Each night, the Qinghai-Tibet train leaves Beijing at 9:30. A mere 48 hours later, it rolls into Lhasa, 2,525 miles away.

Waiting to depart from Beijing.

Photos: Erica Gies

Shortly after 9 p.m. one warm night last fall, my travel companion and I raced through the sprawling West Beijing train station, weaving our way through a crush of humanity sitting on newspapers and bits of cardboard, eating cups of noodles while waiting for their own journeys. Winded, we boarded our soft sleeper car on Train 27 and made our way to our compartment — only to find it overflowing with Chinese passengers. As it was impossible for us to enter, we strained around them to peek in, and saw that they had strewn their belongings over all four beds and into every storage space.

We soon realized that only two were actually riding the train: a woman fresh out of ankle surgery with prominent staples in her bare, blue-black foot, and her daughter, host to a nasty respiratory infection that would become my partner’s and my new companion for the rest of the trip and beyond. The others were tearful relatives who could not bear to say goodbye until just before the train started rolling.

Passengers eye the scenery.

Photo: Michael McCrystal

Ever since the $4.2 billion railway began operating in July 2006, 4,000 passengers a day have taken advantage of the chance to visit — or work in — Tibet. It may be part of the same country, but it’s a world away to most people. While traveling in China, I had noticed an invariable reaction when I told people I planned to ride the train: A dreamy, almost nostalgic look crept into their eyes. “I want to go to Tibet,” they would say, with wistful longing. Maybe they appreciated Tibet’s heritage and its comparatively clean environment. Perhaps some yearned for economic opportunity. Now, thanks to the train, they can more easily and cheaply see the area firsthand — a development that is both a blessing and a curse.

Although I knew the new train was controversial in some circles due to cultural and environmental concerns, I wanted to ride it myself in an attempt to learn more about the gravity of those issues. For me, like so many people, Tibet had long loomed mythical as an isolated place where the culture has remained relatively pure. Rolling into it over a couple of days seemed preferable to dropping in suddenly via plane. One approaches what is mysterious by degrees.

Nearer My Sod to Thee

Once the relatives were on their unmerry way and our two suitemates realized they’d be seeing a lot of us over the next two days, they smiled, made space, and offered us heaps of packaged sausage, smoked fish, the ubiquitous cups of noodles, oranges, and my favorite, mahogany-colored nuts shaped like handlebar mustaches.

The train itself was clean and new, with bedside TVs in our $158 class (hard sleepers are six-person cabins for $102; $49 buys a hard seat) and large windows to appreciate the view. Although the carpet was showing signs of wear after two short months of operation and our car received little attention during the trip — leaving the bathrooms splashed with noodle soup, green tea remnants, and worse — the trip was generally smooth.

What, you’ve never used an oxygen outlet?

The railway, a great ambition of Chinese leaders since the “liberation” of Tibet in 1950, is a feat of engineering any country would crow about. It cruises the highest elevations of any track in the world, offering a chance to meditate on the sweeping, wildlife-dotted grasslands of the massive Tibetan Plateau, with an average elevation of more than 13,000 feet. It ambles through the rugged, 16,640-foot Tanggula Mountain Pass, forcing passengers who aren’t taking an altitude-sickness medication to grasp for the breathing tubes and oxygen distributed by train personnel, as bags of chips and toiletry bottles explode.

Altitude is not the only thing that makes this railway stand apart. Its construction and operation have been hailed by China as a model of environmental consciousness. Many in Tibet, however, fearful of the impacts of tourism and industry on their relatively pristine region, see it as just the opposite.

At a ceremony held at the Golmud, Qinghai, Railway Station to inaugurate the line, President Hu Jintao emphasized the importance of protecting the environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. He said railway workers and passengers should “consciously treasure waters and mountains as well as grass and woods on the plateau, and they should help conserve the ecosystem and environment along the railway.”

The majestic mountain view.

