When we talk about gentrification, it’s usually in terms of comical caricatures: white hipsters jogging around with Otterhounds, then later found chugging on exotic microbrews in front of a pop-up performance gallery. We assume images of invasive, pale-skin denizens of a transitioning urban neighborhood that was once lived in almost exclusively by black and brown people.

But unlike in, say, Brooklyn, the Chicago story isn’t really about new mayonnaise shops and dog parks. While Grist writer Brentin Mock reports how gentrification is a real thing, especially in D.C. where he resides, the starker problem in Chicago is black neighborhoods that have suffered economically through the decades and are continuing to suffer.

At WBEZ, a Chicago public radio station, our neighborhood bureau reporters produced a package of stories, “There Goes the Neighborhood” (found here) in December, about the changing conditions of neighborhoods in racially segregated Chicago. We partnered with the University of Illinois at Chicago, which created a gentrification index for understanding how to measure neighborhood change in the city, for better or worse. The index measures 13 indicators of neighborhood conditions, including race, income, house values, education, and even the percentage of kids attending private schools. The findings confirmed and challenged some of our own notions, but the main takeaway is that gentrification is not as pervasive throughout Chicago as conventional wisdom might suggest.

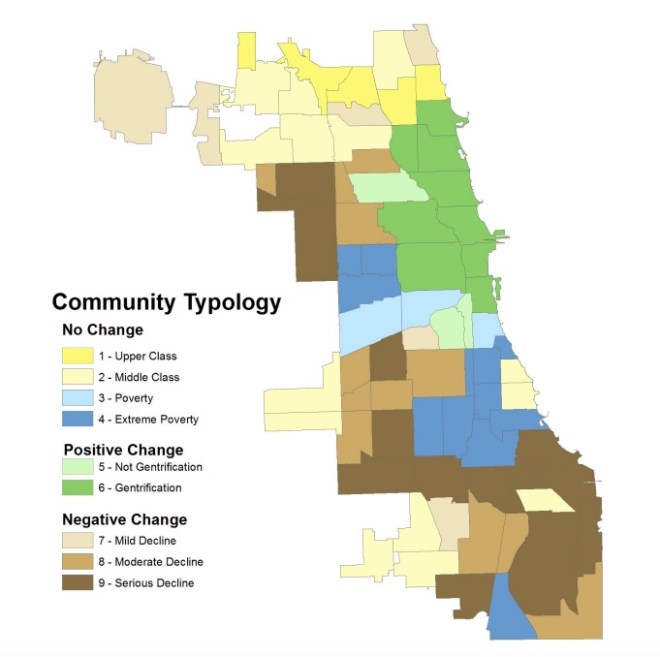

Scoring neighborhoods based on the index, Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods were grouped into nine categories ranging from “stable upper/middle class,” meaning index scores remained high since the 1970s, to “severe declines,” meaning those scores dropped significantly since the ’70s. The “gentrification” category captured neighborhoods that had low index scores in the 1970s, but grew significantly higher by 2010. There were only nine neighborhoods that fit that “gentrifying” classification, almost all of them in downtown Chicago (“The Loop”) or just north of it, areas that have been historically white. These places were basically immune to the housing crash, but meanwhile a glut of luxury high rises cast shadows over Lake Michigan.

The category you want to pay attention to, though is “severe decline” — 14 neighborhoods found mostly in South and West Chicago have populations that are, on average, two-thirds African American. Add those to the 12 neighborhoods that have remained in extreme poverty since the ’70s, of which 94.5 percent of residents are African American.

Black middle-class neighborhoods are falling behind, also, with median incomes and home values dropping in places like Washington Heights, Roseland, and Pullman. Chicago not only has a shrinking middle class, they also have a shrinking population. It hasn’t helped that there’s been a loss of affordable housing in some of the most desirable areas. The net result, according to the index, is that more neighborhoods show decline or no change at all than have gentrified — or rather, improved.

University of Illinois Chicago map of neighborhoods that have changed since the 1970s according to its gentrification index.

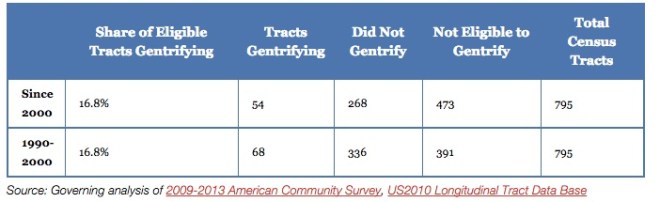

Policymakers, hence, must address the concerns of inequitable development across neighborhoods and income inequality, which are both also national issues. According to a City Observatory report examining urban poverty released last year, the problem over the past four decades is not wealthy whites infiltrating black and Latino neighborhoods with designer Pulaski hatchets and vegan cupcake shops. Governing magazine came to similar conclusions, showing low percentages of gentrified Census tracts in Chicago since 1990.

Governing magazine’s analysis of gentrification in Chicago by Census tract.

Some black neighborhoods have experienced upgrades that constituted positive change: Bronzeville, Woodlawn, Washington Park, and Oakland all saw an influx of black middle-class homeowners as the city demolished public housing. New services like better parks and streetscaping came along, but it hasn’t been enough. The announcement that Whole Foods is coming to Englewood, a low-income, black neighborhood, spurred fears that these new services and amenities aren’t for the low-income African Americans already living there, but are signs of wealthier whites coming. Walter Robb, Whole Foods’ Co-CEO, has insisted in my talks with him that this is not the case.

Chicago is a city of neighborhoods where identity is strong in all quarters. The city as a whole is just about equally black, white and Latino. Conversely, racial polarization persists even amidst city-wide diversity. Developers continue to build high-rises downtown, while the housing market limps along in parts of the South and West Sides. Wealth and poverty thrive in Chicago, but often on opposite sides of town, and with racial implications.

As Janet Smith, one of the University of Illinois-Chicago researchers who helped create the gentrification report, told me, “What we find is retailers still have an aversion to black consumers.”

Property values and rent have gone up in Logan Square, a fast-changing neighborhood on Chicago’s Northwest Side where developers are grappling with what to do about working-class Latinos who are being displaced. Residents are paying attention and are miffed, amid rumblings of “two Chicagos.” This month begins Chicago’s mayoral race, and incumbent Rahm Emanuel is seeking reelection. A recent Chicago Tribune poll showed that 62 percent of undecided voters believe the mayor hasn’t devoted enough attention to neighborhood economic development.

So, what kind of policies can help fix neighborhoods sagging from economic crisis, build a tax base, and lessen the gaps between the haves and have-nots in Chicago? A focus on density should probably be left in the 20th century. Family structures have changed. Large immigrant families don’t comprise most neighborhoods in Chicago anymore. Some communities want to remain bedroom communities, and probably should.

But good ideas run the gamut: Some residents are organizing around using tax-increment financing tools to draw new retail to blighted buildings — though not to be used as a shadow budget for upscale development. The Cook County Land Bank promotes redevelopment of vacant, abandoned, foreclosed, or tax-delinquent properties by cutting red tape. Residents in one North Side neighborhood want to curb the onslaught of higher rents by establishing a community land trust, which would acquire properties in the neighborhood, and then rent them out.

The ideas aren’t exactly sexy. People want to see big, visible economic drivers — like the South Siders who are waiting with bated breath for the possibility of an Obama Presidential Library coming to their neighborhood. But few developers are rushing to bring large, expensive developments to black neighborhoods.

As Smith told me, “Even if they have the green, they’re still black.”

Natalie Y. Moore is a reporter for WBEZ-Chicago. She’s working on a book about segregation in her city.