On a recent afternoon, Beth White, CEO of the nonprofit Houston Parks Board, steps onto a trail along Brays Bayou in the southeastern part of the city. There are 12 major bayous in Harris County, connecting 22 watersheds to the Gulf of Mexico. The waterways are a defining feature of America’s fourth-largest metropolis, giving it 2,500 miles of waterfront and the moniker “the Bayou City.”

When they flood, as they did during Hurricane Harvey in August, so does Houston.

White is walking near a meandering part of the Brays in the neighborhood of Idylwood. Bikers and skateboarders zip by. Pelicans fly above and dive into the water for fish. Harris County Flood Control District finished expanding this section of the Brays in 2007. Parks Board, a local nonprofit that advocates for green space, completed trails here in 2014, adding a kayak ramp and native plants as part of its Bayou Greenways 2020 project.

White sees her job, in part, as assuring Houstonians that “it’s OK to be down here.” Over years of neglect, bayous were less a destination to see nature and more akin to a freeway underpass. Today, Brays Bayou is increasingly lush.

The waterways are getting greener for a lot of reasons, reflecting broader shifts in how urban residents envision their surroundings and how local officials manage flooding. As Houston recovers from Harvey, they offer a promising vision of a city — that has for decades prioritized development over nature — living in harmony with its rivers.

Founded in June 1837, the city of Houston promptly flooded four months later thanks to a hurricane.

John Jacob, director of the Texas Coastal Watershed Program at Texas A&M University, believes that Houston’s floods don’t have to be so severe. His research suggests that different natural features, like wetlands and reservoirs, help to mitigate flooding.

Jacob wrote a popular blog post for the Texas Coastal Watershed Program after Harvey, outlining these points. “Why not build a magical city served by beautiful and functional green infrastructure?” he asked.

But there’s a limit to how much nature can mitigate problems created, well, by nature, says Gary Zika, a project manager at Flood Control overseeing work on the Brays. “There was always flooding in Houston, whether there were prairies here or forests,” he adds.

The Bayou Greenways project is based on a plan from 1912 to connect Houston’s bayous with park space. One hundred years after that proposal, residents finally voted to fund it. Since, Parks Board has acquired 223 acres of new green space, is opening more than 3,000 acres up to the public, and has built and connected trails on basically every major bayou in Houston.*

The effort is not the only project of its kind. On the opposite side of Houston, Flood Control is also working on Willow Waterhole — a group of detention ponds surrounded by parks and native habitat. While that widely acclaimed effort has made southwest Houston greener, it also gives floodwaters in the area somewhere to go besides homes and businesses — which is why Flood Control’s involved.

The agency hasn’t always favored green solutions to mitigation. In the 1960s, local conservationists fought a years-long battle to keep Buffalo Bayou, which runs through central Houston, natural. Flood Control wanted to “channelize” it, by replacing its lush banks with reinforced concrete. And when its executive director of nearly two decades retired last year, he derided the notion that native grasses could soak up floodwaters as “magic sponges in the prairie.”