There’s plenty to conserve. The railway traverses two nature reserves and runs alongside several more. These parks are home to the endangered Tibetan antelope, gazelles, wild asses, black-necked cranes, snow leopards, white-lipped deer, Siberian tigers, blue sheep, and endemic plants. By most accounts the Chinese government did everything it could to mitigate the effect of construction on these species and their surroundings. A 2003 report by U.S. Embassy workers, for instance, relates a story of bosses halting work on the line for four days to ease antelope migration, even removing marker flags so their flapping wouldn’t scare the skittish beasts.

Today, China is so proud of the $192 million it spent on mitigation, including 33 wildlife migration corridors, that it touts these achievements in regular announcements in Chinese and English during the course of the train journey.

The government also boasts that engineers tackled the vexing problem of building on unstable permafrost by using solar energy to circulate liquid nitrogen and cold nitrogen gas through underground pipes, thus keeping the ground safely frozen. Workers are said to have removed virgin grassland sod from the right of way and tended it lovingly for a year before replanting it on the new line’s embankments. And the Chinese are so concerned with train-related garbage that they have installed special waste- and sewage-collecting devices within the train, and run a separate garbage train behind to pick up the trash from collection stations. The waste is then taken back to Golmud for treatment.

But all is not as green as it seems. Tibetan nomads tell tales of track being laid through the middle of fertile farmland and grazing land, destroying and damaging it, and claim the compensation they were paid was not enough to sustain the loss to their livelihoods. The solar-powered permafrost freeze hasn’t kept the land from shifting, and cracks have been reported in the concrete structures, railway ministry spokesperson Wang Yongping told the Beijing News. Embassy officials saw no evidence of rolling up or transplanting the turf. In fact, the report said because the native grass grows in clumps, this task would be nearly impossible, as would be reseeding. However, it did conclude that the swath of tundra disturbed by construction was quite narrow.

In spite of the railway’s best efforts, I did see a small trail of trash along the rails for much of the journey, which I ascribed to the workers, since the train was sealed due to the altitude. The embassy report highlighted this problem too, stating that there was considerable garbage, human waste, oil drums, and abandoned vehicles at shantytowns that sprung up along the work sites, a situation to which a local NGO called Greenriver has worked to draw attention.

As we skimmed along the tracks, I began thinking that the biggest problem facing this railroad may be beyond any one country’s control. Indeed, if global warming continues its current trajectory, according to a climatologist quoted in China Daily, the melting permafrost will prevent the railway from operating safely by 2050.

Next Stop, Lhasa

By most Tibetan and long-term expatriate accounts, it’s not the train per se that will have the most environmental or cultural impact. Rather, it’s what the train conveys.

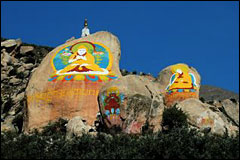

Painted rocks at Ganden Monastery.

Since July, the train has brought thousands of people into Lhasa’s Liwu station every day, most of them Han Chinese. When I detrained at the brand-new station after two days aboard, it was instantly clear to me that China has great plans for rail in Tibet. The station is immense — far bigger than is possibly required for current needs. It is architecturally grand in a way that makes a bold statement to a people who have spent centuries commuting behind their yaks.

In fact, the Chinese have already laid track beyond Lhasa. A source in town said a line to Sikkim, India, about 200 miles away, is already in place. Chinese TV has broadcast plans for the line to go to Xigaze (which Tibetans call Shigatse) within three years. There are further plans to lay track to Nyingchi and then to Dali within the decade, and also to connect Shigatse and Yadong, near the China-India border.

Even before the train went through, tourism to the Tibetan Plateau had swelled to 1.22 million in 2004, up from a mere 1,059 in 1980. In that year, 95 percent of visitors came from abroad. In 2004, 92 percent were domestic tourists, according to Phayul, a newspaper based in Nepal.

As the Chinese economy continues to grow, the middle class is expanding, allowing more citizens to travel for leisure. Until recently, it has been difficult to travel abroad. Tibet has proved a good alternative because it is one of the most exotic places in China and, as one person told me, there is a certain nostalgia for the simple life that many Tibetans still have — a life that many Chinese people had just 10 years ago.

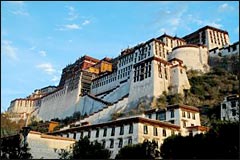

Potala Palace, a sign of the changing times.

