All futures wind up in the dump. In that sense, artist Jenny Odell’s Bureau of Suspended Objects project — which explores the fuzzy line between art object and junk — fit right in at Fusion’s Real Future Fair in San Francisco, where I first heard about it. As you might expect from the event’s name, there was a lot of future on display — future food, future therapists, future dildos. Odell’s work focused on the far end of the futurism paradigm, where today’s futures land on the trash heap.

Pictured above is the public disposal area of San Francisco trash collector Recology’s dump — which is to say that it’s not the place that the city dump trucks go to, but the place where people come to pay the dump to take stuff off their hands. Odell was given an empty shopping cart and license to take anything she wanted from this room, as long as she stayed away from the giant claw that was pulverizing stuff. Her project was part of an artists’ residency that Recology has been doing for the last 25 years.

When Odell first arrived at the dump, her studio was empty. She pulled things from the pile until she had the makings of an office: A desk. A chair. A few fake office plants.

Then she got down to business. She took the empty shopping cart out again and began looking through the dump. When she found an object she was curious about, she investigated it like a detective and recorded her findings. Where had it been designed? Where was the factory that made it? How excited were people about it when it came out? How far had it traveled from the place where it was made to this spot, a municipal dump in San Francisco?

Odell has a history of doing this kind of research-as-art. In an earlier project, Where Almost Everything I Used, Wore, Ate, or Bought on Monday, April 1, 2013 (That Had a Label) Was Manufactured, to the Best of My Knowledge, Odell did exactly what the title says. She couldn’t trace everything back, but she got close enough to experience what she describes as:

… the alienation that occurs when one realizes that all of his or her possessions were not only made by strangers far away, but are still afloat and available in the marketplace — e.g. that an old teapot you’ve had for years has brand-new shiny cousins waiting to be ordered online, or that a wooden dolphin you bought at a flea market in a far away city (your most prized possession) is still being made by Chinese factory workers who also make wooden snakes, wooden sharks, and wooden pigs.

For Suspended Objects, Odell researched the stories of many, many objects (the full dossier is here) — but it’s the technological goods that most fascinated me. A lot of them aged hard and fast. People who visited the Bureau could use an augmented reality app on some of the objects to see how they had looked when they were fresh and new and exciting.

Many of the items in the Bureau’s tech collection are things that I had forgotten ever existed.

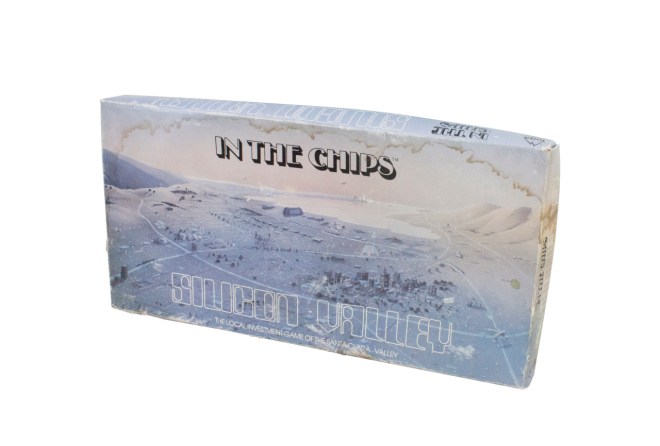

And I’d never even heard of this Silicon Valley board game. Its designers intended it to be “bigger than Monopoly”; today, it serves mostly as an object lesson in just how recently Silicon Valley as we know it emerged.

Because the game was made in 1980, several of the figures may seem jarring — for instance, a $35,000 salary at HP or a $280,000 house in Saratoga. Much of this can be attributed to inflation, but the game also ironically captures a simpler time in Silicon Valley — when the hype was just getting off the ground. It’s telling, for instance, that the opportunity cards don’t reference anything like startups but instead invite one to start bookstores and dry cleaning businesses, and that money is gained by winning radio contests, collecting insurance money on an injury, and renting your Lake Tahoe cabin. The car models are pedestrian and the most luxe-sounding square on the board is “purchase hot tub — $2,000.” Perhaps what this game most accurately portrays, then, is the pre-Silicon-Valley Silicon Valley.

As someone who spends a lot of time thinking about what our culture chooses to make and to discard, I needed to know more. Odell sat down with me recently to talk about what it means to investigate the origins of what America throws away.

Q. How did you trace these objects back? Did it take a lot of detective work?

A. I would just start with the physical object. I had this little pedestal right next to my computer. Whatever was currently being researched was on this box. I would examine it for numbers — if you get really lucky, old electronics from the ’70s will sometimes have the name of the factory on them. For whatever reason, companies were more OK with that — that these things were being made in Japan and being rebranded and then sold here. That was the best case scenario. What was more common was just a company name, maybe an FCC ID.

I read a lot of corporate histories. For example, Nintendo in the ’80s and ’90s had three factories, but the NES [Nintendo Entertainment System] that I found was made in a year when only one of those existed. So I could narrow it down to that specific factory.

Q. Is a corporate history interesting to read?

A. It’s interesting if you’re monomaniacally fascinated with finding out where something is from. When you have that filter, everything becomes interesting. I would get tunnel vision. Anything that would get me a bit closer to that — I would be at my desk at midnight at the dump.

Q. Is there anything in particular that you saw a lot of in the e-waste bins?

A. I saw a lot of things from the ’80s and ’90s. Gaming systems. Gaming accessories. VCRs. I don’t know the circumstances that led to their being thrown out. Especially since they still work. Sometimes someone is in a hurry. Sometimes people are just missing the adapter. Sometimes a company goes out of business.

