear that was created to encourage children not to waste energy. (Note child strangling Wattfraß to the right there. At the linked page, there’s another of the child skewering Wattfraß on a pitchfork.) Environmental stewardship was written into the constitution in 1968.

Strangle creepily ethnic looking Wattfraß, Aryan-looking boy!Source: Energy Saving MuseumOne of the most interesting aspects was finding out how central environmental consciousness was to the rise and fall of socialism in Germany. When the GDR was founded, one of its many promises to workers was clean working conditions, without the polluted air and water imposed by capitalist industrialization. There were legal safeguards and fines on polluters. The regime was quite energy conscious, at least in the beginning. In the late 1950s, for instance, there was a popular comic strip character called Wattfraß with isolators on its head and a plug on its rear that was created to encourage children not to waste energy. (Note child strangling Wattfraß to the right there. At the linked page, there’s another of the child skewering Wattfraß on a pitchfork.) Environmental stewardship was written into the constitution in 1968.

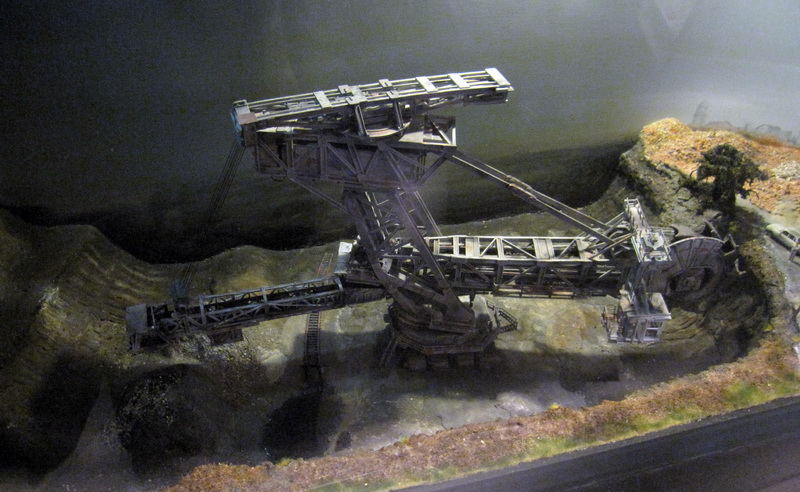

Of course, that promise, like all the others, was broken. Things went south quickly as the GDR became dependent on the region’s filthy brown coal (lignite). Here’s one of the first sights that greets visitors to the museum — a model of a huge coal-mining machine:

The machine that ate East Germany.Source: DDR Museum

The machine that ate East Germany.Source: DDR Museum

Delightful.

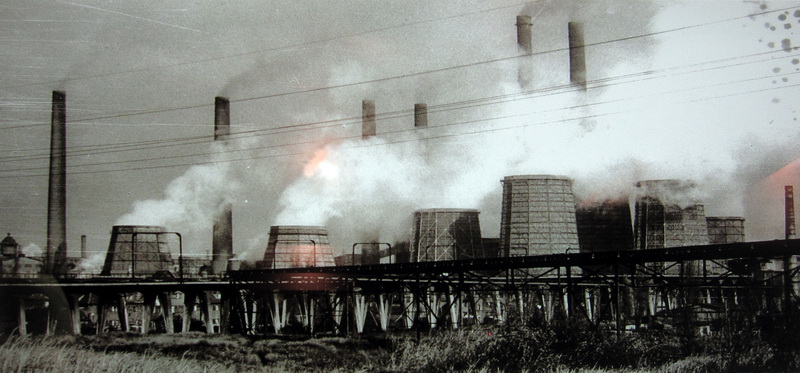

Over time, there was very little innovation, environmental standards fell away, and the need for industrial output increased. Between coal and chemicals, the situation got worse and worse until several German towns were completely obscured in dark soot, people were choking and dying of respiratory illnesses, and so on.

Bitterfeld, Germany, home of a chemical complex, mid-1970s.Source: DDR Museum

Bitterfeld, Germany, home of a chemical complex, mid-1970s.Source: DDR Museum

This story of degradation and ill health did not serve the GDR well, so in 1982 the council of ministers officially deemed all environmental data confidential, a state secret. This, as much as any other act by the regime, inspired grassroots resistance, expressed by a profusion of DIY pamphlets on civil rights and ecology.

Members of the Environmental Library, photographed by the Stasi on the night of their arrest, 24-25 November 1987, during a search of the premises.Source: Peaceful Revolution 89/90In 1987, the Stasi broke into the basement of the East Berlin Zion Church and shut down the Umwelt-Bibliothek, or Environmental Library, an underground educational institution meant to to promote discussion of suppressed or censored material. Such groups, often taking shelter in churches, had operated since the mid-’70s. The library used an old printing press to distribute its own magazine, which came to be known as Umweltblätter, or “environmental letters.” The circulation reached 2,000 before it was shut down.

Members of the Environmental Library, photographed by the Stasi on the night of their arrest, 24-25 November 1987, during a search of the premises.Source: Peaceful Revolution 89/90In 1987, the Stasi broke into the basement of the East Berlin Zion Church and shut down the Umwelt-Bibliothek, or Environmental Library, an underground educational institution meant to to promote discussion of suppressed or censored material. Such groups, often taking shelter in churches, had operated since the mid-’70s. The library used an old printing press to distribute its own magazine, which came to be known as Umweltblätter, or “environmental letters.” The circulation reached 2,000 before it was shut down.

I should probably be careful about drawing any Grand Conclusions. There’s a deep history around this stuff in Germany and I’m far from an expert on it. But I can’t resist a few observations.

First, what happened to industry under GDR is what happens when decisions are controlled by a small group of people, usually people who own — or have financial or political ties to those who own — the means of production. The focus inevitably turns to rapid growth, gigantism, pollution, and profits. The poor and defenseless (a large class in the GDR) have no voice and so they suffer while a small group benefits. Those who profit always claim to be acting in the public interest, but given a real choice, the public puts a far higher premium on health and safety.

Now, here in America we don’t live under a communist dictatorship. So that’s good. But if there’s one sector of our economy that comes closest to socialism, it’s energy. Decisions are made by a small group of owners, regulators, and politicians; there’s nothing approximating a free market and very little in the way of public participation.

Sure enough, the results tend toward the big, dirty, and hostile to regulatory constraints. This kind of centralization and gigantism has become so familiar to us in energy that we scarcely notice it. We have become accustomed to thinking of our future in terms of ever-rising demand and ever-larger power plants (despite the recent failures of that approach).

Solar village in Freiburg.Source: TreehuggerBut when communities own their own means of energy production, when they live next to it, they are willing to pay extra and consume more conscientiously in exchange for cleanliness. Something new is happening in Germany now: Of all the country’s renewable energy, just 4 percent is owned by the four big utilities. The remaining 96 percent is owned by private households, small municipal utilities, rural and energy cooperatives, and people’s wind parks.

Solar village in Freiburg.Source: TreehuggerBut when communities own their own means of energy production, when they live next to it, they are willing to pay extra and consume more conscientiously in exchange for cleanliness. Something new is happening in Germany now: Of all the country’s renewable energy, just 4 percent is owned by the four big utilities. The remaining 96 percent is owned by private households, small municipal utilities, rural and energy cooperatives, and people’s wind parks.

In Germany, the power oligopoly has competition. It is the beginning (only the beginning) of energy democracy: a safer, cleaner, more human-scale energy system. Some 25 years after it was shut down, the Umweltblätter is bearing fruit.