My first morning in Lhasa, I got a clearer look at how things are changing in that city of 260,000 when I climbed the 13-story Potala Palace (once monastery, now museum, if that is any indication). While the Chinese census of 2000 says that Lhasa is 81.6 percent Tibetan, Tibetans estimate the demographics are closer to 50-50. From the palace’s top floors, I could see that the city is neatly divided into the new section of town, which looks like any other modern Chinese city, and the old Tibetan part of town, which appeared to be on fire, so vast were the great wafts of smoke rising from incense pots burning juniper throughout the public squares and temples.

Throughout the region, Chinese flags fly from Buddhist temples, and armed police add ominous undertones to houses of worship. Locals say the new 13-story police station in Lhasa was built to rival the Potala Palace. It is illegal for anyone, including tourists, to carry a photo of the Dalai Lama. Tibet is a place where people are afraid to speak on many subjects unless they know they are completely alone with their listener.

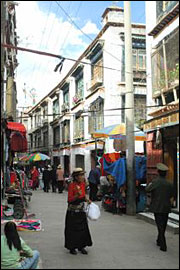

Detail of Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple.

Still, because Chinese influence has been minimal in areas of Tibet away from roads and rails, the culture has remained largely intact. Religion imbues life everywhere you look. One rainy morning, I awoke to the sound of chanting monks twirling prayer wheels outside my hotel window on one of the twisted, cobbled streets of old Lhasa. Colorful prayer flags said to represent sky, water, fire, wind, and earth adorned bridges and mountains.

As the flags’ symbolism indicates, Tibetan Buddhism has a holy reverence for nature derived from its roots in the area’s original animist and shamanist Bon religion. The Tibetan government in exile — holed up in Dharamsala, India — explains that Tibetans have been good stewards of the environment because they believe all living beings are sacred.

“Tibetan Buddhist scriptures explain that the Earth is the noe (container) and all the things on this Earth — biotic and abiotic elements — [are] the chue (contents),” writes Tsultrim Palden Dekhang on the government-in-exile’s website. “Thus if the container is broken and destroyed, it cannot contain the contents; similarly is the case with our Mother Earth, which is the container sustaining the lives of countless living creatures including the lives of human beings.”

A woman with a prayer wheel eyes a police officer in an alley of old Lhasa.

Chinese officials do seem to recognize that many tourists, Western and Han Chinese alike, come to Tibet for both the culture and the unspoiled environment. They have, for instance, set aside one-third of the Tibet Autonomous Region — an ostensibly self-ruled area that encompasses the entire Chinese province of Tibet but only about half of historical Tibet — as parks. And Tibet is valued as the principle source of 10 of Asia’s legendary rivers, including the Yangtze, Yellow, and Mekong, which supply billions of people with water, energy, and food. The government of Tibet in exile estimates these rivers sustain the lives of 47 percent of the world’s, and 85 percent of Asia’s, population.

Still, many — including the group Greenriver — worry about the environmental impact of the immense swell in tourism, and the role of the train in further increasing that. Adding to the concern, there is some question as to whether protections currently in place will stand when opportunity for profit presents itself. Tibetans and expatriates alike fear that Chinese officials have set their sights on Tibet’s mineral resources, which include coal, iron, jade, and copper — plenty of things worth digging for.

A Land of Riches

From 1995 to 2004, China grew at an average of 9.1 percent annually, according to the World Bank. By comparison, the U.S. economy averaged 3.3 percent annual growth during the same period. Every year, 13 million people — equivalent to the populations of New York, L.A., and Dallas combined — move from the countryside to China’s already packed cities, leaving behind lives of subsistence agriculture to join the global industrial economy. The country currently gets 75 percent of its energy from coal, but to continue feeding this phenomenal growth, it is strategically looking to increase its access to every type of energy source: coal, oil, natural gas, and renewables.

And Tibet may hold at least part of the solution.

