No less an investor than the mighty Warren Buffett has proclaimed that the decline of coal in the U.S. will be gradual but inevitable. Given flat demand for electricity, cheap natural gas, burgeoning renewables, rising efficiency, and future carbon regulations, new coal-fired power plants are bad bet, which is why they aren’t getting built.

To save their bacon, U.S. coal mining companies want to export their coal to hungrier markets, mainly Asian markets. OK, mainly China. Demand for coal in China is a crucial justification for the export infrastructure coal companies want to build in the Pacific Northwest — export terminals in Oregon and Washington that would handle coal shipped by train from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. (Activists are battling those plans, with some success. A similar fight is happening in British Columbia.)

But overseas demand for thermal coal — the kind used in power plants — has been overestimated. New investments in thermal coal infrastructure, unless they come online quickly, will miss a rapidly closing window for profitability. In coming years, there won’t be enough demand growth to justify such investments.

That’s the explosive conclusion of a report recently issued by analysts at Goldman Sachs. (It’s not public, so I can’t link to it.) The implication for coal-export projects in the Pacific Northwest is clear: They are bum investments. You don’t need to share concerns over climate change to see it. Just economics.

——

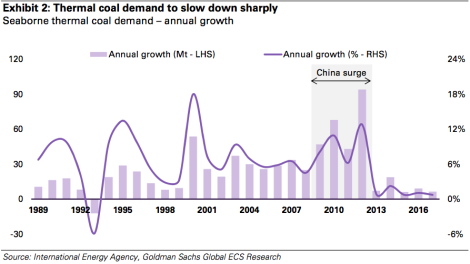

For roughly the past decade, thermal coal has been on a global growth spree, mostly driven by meteoric demand out of China:

Over the period 1990-2011, global demand [for thermal coal] increased by 2.5 billion tonnes, equivalent to an average annual growth rate of 3.0%. However, growth was highly concentrated in just two countries: China alone accounted for 72% of the global increase in coal burn, while India accounted for an additional 17%. Excluding those 2 countries, global consumption was only growing at an annual rate of 0.7% per year.

Nonetheless, China’s boom drove coal to global dominance. It is now the top global source of fuel for electricity and just a hair behind oil as top global energy source, period.

But it looks like China’s growth boom is over and, with it, the boom in thermal coal. China is spending billions to control air pollution, banning imports of low-grade coal, launching carbon-trading markets, exploring shale gas, getting more efficient, and building the crap out of renewables. And remember, it has its own coal mines. They just couldn’t keep up with the boom. Now that things are leveling off, domestic Chinese coal will get cheaper, they’ll buy more of it at home, and there will be less market for imports.

Since China was the main driver, its rapid deceleration will serve as a drag on the whole seaborne coal market. Goldman Sachs analysts “expect average annual growth to decline to 1% in 2013-17 from 7% in 2007-12.”

That’s a pretty steep drop-off. And 1 percent growth is pretty low.

The forces pushing against coal are not confined to China, of course. They are global. Here’s Goldman Sachs’ compact explanation:

We believe that thermal coal’s current position atop the fuel mix for global power generation will be gradually eroded by the following structural trends: 1) environmental regulations that discourage coal-fired generation, 2) strong competition from gas and renewable energy and 3) improvements in energy efficiency.

And here is their stark conclusion:

The prospect of weaker demand growth (we believe seaborne demand could peak in 2020) and seaborne prices near marginal production costs suggest that most thermal coal growth projects will struggle to earn a positive return for their owners. [my emphasis]

Coal mining and infrastructure investments have a 40-year time horizon. They take a long time to build and they operate for a long time. Those long time horizons mean huge risks, especially given the trends described above. If you were an investor, how much would you bet that there will be no serious climate legislation in the next 40 years?

Trajectories will differ in different regions, but the overall direction is clear. Goldman Sachs forecasts that there will not be enough global demand to justify even the large-scale coal exploitation projects already in the pipeline. There are major fields under development not only in the Powder River Basin but in Africa, Indonesia, and Australia. They’re all going to be coming online and competing with one another in a market where demand growth has slowed to a crawl. It does not bode well for them.

Pretty much the only thing that could save thermal coal is a huge spike in natural gas prices, a huge drop-off in renewables and efficiency investments, or the emergence of affordable carbon capture and sequestration. Most analysts find those scenarios implausible. What do the coal mining companies themselves think? To find out, Goldman Sachs took a look at four diversified mining companies (i.e., companies with investments outside of thermal coal as well). How are they shifting their assets internally?

At its peak in 2006-10, thermal coal absorbed up to 12% of the aggregate growth capital across these companies. However, we expect that share to decline in both absolute (down 50% between 2013 and 2016) and relative terms (down to 7% by 2016), according to our estimates.

Companies that can are moving slowly away from thermal coal.

——

The consequences of all this for coal-export projects in the Pacific Northwest should be obvious. By the time they could be built, assuming they overwhelm local resistance, they will enter a mature market facing oversupply problems. If there’s anything worse than befouling some of the most beautiful places in the country for shot of fossil-fuel money, it’s befouling them for nothing.

Northwest coal-export infrastructure is, in addition to being immoral and unconscionable, a terrible investment.