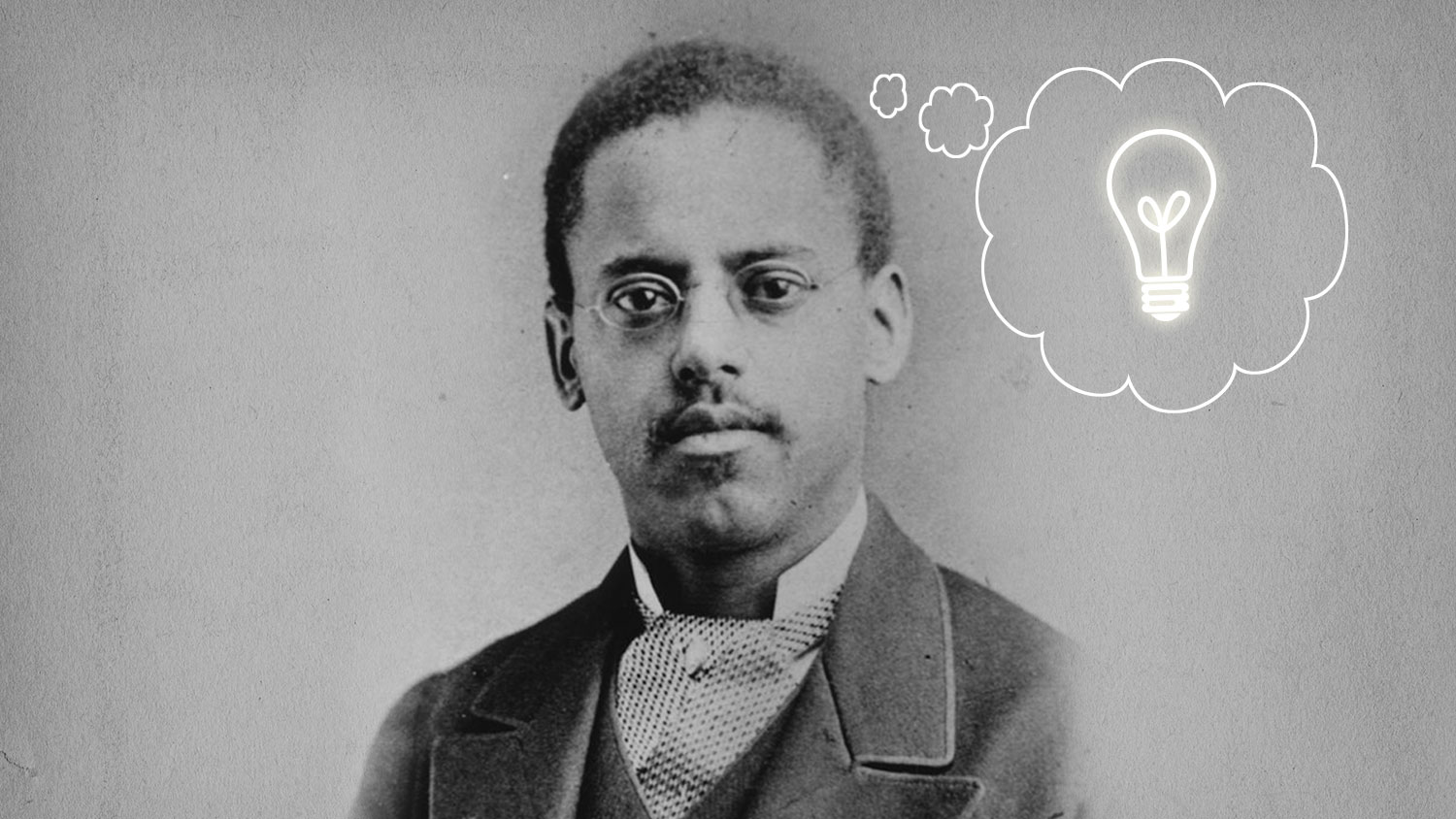

We’re interrupting your regularly scheduled programming on gentrification to bring you this Black History Month profile on Lewis H. Latimer, the African-American renaissance man who in the late 19th century helped not only invent the lightbulb, but also create the electric industry as we know it today. Yes, it’s common knowledge that Thomas Edison was the lightbulb’s inventor. And with today being Edison’s birthday, the electric industry won’t let us forget that, either:

It’s a bit generous to credit all of this to “one man’s vision.” There were competing visions all throughout the 1800s on how to efficiently distribute light, beyond a candle, and on how to power growing urban centers. Populations in northern American cities began exploding in the closing decades of the 19th century not only because of immigration from Europe but also because of migrating African Americans emancipated from slavery. Edison gets technical credit for patenting the first “practical incandescent” lightbulb during this time, and also, as the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) reminds us, creating the first electric light power station.

But while Edison got the patent on those, he got there with a lot of help from Latimer, who literally wrote the book on both. Latimer’s Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System is a bit more deferential to Edison than perhaps necessary. That was likely a reflection of the times when big ideas couldn’t possibly be ascribed to non-white people, especially when the burgeoning eugenics movement was considered serious science. But Latimer had already been involved in a major invention, having helped Alexander Graham Bell patent the telephone in 1876. In 1880, Latimer began working for the United States Electric Lighting Company, which was run by Edison’s rival Hiram S. Maxim.