One geographic survey on the Tibetan Plateau found the area rich in oil resources, with potential reserves estimated at more than 10 billion tons, Zhang Hongtao, deputy director of the China Geological Survey Bureau, told the Xinhua News Agency in December 2005. For a country that some predict will be consuming 330 million to 350 million tons of oil by 2010, that could prove irresistible. The survey also found large iron-rich ore deposits, with a potential reserve of more than 50 million tons each, and the news agency Interfax-China estimates that the TAR could be the largest mineral resource in the country, with a potential value of more than $128 billion. All told, the region holds more than 100 minerals at more than 2,000 potential mining sites. Less than 1 percent of discovered mines have been prospected thus far.

So why aren’t Chinese companies extracting already? They are, to a point, but people I spoke with in Tibet said the infrastructure is still not really adequate for large-scale projects. The train is one step to exporting materials back to China’s big cities, but Tibet is vast — more than twice the size of Texas — and the minerals are frequently in obscure locales. More rail and roads would need to be built before Tibet would look like the rest of China. Still, the new rail lines and the web planned across the region are seen as critical steps to opening up Tibet’s virgin territory to China’s industrial might.

Tenzin Choephel, a reporter for Phayul, interviewed some recent Tibetan refugees — newly free to speak their minds — to get their opinions about the train. “Large numbers of poor Chinese would come to Tibet and the railway would transport mineral ores from different parts of Tibet even though the government says it is for carrying passengers,” said Yeshi Damdul from Tölung Dechen County.

Tsering Dhondhup from Damshung County said, “Locals don’t have any right to say anything and no one dares to speak, they blast lots of dynamite and it was harmful to people because it destroyed nomadic grasslands.” Dhondhup continued, “Mining is done beyond limit and it would continue in the future also because the railway track is also purposely made near mining areas … when the railway comes, many Chinese would come and we would lose all our land.”

While environmental protection reportedly accounts for more than 30 percent of the total cost of Chinese mining projects in Tibet, a higher level than in other regions of the country, it may not be enough. And China’s not the only country with an eye on Tibet’s riches. Western companies have also begun exploration and have acquired rights to sites, sparking protests from activists and an appeal to reconsider from the Dalai Lama himself.

Witness to Change

While Tibetans do what little they can to protect their land and traditions, the new Han Chinese Communist Party Secretary of the TAR, Zhang Qingli — who has a reputation as a hardliner — is running a “patriotic education campaign” that was first implemented in monasteries but is being expanded to the general public. It forces Tibetans to agree that Tibet is historically part of China and to denounce the Dalai Lama, among other key points. Resentment expressed by monks and nuns has resulted in detentions, expulsions, and an apparent suicide, according to the U.S. Congressional Executive Commission on China. “Those who do not love their country are not qualified to be human beings,” Zhang said in an interview with Der Spiegel.

But by definition, Tibetans’ necessarily subtle rebellion and whole-being expression of their culture is fundamentally human — and poignant.

One night during my visit I stumbled into a neighborhood restaurant in Lhasa. As I was the only non-Tibetan there, those inside looked up, surprised. But then everyone smiled warmly and the proprietor served me spicy tsampa soup — noodles made of barley, the only grain that will grow at 14,000 feet. As I began slurping and wiping my nose, the locals went back to laughing, drinking (occasionally raising a glass to me), and cheering and jeering a TV program I can only characterize as “Tibetan Idol.”

Pilgrims stroll the Barkhor.

The next day, I climbed to the roof of the Jokhang Temple, the holiest site in Tibetan Buddhism, situated in the center of an area known as the Barkhor. My rooftop perch offered some perspective on the endless merry-go-round of pilgrims, tourists, and supplicants circumambulating the temple clockwise, as required by custom.

Across the big square fronting the temple, I saw five Chinese police chasing a small posse of Tibetans through the crowd. Down an alley, a group of Khampas — hardy cowboys from eastern Tibet with long, braided hair wound around their heads and studded with large, mock turquoise and coral stones — crowded around a dealer in metal horse gear, seeming worlds away from thoughts of the new iron horse in their land. Nomadic pilgrims took a break from their prostrations to sit at the foot of an immense incense pot, snacking upon dried yak. And beyond the color and chaos and noise and scents and beyond the pole strung with prayer flags, the mountains leaned against the confrontationally blue sky, witness to Tibet’s past, present, and future.