City retailers tend to overestimate the importance of parking to their business. They fail to see the many downsides of free parking (congestion and low shopper turnover, among them). They believe more people arrive at the store by car than actually do. They may not even realize that while driving customers spend more per visit, non-drivers spend as much or more in the long term.

And yet whenever a city considers installing a bike lane, rest assured some retailers will protest the perceived loss of automobile access. Take the bike lane that stole a dozen parking spaces from 65th Street in Seattle a couple years back (for reasons that will seem far less arbitrary in a moment). The typical comment from a bike lane opponent to the city’s department of transportation went something like this:

Please do not take away the 65th St. traffic lanes for bicycle lanes. Traffic is congested already and eliminating street parking for cars will [be] detrimental for all small businesses located on 65th.

If you find such claims strong on emotion and light on empiricism, you’re not alone. Kyle Rowe, who’s studying the built environment at the University of Washington, decided to put that standard retail response to the test. He put together a case study to see whether businesses really had a beef with bike lanes, or were making a fuss about nothing [PDF; via Transportation Issues Daily].

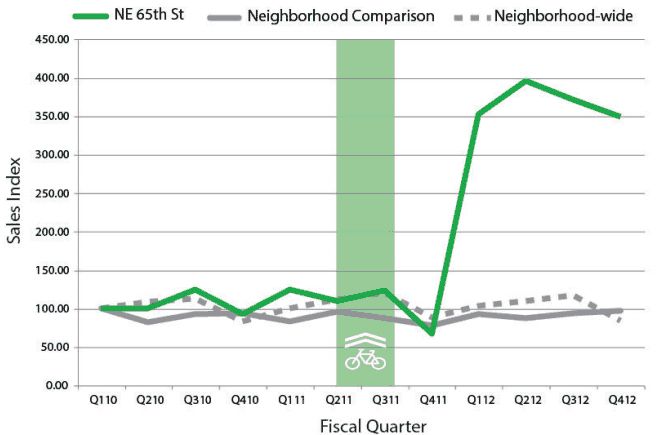

Rowe collected city data on taxable retail sales in the corridor before and after the bike lane on 65th Street went into place. He compared the 65th Street sales figures to those generated by a similar retail corridor where no changes had been made to the street, and also to the sales made by retailers in the entire neighborhood. What he found isn’t exactly subtle (the green bar is when the lane was installed):

So that happened. After the city removed 65th Street’s 12 parking spots and striped a bike lane there instead, the sales index in the corridor exploded 400 percent. Now keep in mind that Rowe didn’t have the experimental controls to say that the bike lane caused the increase — some other factor may have played a greater or contributing role — but it’s quite safe to say business didn’t suffer from it.

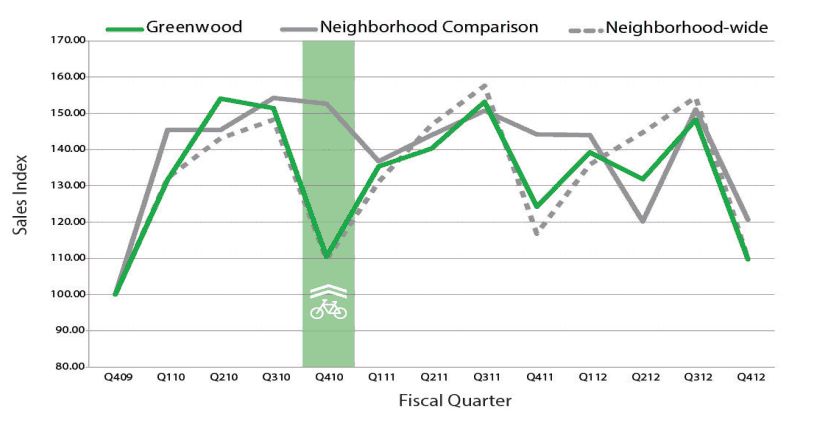

To make sure 65th Street wasn’t a fluke, Rowe also looked at a lane installed in the Greenwood district. There the city removed an entire lane of traffic as well as a few parking spots to accommodate the bike lanes. Once again Rowe compared taxable sales in the corridor to a similar strip and the neighborhood at large. Here’s what he found:

Those results don’t look too special — especially after the 65th Street chart — but that’s kind of the point. Business didn’t spike in the Greenwood district once bike lanes were added, but it didn’t plummet, either. It did about as good as everywhere else in the area. Writing at the Seattle Transit Blog last month, Rowe says the unequivocal takeaway is that bike lanes have no “negative impact” on retailers:

Looking at the data, one conclusion can clearly be made, these bicycle projects did not have a negative impact on the business districts in both case studies. This conclusion can be made because in both case studies the business district at the project site performed similarly or better than the controls.

Rowe’s isn’t the only recent study of its kind. A very fresh analysis of how bike lanes (and pedestrian improvements) impact retailers in New York reached similar conclusions. At best, retailers in a corridor seem to benefit from the change. At worst, they can still count on business as usual.

This story was produced by Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.