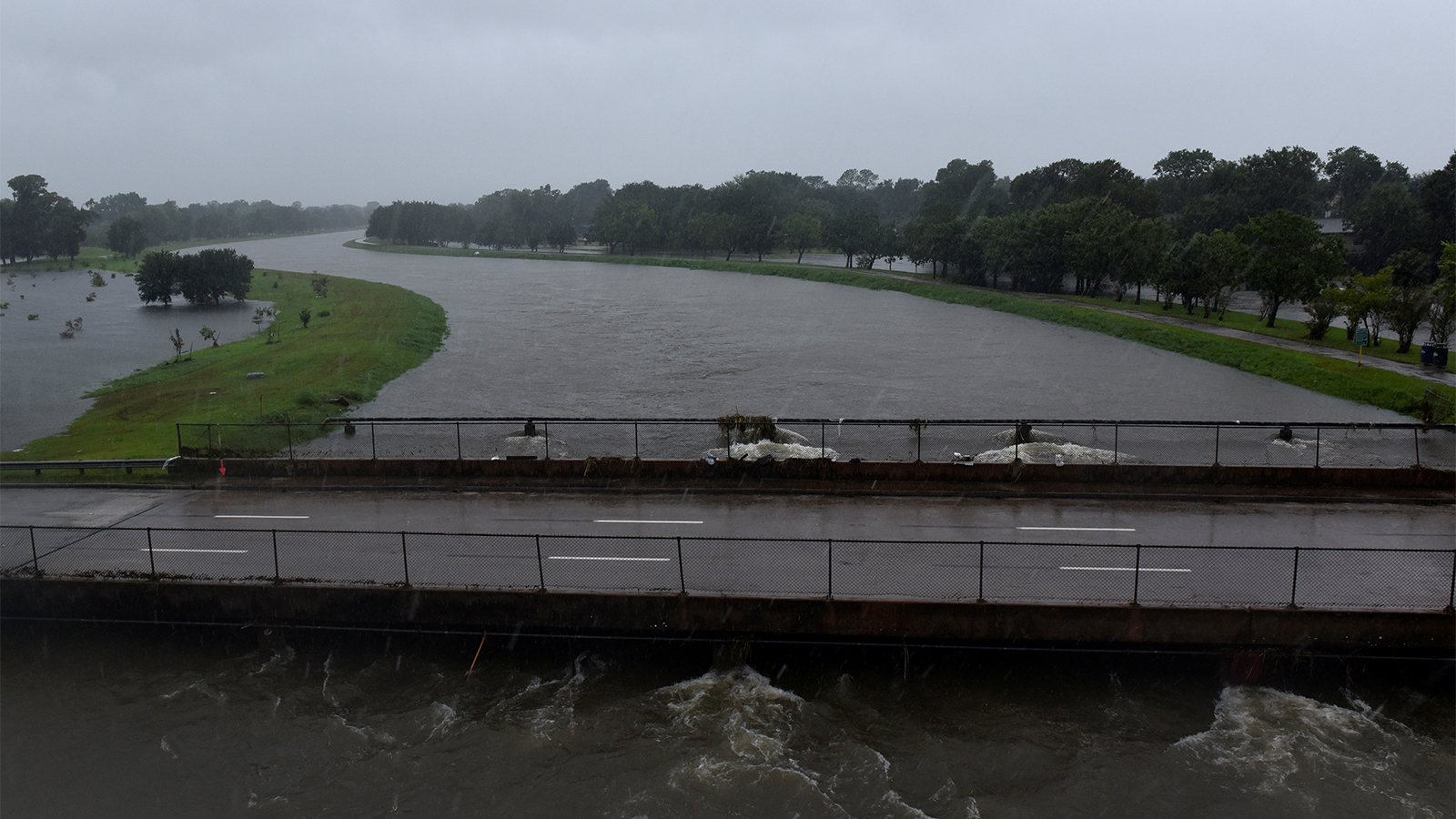

Brays Bayou overflows its banks in August during the rainstorm caused by Hurricane Harvey. REUTERS / Nick Oxford

Still, the district has increasingly turned to nature as inspiration for its flood-mitigation work. Steve Fitzgerald, chief engineer at Flood Control, tells me that by strengthening the main banks with plants and allowing a bayou to zig-zag, the agency is reducing the risk that the waterways will fill with silt and need to be dredged again and again.

“Bayous want to meander,” Fitzgerald says. “The more closely we emulate natural systems in our designs, the more likely the bayous will be stable.”

The results of this green-ward drift have been good for residents and wildlife alike. In northeast Houston, the Greens Bayou Wetlands Mitigation Bank, finished in 2016, filters water and provides habitats for native species. Flood Control planted trees along a river to prevent erosion and is using another creek to study how well prairies soak up floodwaters.

Bob Eury, executive director of the nonprofit Central Houston, attributes the greening of Houston and its bayous to a cultural shift that’s created strong public support for projects like Plan Downtown. Released earlier this year, it aims to create a “green loop” around downtown, in part by relying on the central stretches of bayou.

Eury, who jogs regularly on bayou trails, notes he’s seen a steady rise in the number of parkgoers. “Nothing delights me more than when I’m out running and I see a green heron flying up the bayou right through the heart of the city,” he says.

Back in Idylwood, the beautification hasn’t stopped all the flooding. The city has weathered three so-called “500-year” or “1,000-year” floods since 2015, including during Harvey — when parts of Houston got 52 inches of rain within days, more than the region normally gets in an entire year.

Jen Powis, who until recently was advocacy director for Parks Board, said the message of Harvey was that local government had failed Houstonians. “It was Harris County and Harris County Flood Control’s failure,” she says, adding that they had permitted “rampant development in areas they knew would flood.”

The hope is that with Greenways, there’s more of a buffer between Houston’s waterways and development — a fact Beth White illustrates by pointing to the trail we’re on along the Brays. It’s 10 feet wide, she says — to allow for Flood Control vehicles.

“We’re not primarily a flood-mitigation project,” she says. “But everything we do has to be looked at through the lens of flood mitigation.”

What Greenways is primarily, at least in White’s view, is an effort to get Houston’s residents to appreciate the natural beauty all around them — to make them care more deeply about where they live. She points to Amy Dinn, a member of the Idylwood Civic Club, as evidence of Parks Board’s success.

After Harvey, Dinn organized a group of neighbors to clean debris out of the bayous. She agrees that without the Greenways initiative making the waterways part of her neighborhood’s fabric, she probably wouldn’t have felt compelled to restore the waterways on her own time.

“That’s what got me up at 8 a.m. to clean it,” she says. “I wasn’t here for the coffee.”

*Correction: This piece originally stated that Houston Parks Board had acquired 5,000 acres of green space.