Al Gore tried to invoke the moral imperative for climate action. “It’s not about right and left;” he said, “it’s about right and wrong.” Climate deniers cynically pounced on Gore’s leadership as an opportunity to assert the exact opposite.

(Really, it’s about both, but we’ll get to that later. See footnote if you can’t wait.)

Why don’t Americans accept the climate challenge as a moral imperative? University of Oregon researchers Ezra Markowitz and Azim Shariff tackle the question in Nature Climate Change. Markowitz blogs their conclusions here.

Their analysis draws insights from broader research on “the moral judgement system – the set of cognitive, emotional, social, and motivational mechanisms responsible for producing our perceptions of right and wrong.” They describe why our moral discriminators have a hard time grokking climate disruption, and offer potential strategies for activating moral intuition. It’s interesting stuff, worth a look. Their blog post is a good summary; I’ll just poke at couple of themes that seem to need poking.

The Guilt Trip – Climate disruption is like my (dear) Jewish mother; it makes people (and especially Americans, say the authors), feel guilty. From the Nature Climate Change paper: “To allay negative recriminations, individuals often engage in biased cognitive processes to minimize perceptions of their own complicity.” From my adolescence: “I can’t hear you Mom!”

This makes sense (we are guilty!), but it downplays the importance of efficacy in the development of moral responsibility. Bob Doppelt makes the case that motivating big changes in human behavior requires dissonance, efficacy, and benefits. Lack of efficacy often seems like the bottleneck when it comes to moral engagement on climate. The strategies within any actor’s scope of effectiveness are not scaled to the problem. No use accepting guilt, let alone responsibility, if you can’t do anything about it. “May I be granted serenity…,” etc. Moral intuition finds no traction where there is no efficacy. (This is why we do what we do at Climate Solutions.)

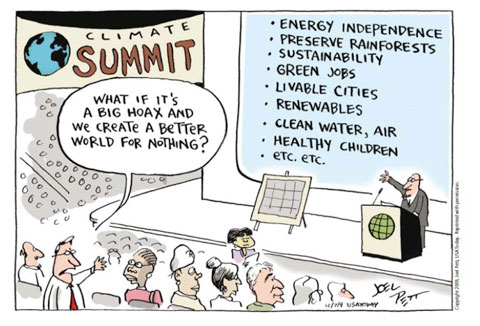

The Co-benefit Conundrum – This cartoon is a staple of climate advocacy:

To build support for climate solutions, we focus on “co-benefits” – often going so far as to shun discussion of climate altogether (which, as I’ve harangued, is a big strategic mistake.) There’s no denying the effectiveness of this approach in building bridges to new constituencies for action. Air quality, economic opportunity, and transportation choices are intuitively positive, accessible, tractable. Stabilizing atmospheric concentrations of GHGs is not, not, not.

But the focus on co-benefits can have a perverse effect on moral intuition – like saying “Do this because it will feel good.” The pitch allows us to infer that we don’t need to do it unless it feels good. Or if some other thing feels better, we can just do that instead. It’s morally disengaging.

In a classic of motivational speech, Winston Churchill said, as he was rallying the Brits to war with Germany, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” It is the stark and pointed absence of co-benefits that underscores the necessity for action and makes the rap so powerful.

Hmmm. Big climate advocacy problem: Either we a) keep pumping co-benefits, even at the expense of suppressing moral intuition, because it’s an effective way to build a broader political constituency for climate solutions, or b) downplay co-benefits and just bum folks all the way out, to make the moral imperative as naked and absolute as it must be to drive climate action at scale (the Churchill approach).

Both these options suck. I’m no Churchill, and climate disruption seems to lack the fear-focusing power (though certainly not the destructive potential) of the Third Reich. So I’ll keep selling co-benefits, while taking every opportunity to press the case that climate action is a moral imperative, not an amenity. But I won’t try to reconcile this tension with handwaving about “balance” between moral urgency and marketing co-benefits, at least not today. For now, let’s just leave it hanging out there as the conundrum it is.

Footnote: Naomi Klein makes the case that it IS about right and left, but only the right gets that. Radical conservatives view climate change as the ultimate Trojan Horse and organizing principle for progressive ideology. Progressives don’t think about it that way at all. It’s the right, Klein argues, who got the memo: the only way to seriously tackle climate disruption would be with a broad, sweeping societal mobilization, built on a foundation of progressive values and ambitious government action. The right can’t have that, and the left isn’t really pushing for it.