Texas is home to 28 oil refineries, more than any other state, along with half of U.S. chemical manufacturing. Most of these facilities are clustered along the Gulf Coast, where Hurricane Harvey just dumped a year’s worth of rain in a few days.

For the neighborhoods bordering Houston’s industrial facilities, an average day brings air polluted with nitrogen oxide, benzene, sulfur dioxide, and other harmful byproducts of the manufacturing processes that drive the city’s economic engine. People in these communities face cancer rates more than 20 percent higher than the city as a whole.

When Harvey forced many of these power plants and refineries to shut down, huge quantities of toxic chemicals — as much as 2 million pounds of them — were released into the air all at once. Nearby residents reported “unbearable” smells, and some were even told to “shelter in place” as authorities weighed the necessity of evacuation amid rising floodwaters.

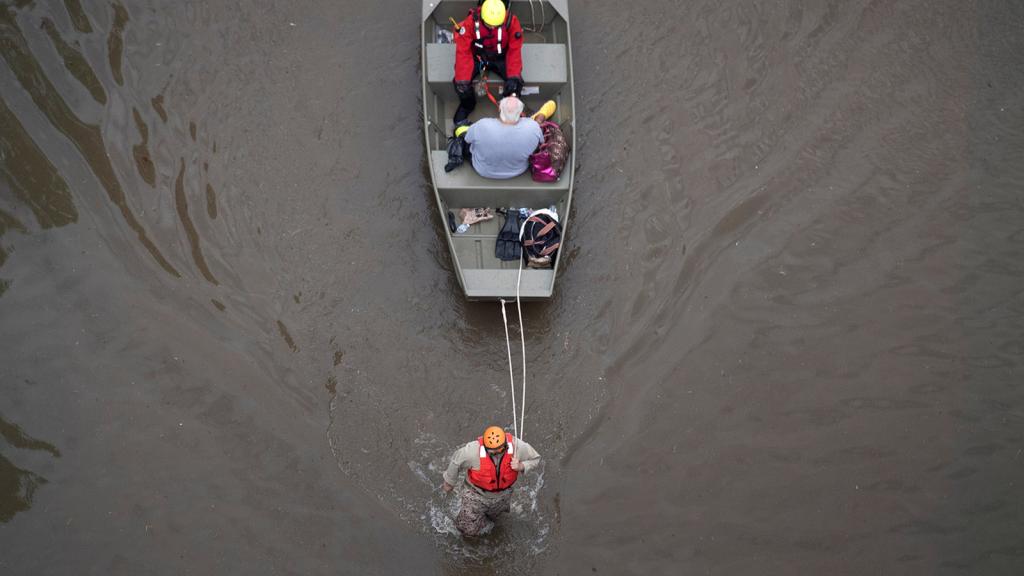

The waters, of course, brought their own dangers. Storms often wash untreated sewage into the streets, carrying a risk of disease. Harvey’s historic flooding also brought pollution from flooded factories, refineries, plants, and Superfund sites.

The EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory catalogued 1,816 sites with harmful pollution in the state of Texas in 2015; 495 of those fall within the greater Houston metropolitan area, responsible for a cumulative 1.5 billion pounds of toxic waste a year. Many of these sites rely on containment ponds and storage tanks where hazardous materials are held until they can be treated and discharged — but as the storm overwhelmed infrastructure and flooded these sites, those concentrated pools of toxins were likely mixed into the floodwaters.

“There’s no need to test it,” one Houston Health department official told the New York Times. “It’s contaminated. There’s millions of contaminants.”

There’s a lot we don’t know about the chemicals released during the storm — air monitors were turned off, and water sampling is only just beginning. There is, however, practical advice to dispense: Avoid touching floodwater — if you can — and wash any areas and discard any food that came into contact with it. In some affected areas, officials have warned residents to boil their tap water or avoid altogether. Some groundwater wells may be contaminated indefinitely.

We assembled a rundown on some of the oil-derived contaminants swirling around Houston’s water and air right now:

Creosote

Houston’s Harris County is home to more than 20 Superfund sites, and many of these old industrial areas are steeped in decades-worth of toxic substances — like creosote. It’s a petroleum-derived product used to waterproof wood. (It’s what gives telephone poles and railroad ties that particular, and carcinogenic, smell.) Creosote contains hundreds of chemicals, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and phenols, both of which can cause cancer and mutations, especially in developing embryos or fetuses.

