I’d love to tell you about my summer close to nature — how I whiled away the days on a hidden Maine-coast isle, picking blueberries in the early morning and watching seals cavort in the sea. But the truth is, I spent quite a few of my July and August afternoons in a different sort of island haven: the dark, air-conditioned movie theaters of Manhattan.

There’s something dissolute about going to a movie on a sunny afternoon. A little devil whispers into your ear that it’s just plain wrong to reject the fair weather — healthy outdoor sports, cheery communal picnics, glorious sunlit nature — in favor of a couple of asocial hours in a darkened movie house. And double the shame if you’re an eco-geek who’s supposed to be out communing with Gaia.

But fortunately for my ample guilt complex, nature was in unusually good supply in the movie houses this summer. The season’s epic good-versus-evil showdown wasn’t Obi-Wan versus Anakin — it was flightless waterfowl versus ursine killers. Two independently produced nature documentaries were vying for the title of best summer flick, and moviegoers got an eyeful.

This is what reality looks like.

Penguin Photos: Jérôme Maison.

Bonne Pioche Productions / Alliance De

Production Cinématographique.

Both March of the Penguins and Grizzly Man are do-it-yourself media writ large and gorgeous and passionate — the antithesis of most of this summer’s well-chewed blockbusters. They look fresh, they have energy. As New York Times critic Stephen Holden wrote recently in a sort of tribute to their power, they “challenge audiences to examine reality at a moment when the very term has been warped beyond recognition by reality television.” And both convey a certain insane level of dedication to getting something good on film.

In Penguins, director Luc Jacquet and his team spent more than a year trundling through the blizzards, ice, and severe temperatures of Antarctica with cumbersome cameras. They emerged with what might be the year’s most beautiful film. Jacquet spins a moral fable of love, loyalty, and bravery out of the mating habits of emperor penguins; even though it’s nonfiction, it’s squarely in the tradition of uplifting critters-as-people stories like Watership Down or The Incredible Journey.

As we watch, the penguins leave their home at continent’s edge and march, like a line of stout, well-dressed Himalayan trekkers, to a safer mating ground 70 miles inland. The ensuing coupling, nurturing, and repeated trips to and from the ocean to feed surely ranks as one of nature’s most arduous solutions to perpetuating a species.

Behind the scenes.

The movie doesn’t shy away from danger and death, but Morgan Freeman’s warm, fatherly narration imposes order, transforming the penguins into the best possible version of us: simpler, purer, more devoted to their families and friends. The movie has even been embraced, the somewhat-obsessed Times also tells us, by Christian leaders who say it affirms the values of monogamy and intelligent design (not, says Jacquet, his intention). Penguins is thus the ultimate combination of nature porn and bedtime story — and the summer’s breakout hit. Whether people really think penguins fall in love or not, the film — which cost about $7 million to make — has grossed nearly $67 million since being released in the U.S. on June 25. It recently displaced Bowling for Columbine to become the second-highest-grossing documentary in film history — right behind Fahrenheit 9/11.

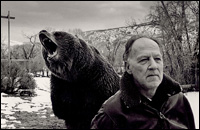

If Penguins is the documentary equivalent of Free Willy, then Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man is Moby-Dick. It tells a much darker tale, but ends up being just as much about the meanings that humans project onto nature.

Werner Herzog and friend.

Photo: Lena Herzog.

Herzog, no stranger to stories of men undone by their obsessions, layers his acid commentary over amateur video shot by Timothy Treadwell, the film’s namesake. Treadwell was a Long Island-to-Hollywood transplant blessed with a surfer’s good looks and exterior hippie amiability, but beset by substance addiction and a lengthening string of professional and personal disappointments. In his early 30s, he traveled to Alaska and found the perfect foil to his heart’s darkness: the grizzly bears of Katmai National Park and Preserve.

He went on to spend 13 summers tramping, camping, and trying to befriend Katmai’s grizzlies — and videotaping his own exploits for self-aggrandizement back in the Lower 48. In the process, he achieved the success and fame that had eluded him elsewhere, complete with a guest appearance on Letterman. But eventually he crossed a line; he tried to become a bear among bears. On an October day in 2003, one of his fellow creatures ate him.

Treadwell’s home video is unfailingly personal, earnest, and sometimes accidentally artistic — such as a scene when he exits the frame and leaves the camera running, recording the quiet visual poetry of leaves and grasses in the Arctic breeze. He shoots take after obsessive take summing up his adventures for the audience, to ensure he’ll have good material for editing later on — it’s Wild America meets America’s Funniest Home Videos. But the real power of Grizzly Man comes in Herzog’s keen judgment of how to use this footage. The German filmmaker interviews Treadwell’s friends, family, associates, even coroner, and combines those conversations with his tart observations to transform Treadwell into an archetype of self-invention and self-destruction in the American wilderness.

Treadwell looked for deliverance in nature, and saw benevolence in the eyes of the bear. Herzog sees chaos in nature, and regards that look in the bear’s eye as an indifferent, barely disguised interest in its next meal. Grizzly fascinates in part because it exposes not one, but two highly subjective views of the wild.

It’s a double vision that, though it hasn’t raked in as much as its cuddly counterpart — $2 million in the month since it opened — is being widely hailed as a great film, the kind that will leave you and your friends debating humanity’s relationship with nature. Meanwhile, Penguins has easily waddled away with the summer box office, its opening-weekend per-screen average beating Batman Begins and Mr. and Mrs. Smith combined.

So does the popularity of these two movies, as Holden suggested, herald a cultural shift? Does their success suggest a new vogue for big-screen nature documentaries? Or was it just that the ice of Antarctica and the wilds of Alaska provided sweet summer relief? Whatever the case, I’m looking forward to more of the same — it’s the only way I can spend all those guilt-free afternoons hiding from the sun.