Stuck at a standstill between blaring horns on a stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway through Long Beach, Calif., my 9-year-old self felt pretty sure our car was about to get swept away by the torrent of water pouring from the sky. “Mom, what’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s El Niño,” she growled.

Whoever this El Niño was, I could tell that should he and my mom ever meet face to face, it’d be best to get out of their way.

Many people who lived in California between December 1997 and May 1998 probably had similar feelings. It rained nearly continuously for the whole of February. Precipitation records were set in at least 19 stations in the state that month; Santa Barbara smashed its old high by 4.41 inches. Widespread flooding and mudslides did at least $550 million worth of damage statewide.

The first two months of 1998 were the warmest and wettest the contiguous U.S. had ever seen for that period. The whole country averaged 5.4 degrees F above normal. El Niño was blamed for floods in the Southeast, a huge ice storm in the Northeast, and tornadoes in Florida. Globally, it caused 2,100 deaths at a least $33 billion in property damage.

Well, brace yourselves: Word on the street is that the kid has spent the last 16 years gathering up his gusto – and he’ll soon be back in town. There’s even some whisperings that he’s already here.

El Niño, which means “the boy” in Spanish (as in Jesus – because its effects are most strongly felt in South America around Christmas), is a phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) when things heat up over the tropical Pacific Ocean. To understand why this happens, see the video above. But perhaps what’s more important to hash out is what it means — which, if it’s a big one, is global meteorological disruption. If a big El Niño comes to town, we could see Peru’s fisheries collapse, India totally parched, and flash floods, wildfires, mudslides, and record high temperatures stateside.

Could is the operative word in all of this. While European scientists now say there is a 90 percent chance of an El Niño forming this year (if it hasn’t indeed formed already), what, exactly, an El Niño will do depends a lot on its particular strength. We can even see this by looking at the last few years: There have been a couple of El Niños since the one in 1997-’98, most recently in the winter of 2009-’10, but they were perhaps less memorable (though, depending on where you look, still pretty serious) because a strong El Niño plays out so differently than a weak or moderate one. For example, while a strong El Niño brings on the deluge, Los Angeles is actually a little more likely to be unusually dry than wet during a weak El Niño.

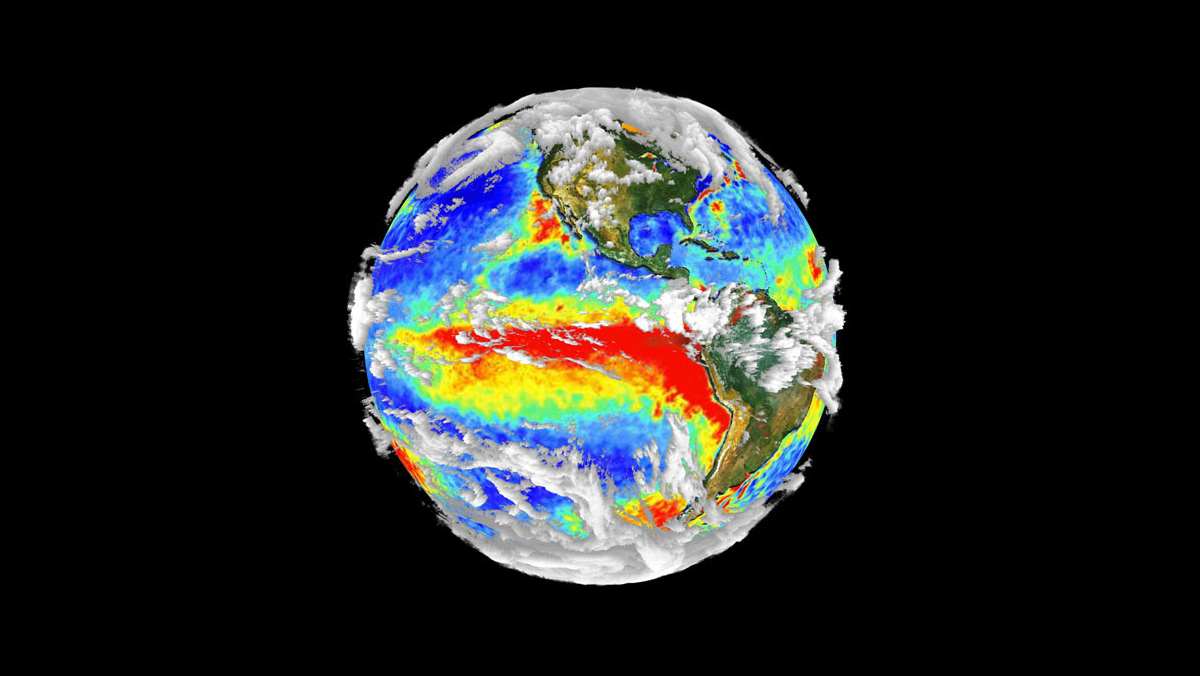

NOAASea surface temperature during an El Niño event.

So, what is going to happen this year? Well, a few months ago meteorologists began to take note of sea surface height conditions (measured via satellite) that were strikingly similar to what we saw in the months preceding the two last big El Niños (1997-’98 and 1982-’83). This led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to issue an official El Niño watch in early March. Since then, those conditions don’t seem to have gone away – and so the likelihood of El Niño forming continues to rise. At the same time, the rapid warming scientists saw a few months ago has now leveled off, meaning that it’s looking less likely that it will be another monster.

But we won’t know for sure what we’re in for until the trade winds start to shift, which is what’s needed to trigger the event (again, see video above). For a big El Niño, we’ve got to have both the oceanic conditions in place (which is what scientists began to take note of in March) AND the atmospheric ones. As of now, the trade winds haven’t consistently weakened, which is a big part of why we still don’t know how this is going to play out.

But whether the boy is coming this year or not, we haven’t seen the last of him. Scientists believe that the so-called “global warming pause” we’ve seen in the past 16 years is the result of the Pacific Ocean spewing out so much of its heat during the El Niño of 1997-’98. Since then, it has had more of an appetite to suck atmospheric heat back in — and because the trade winds haven’t slackened much since then, the Pacific has held on to all that warmth. So, when a big El Niño does form again, us landlubbers are going to heat up … really fast.

On the positive side, that could help convince more people that this whole climate change thing is real. And a little rain would be welcome in drought-stricken California. But there will be many, many downsides — and not just especially bad traffic jams.