Do you build futuristic, low-friction transit pods that can operate in a transit system that hasn’t been built yet? How about one that may not ever exist?

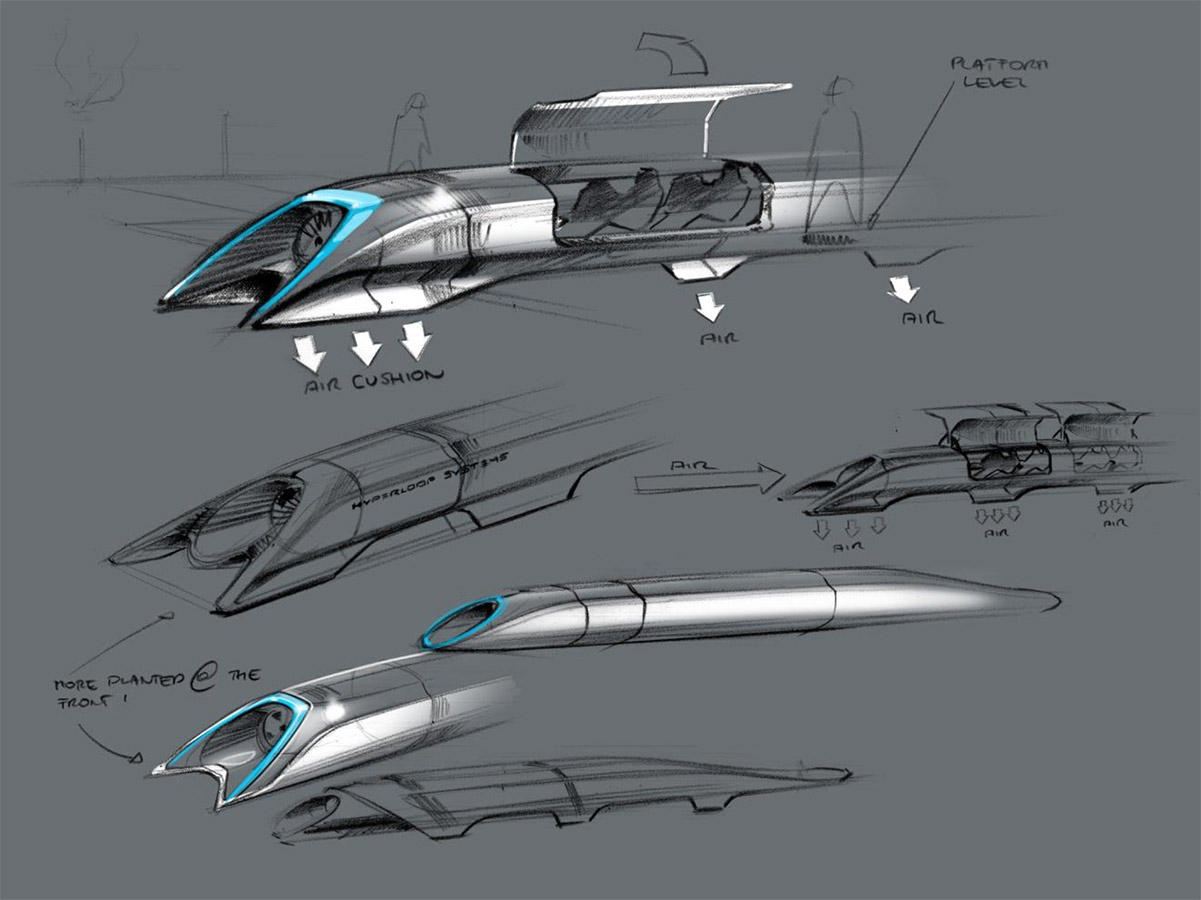

SpaceX, the aerospace manufacturer, is building a one-mile Hyperloop track adjacent to its headquarters in Hawthorne, Calif., so that on an as-yet-undetermined weekend next June, it can hold a race with experimental Hyperloop pods — sealed capsules that hold 28 people or 3 cars, and are propelled by magnets through Hyperloop tubes on a cushion of air, like a much, much faster version of a pneumatic tube system. The competition is open, though the entry form states a preference for “university students and independent engineering teams.” There appears to be no prize whatsoever, other than pure glory.

As a San Francisco resident, and a transit nerd, I have mixed feelings about this Hyperloop. SpaceX founder and solar panel/electric car magnate Elon Musk drew up the 58-page plan for it in 2013, partly in a fit of pique to show the world (but especially California) just how boring and non-futuristic modern transit has gotten.

At the time, I was enchanted by the sheer weirdness of the Hyperloop. I still am. It looks like something out of a sci-fi cartoon. Musk describes it as “a cross between a Concorde, a railgun, and an air hockey table” — three separate objects that I, for one, would very much like to see try to make babies with each other. It would be solar powered, and generate more power than it uses. It would be way cheaper than California’s high-speed rail project. It would get someone from San Francisco to Los Angeles in 30 minutes and for $20. It would leave every two minutes. A national Hyperloop network could make it easier to commute into a city in a whole other state than into a suburb of your own city. If the thing worked at all, that is.

After all, Musk made it clear that he didn’t want to build the Hyperloop himself, and he wasn’t even entirely sure how he would build it. He was just putting the idea out there so that someone else could build it, though he mentioned that he was “happy to work with the right partners” who shared the “philosophical goal of breakthrough tech done fast & w/o wasting money on BS.”

Since then, two years have passed. A crew of about 200 engineers began collaborating on plans for the Hyperloop online. A company called Hyperloop Transportation Technologies announced plans to build a five-mile track as part of an improbable-sounding housing development in the Quay Valley. Now Musk and SpaceX are holding this competition — though, they insist, they are still not building anyone a Hyperloop. Just a tiny one, for competition purposes.

In terms of feasibility the Hyperloop strikes this reporter as right up there with the Alameda-Weehawken Burrito Tunnel. In the meantime, while the bullet train languishes, and the Hyperloop pods race each other in Los Angeles County, what if California experimented with the forms of transit it already has between San Francisco and Los Angeles? The internet — and the ability to telecommute — has made speed of transit less important to a whole genre of workers.

What if, for example, someone revived the overnight trains, like the Lark and the Owl, that used to run between the two cities? The infrastructure’s already there (well, mostly — if you pretend that leaving from Emeryville is close enough to leaving from San Francisco). This reporter would ride one, especially if it had strong wireless and a way to bring my bicycle. In a better world, California could be as creative with the technology of its past as it is with the technology of its future.