Along with creosote, lead, arsenic, and heavy metals may be stirred up from Houston’s old industrial sites. After Hurricane Katrina, elevated lead levels were found in New Orleans’ soil, says Cyn Sartou of the Gulf Restoration Network, possibly due to floodwaters that resuspended and distributed the toxic material.

Benzene

The EPA classifies benzene as a PBT, a “persistent bioaccumulative toxin.” That means it sticks around in the environment for a long time, builds up in the food chain, and, yes, is toxic. Benzene exposure is linked to cancer in humans. A natural ingredient of crude oil, it is also often released during the process that turns oil into rubber. Overall, in Texas, 4 million pounds of benzene were released into the environment in 2015.

“A toxicologist who’s honest and independent will say the only safe limit of exposure is zero,” says Neil Carmen, clean air director for the Texas Sierra Club chapter, about benzene. “When you start talking about anything more than that, you’re just talking about more exposure to risk.”

Sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide is a common product of power plant smokestacks, and one of the main components of smog. Short term exposure can cause difficulty breathing, which is especially dangerous for the elderly or people with asthma. At an ExxonMobil refinery in Beaumont, Texas, storm damage led to the release of more than 1,300 pounds of sulfur dioxide. Another plant in Corpus Christi reported a release of 15,000 pounds.

Power plants usually have to obey limits on how much sulfur dioxide they emit, but these caps are often discarded during emergency situations. Since traditional plants are designed never to be turned off, shutting down essential processes can take several hours and release huge amounts of these harmful gases in so-called “unplanned events.” And when the plants start back up again, they’ll release more. Other gases in these plumes can include carbon monoxide, butane, propane, ethylene, particulate matter, and a nasty carcinogen called 1,3-butadiene.

And at the moment, Arkema’s malfunctioning chemical plant in the town of Crosby is on fire. The plant’s organic peroxides, used in plastic manufacturing, tend to go boom when they warm up, which they’ve been doing since the plant’s refrigerators failed and fires were reported on Thursday. In the company’s worst-case scenario, an explosion could release 66,260 pounds of sulfur dioxide, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

Oil

An oil spill may seem tame compared to carcinogenic benzene or mutagenic creosote, but oil in its various forms can cause skin irritation, lung inflammation, and a whole slew of other problems up to, and including, death. At least two ExxonMobil refineries were damaged during the storm, the fossil fuel giant announced Tuesday, leading to the release of some (unknown) quantity of some (undisclosed) substance.

Dioxin

Dioxin is the chemical responsible for the deaths and deformities stemming from the United States’ application of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. An extraordinarily small dose — the size of the period on your screen, say — can trigger a fatal reaction in humans.

In the 1960’s, when Houston was home to many paper mills, one major byproduct was dioxin. Much of the mills’ dioxin waste ended up in pits along the San Jacinto River. Now a Superfund site, the San Jacinto pits flood periodically, dosing the groundwater and the seafood-rich Gulf with deadly poison. During Harvey, the site was said to be underwater again. That means floodwaters could carry dioxin-contaminated sediment into parts of the city that have never been contaminated before, putting people at huge risk of exposure.

Harvey created a huge mess in southeastern Texas. It’s hard to imagine chemical clean-up efforts making much headway until more immediate threats are addressed. It will be a long time before the long-term effects of all these contaminants become clear, but they could be catastrophic for residents who already face elevated risk of disease thanks to chronic exposure to these substances.

“We’re never going to adequately regulate these plants so they’re not harming people, and killing them,” Carmen of the the Texas Sierra Club says.

If we really wanted to do that, we’d have to treat oil refineries and chemical plants the way we treat nuclear plants — by capping them with thick concrete domes to collect all of the toxic emissions and treat them. That’s too expensive to be feasible, Carmen explains, and so far, fossil fuel companies have just gotten away with dumping this stuff in communities that often have no political power to stop them.

“I call ‘clean’ zero: no air emissions, no toxic nothing in the wastewater,” he says. “But maybe that’s 22nd century technology.”