Q. If you go to an antique store, most of it is “collectibles” — things you would put on a shelf and admire. But if you go looking for old pots and pans, you hardly find anything. Is some stuff so practical that it doesn’t get thrown away?

A. You would be able to find those so fast at the dump. Before I even got there, the other artist in my studio had found a cast iron pan, a hot plate. I found silverware, a cutting board, cups, knives, really quickly.

Q. Did it smell bad at the dump?

A. There’s a smell inside the pile, but not in the studio. And the smell in the pile is not rancid garbage smell. It’s definitely a smell, but I have really positive emotions associated with it. To me, it’s the smell of possibility. You go in there with an empty shopping cart, and go out with a heaping one.

Q. Did you find anything in the pile that you had longed for passionately as a kid?

A. Yes. The NES. I wasn’t allowed to have one. I never got to play it. I would go over to friends’ houses and they never wanted to play it because they were bored with it.

I got a big stack of games. I always wanted to play Super Mario. It plays fine except that the sky is purple and there are some glitch green bars that come up that are not supposed to be a part of the game, but are a part of the game as I am playing it now.

I was overjoyed that I could play this game for as long as I wanted. Forever. I still have it in my room.

Another one of the games is Rad Racer. When you play it there is no music, so you’re just driving through this existential desert. And when you get to the finish line, it just cuts to this glitch screen where this car is floating in the center of the sky. And then you start over. So you can never win.

Q. What was the ratio of stuff made in the U.S. vs. stuff made overseas?

A. The electronics were definitely from the ’80s and ’90s, but the stuff in the pile — there was a lot of ’40s through ’70s. Until the ’70s, most stuff was made in the U.S. That’s another thing that I abstractly understood that I now have a concrete sense of — the death of American manufacturing. In researching a factory, I would often come across an article about that factory closing, and then an article about the condos that are currently in that building.

Q. I feel like this is especially poignant in the Bay Area, where so many of us live in small spaces. We don’t have the luxury of holding on to too many objects. Have you heard about that The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up book?

A. No.

Q. I see it a lot in bookstores right now. The woman who wrote it insists that you have to go through everything in your house, hold it up in front of your face and say “Does this give me joy?” If it doesn’t — you have to get rid of it.

A. That is the exact opposite of the way that I think about objects. Mine is “hold it up in front of your face and realize that you’ve never looked at it before and realize that it was injection molded and came through this port in China and it is actually a mystical object.” I don’t care if it gives me joy. It’s a mystical object. It is what it is.

Part of the irony of the phrase “suspended objects” is that it’s supposed to mean that I suspended them from their trajectory. But in reality all objects are currently suspended wherever they are.

Another phrase I use is “imminent trash.” People who have things in their garages for 10 years are not interested in owning that object — but also not interested in going through the effort of getting rid of it. That object is psychologically trash already. Loading it into a truck and taking it to the dump is just moving it. So I am really interested in these orphan objects that are in transition. Stuck in this garage purgatory.

I don’t need to see things through a lens of usefulness or efficiency or happiness. All objects are almost paralyzingly interesting now. It can be very distracting. Everything recedes infinitely outward. But it is a more interesting way of being in the world.

Q. So what’s next?

A. I Just applied for a residency on a container ship. If I get it, I wanted to bring some of my objects with me to Shenzhen, the port they came out of.

I’m doing a second phase of the project this summer as an artist in residence at the Palo Alto Art Center. In that one, I’m asking people to bring me objects. It’s a trade — you tell me the story of your object as it played out in your life, and in return I will give you the story of the object when it was manufactured up until the point where you acquired it.

And only after that exchange has occurred will I get rid of the object. So it’s ongoing.

Q. This is a very inelegant way to phrase this … but do you feel like you understand trash in a way that you didn’t before?

A. What I have is — I have more of an appreciation for the stubborn materiality of trash. It doesn’t want to go away. It exists in the world. It’s made out of stuff. It’s not going to evaporate.

Everyone abstractly understands that trash doesn’t go away. But just watching day after day this front loader trying to smash the trash into oblivion and you hear and see the resistance of it. Pushing back. You can compress trash and move it somewhere else, but it is going to be there forever.

Like the part of the archive that I had to give away — that’s just somewhere else now. I don’t have access to it. But it’s still there.

I don’t know what trash is anymore. I don’t know what that category means. When I was in there [the Recology site], if I picked something off the ground and put it in my cart, that meant that it was no longer trash. And in the same hour, if I put it down, then it was trash again. When I go to the store, it looks like trash, and when I go to the dump, I feel like I’m shopping. I think trash is a psychological category.

Q. Where did the objects in the Bureau end up?

A. My original idea was that I wasn’t going to keep anything, but I had to, because some of it is going to exhibitions. It’s being divided up. Some of it is going to the Jewish Museum. Some of it is going to a gallery in Massachusetts. And some of it is going to a project my friend is doing called “The Museum of Capitalism.” I gave them a permanent loan from the Bureau of all the money-related objects: Money-patterned wrapping paper. A credit card swiper that went through a fire. Tony Robbins’ Unleash the Financial Genius Within cassette tapes, still in their wrapping.

Some of it I use. The salad bowl in my kitchen is from the dump.

I actually have to go back to the dump this week to archive more objects, because I committed to several exhibitions and realized I don’t have enough trash to go around. I have to expand my archive.