A biography on EEI’s site states that while working for Maxim, “Latimer invented and patented a process for making carbon filaments for light bulbs,” and helped install broad-scale lighting systems for New York City, Philadelphia, Montreal, and London. Latimer holds the patents for the electric lamp, issued in 1881, and for the “process of manufacturing carbons” (the filament used in incandescent light bulbs), issued in 1882. It was roughly 1885 when he finally joined forces with Edison and began improving upon his boss’s invention.

Latimer had no formal training in science, but believed technology and innovation could help advance the plight of African Americans still reeling from slavery. That whole “STEM will save people of color!” cause is nothing new. The important thing, though, is that unlike peers like Booker T. Washington, he didn’t believe that simply learning a trade or two would be black people’s ticket to freedom. He understood how power worked structurally to disenfranchise and disempower black people, immigrants, and the poor in general. This is evidenced in both the prose and poetry he wrote during his time about electricity and society.

“The lamp embodied the relationship of art and science, and its improvement promised benefits for all classes of society,” wrote Bayla Singer, a professor at Rutgers University, in an article on Latimer and his work. “The electric light was a cause well worth serving. All of Latimer’s inventions, patented and unpatented, relate to improving the quality of life.”

His aforementioned book Incandescent Electric Lighting demonstrates an understanding of how the new technology could bring electricity to those who previously couldn’t afford it. On the electric lamp he wrote, “Like the light of the sun, it beautifies all things on which it shines, and is no less welcome in the palace than in the humblest home.”

And yet his book’s preface notes how this new industry he and Edison were creating was admittedly shifting society from one of independent or localized power to a more centralized version:

While these central [power] stations cheapen the production of the light, and bring it within the reach of those who otherwise could not afford it, it does away with the large number of isolated plants, which formerly afforded the curious an opportunity to inspect the generation, distribution and utilization in light, of this form of energy.

Today we are no longer confined to combusting coal to power our lighting and heating devices. We now have the technology to take that “light of the sun” Latimer wrote about to energize our endeavors. Not only that, but through rooftop solar power, we find ourselves arriving back at a place where “the curious” can generate and distribute their own energy, through net metering and similar enterprises.

EEI finds itself caught in the middle of these advances today, purporting to invite the kind of innovation praised by Latimer and Edison, but worried that the energy independence or energy democracy that comes with solar distributed generation will cut into electric utilities’ profits.

In a briefing today for Wall Street analysts, bankers, and investors, EEI executives acknowledged the spread of solar and other renewable energy sources, but assured everyone that the electric utility companies would remain at the forefront and continue to profit no matter what.

“A number of pending and proposed regulations will transform the way that electricity is generated, delivered, and consumed,” said EEI Vice President David Owens, who’s been co-opting black and Latino organizations in an effort to make rooftop solar more expensive. “The bottom line: Customers expect us to develop and sustain a grid that supports all of these needs, while giving them flexibility and choice in how they use energy. As the grid continues to transform, we need to make sure that it is managed with expertise and system know-how.”

Meaning, they will be making sure EEI’s expertise is managing those efforts, even as they approach headwinds from an energy democracy movement that no longer wants to be dependent on the centralized utility station system. Organizations like the Center for Social Inclusion, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, and Grid Alternatives are pushing solar distributed generation as a way to empower historically under-resourced communities and create wealth for them in the process. Because right now, the wealth from generating electricity is flowing to the monopolized utilities.

Richard McMahon, EEI’s vice president of energy supply and finance, told the Wall Street crowd today that investor-owned utilities posted a higher average return than the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 in 2014. “Over the longer term, electric utilities’ total returns have continued to reward investors more handsomely than the broader market,” he said.

More handsome profits means EEI gets to dole out perks to black and Latino groups to carry out their agenda, which the L.A. Times picked up on recently. Visitors of the lauded Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem might get a sense of this when they see that a gallery there named after Latimer is funded in part by the Consolidated Edison Company utility, an EEI member and one of the largest investor-owned utility companies in the nation. Though, to be fair, Consolidated Edison is one of the few investor-owned utilities that has pledged to discontinue building additional, unnecessary power stations and get out of the way of expanding local solar generation.

Still, we haven’t seen EEI and its members step outside their silos to show support for causes to improve the lives of people of color beyond their electric bills. Rather, we see them peddling resolutions that appear to be ghostwritten by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a group behind controversial policies like “stand your ground” laws, which have been blamed for the death of the unarmed, black teenager Trayvon Martin.

Latimer likely would’ve been disappointed in these stances and alliances. For all of his passion for scientific innovation, he didn’t neglect racial justice. In a letter he wrote in 1895 in support of the National Conference of Colored Men, a “My Brother’s Keeper”-like initiative for that time, Latimer wrote:

If our cause be made the common cause, and all our claims and demands be founded on justice and humanity, recognizing that we must wrong no man in winning our rights, I have faith to believe that the Nation will respond to our plea for equality before the law, security under the law, and an opportunity, by and through maintenance of the law, to enjoy with our fellow citizens of all races and complexions the blessings guaranteed us under the Constitution.

That’s what we’d call true enlightenment.