Aging infrastructure + warming climate = rising prices. That’s the basic conclusion of a new report showing that clean water is getting more expensive in cities across the country — in some cases, far more expensive than what poor residents can reasonably afford for what should be a basic human right.

Rates vary hugely across the country — water will cost you five times as much in Seattle as in Salt Lake City, for example — but on average, the cost of clean water and wastewater services has risen 41 percent over the last five years, according to an examination of national data by the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, a human rights advocacy organization.

In general, researchers say water should cost less than 3 percent of a family’s pre-tax income. But in several cities that the organization looked at, average residents are paying much more: 8 percent in Baltimore for families living at the poverty line, for example, and 7 percent in Detroit.

The fundamental problem: Municipalities treat water as a pay-as-you-go product, rather than a public good supported through tax revenue, such as police or public schools. But water is not a luxury. It’s a necessity. You can’t just stop drinking or bathing if you lose your job. And yet failure to pay the water bill comes with real consequences: More than 33,000 Detroit water accounts were cut off in 2014, for example.

The new report blames rising water costs on a variety of factors, including:

- Pollution from industry, agriculture, and fossil fuel production, requiring more communities to clean and treat their drinking water. Climate change, by increasing salinity and algal blooms, makes the problem worse.

- Population growth and drought in the arid Southwest and elsewhere (the new normal due to climate change), which means water is traveling farther to reach consumers, increasing costs accordingly. Drought surcharges can bring a family’s bill above $300 per month in some places.

- Increased rainfall from climate change in the East and Midwest, which causes flooding and fills water systems with pollution. Detroit struggles with overflowing sewers during heavy rainfalls, while New York City has to discharge sewage into its harbor after a storm. These situations can require costly upgrades to wastewater treatment facilities.

Not all experts agree about the extent of the problem identified in the service committee’s report — or the solutions. In 2014, the U.S. Conference of Mayors lamented similarly dire findings, which the group reiterated at an April Senate hearing. But Ed Osann, a water analyst at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, says in a critique that the conference’s analysis might overstate the burden on low-income residents, because their bills might be lower than the average, which is driven up by the wealthy using a lot of water for nonessentials like lawns or pools. Also, many poor people are renters who don’t pay for some utilities directly and programs to help poor people pay their water bills can also reduce their burden.

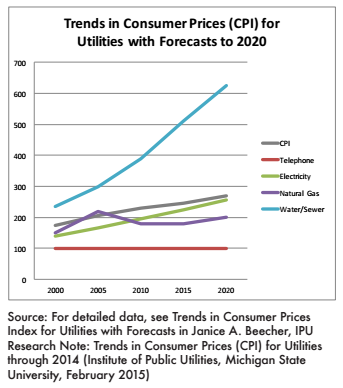

Osann doesn’t conclude that there is no water affordability problem, only that more precise data is needed. “Water and wastewater rates have been going up at twice the rate of inflation for a good 15 years,” he tells Grist. “So it’s become a significant utility bill, and it’s looming larger in family budgets.”

Better data about the impact of water costs on poor communities is something the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee would like to see, as well, but the group says its report relies on the best information currently available. And although advocates might not always agree on the exact details, they share a concern for access to clean water in low-income communities.

As with all environmental injustices, this one falls especially hard on non-whites. “Today, one in every two African-American Michiganers live in cities that violate their human rights to water and sanitation,” the service committee reports. Detroit and Flint, whose water problems have made national news over the past year, have majority black populations, as does Lowndes County, Ala., which has no functioning sewer system.

Even the United Nations has been critical of the U.S. record on water. In 2011, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation recommended that the United States “adopt a mandatory federal standard on affordability for water and sanitation,” which would require municipalities to provide clean water and wastewater services at a basic affordability threshold (such as 3 percent of household income). Congress, you’ll be shocked to hear, has done nothing whatsoever with that recommendation.

Because the causes of rising costs are real, making water affordable may be difficult. But it shouldn’t be impossible. The service committee offers several solutions, including prohibiting water shutoffs for nonpayment by low-income households or those with sick, pregnant, or nursing family members. The group also recommends requiring water utilities to charge less than 2.5 percent of each family’s income.

The committee also calls for adopting water access as a human right in federal law, which would force local governments to create water access for the homeless at clinics or other public facilities. (There are more than 500,000 homeless Americans, and most of them lack reliable access to clean water and sanitation.) Again, Congress has failed to even consider such action — although a new coalition of environmental justice groups plans to push for federal policy along those lines.

States and municipalities actually have much greater control over water delivery, however, so some advocates, like NRDC’s Osann, argue that it’s better to concentrate efforts there. He suggests that water utilities should adopt policies (already used in some places) that charge more for usage during peak summer months and above a certain threshold, since anyone using more than a certain amount of water is likely watering lawns with it, not drinking or bathing. This would shift the cost burden toward the wealthy, who can better afford it, and encourage conservation.