Alex Washburn was one of those New Yorkers who stayed put, defying Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s orders to evacuate when Superstorm Sandy came stomping into town. But unlike those who dug in their heels out of stubbornness or helplessness, Washburn stuck around out of pure curiosity. He’s Bloomberg’s chief urban designer — the guy responsible for shaping the city’s parks, streets, and other public spaces — and he wanted to meet Sandy in person.

“I wanted to watch, feel, understand what a storm surge meant,” he says. “If I don’t understand it viscerally, I can’t design for it.”

So while his family and many of his neighbors headed for higher ground, Washburn sat in his 19th century Red Hook rowhouse and watched.

“The first inkling was water coming out of the storm drains,” he says. “It rose very, very fast. Within minutes it had turned into a river. A little later, I remember looking out, and the power had gone out. It’s brown dark, it’s not black dark, and here I am in New York and there’s water between every building.”

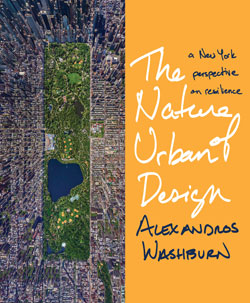

Washburn, who dropped by the Grist offices a few weeks back while promoting his new book, The Nature of Urban Design: A New York Perspective on Resilience, compared the sight out his window that night to the view of Mount Rainier on the Seattle skyline. “I got that sense: I don’t care what we do. That is big. That water was going to go where it wanted.”

And that included Washburn’s house. The storm surge, which peaked at about 12.5 feet, swamped his basement, rising about three feet inside his ground floor.

Months later, with the mess largely cleaned up, Washburn’s biggest challenge began: Figuring out how to defend against the floods next time. In the process, he has discovered that the kind of innovation and outside-the-box engineering required to make coastal communities resilient to storms like Sandy often runs counter to rules and regulations that were designed for tamer times.

Washburn’s story has implications that reach far beyond his historic neighborhood: His house, like thousands of others along the Eastern Seaboard, is now officially inside a federally designated flood zone. Many homeowners are suddenly faced with skyrocketing insurance premiums — and if they can’t find a way to make their homes water-tight, those bills will soar even higher, if they can get insurance at all. Becoming resilient, in other words, has just become imperative.

Washburn’s first idea for hurricane-proofing his house was something out of a steam punk fantasy. He would build a false floor on his ground level that could be ratcheted into the air with a series of pulleys and cables tied to the joists above. “All the furniture stays there, maybe you lay the standing lamps on their side, but if a hurricane is coming, you just crank it up,” he says.

Washburn’s first idea for hurricane-proofing his house was something out of a steam punk fantasy. He would build a false floor on his ground level that could be ratcheted into the air with a series of pulleys and cables tied to the joists above. “All the furniture stays there, maybe you lay the standing lamps on their side, but if a hurricane is coming, you just crank it up,” he says.

Points for creativity, but neither the local building code nor the federal insurance requirements would accommodate such a scheme.

Washburn’s next idea: Dry-floodproof the ground floor of the house up to the level that the federal government deemed a likely limit for future deluges — the “flood resilient construction elevation,” or FRCE, in FEMA speak. If a flood came, his basement would still fill with water, but the ground floor would stay dry.

Problem: According to the federal flood insurance rules, your “lowest occupiable floor” must be floodproof — and that meant the basement. “The Buildings Department told me, ‘Fill it or dry it,'” Washburn says. “Those were my only two options.”

He didn’t want to fill it. He’s considered turning the ground floor into a cafe or restaurant, and the basement would be critical storage space. But if he dried the basement — that is, made it waterproof — it would suddenly become a lot like a boat: When the floodwaters poured in all around, the house would want to float. “It’s gonna lift your house right off the foundation,” he says. “It would just destroy it.”

“No problem,” replied the engineers. “We’ll just tether your house to the bedrock. We do it all the time with skyscrapers in Manhattan.” It would set Washburn back about a million bucks, of course. Back to the drawing board.

Washburn cooked up more ideas, and each time, they were swatted down by one rule or another — or beaten back by the laws of physics. His plan to pour a thick concrete slab in the basement to serve as a ballast backfired because it would make the house so heavy it would sink into the soil. A proposal to inject the earth with grout to help buoy up the house created as many problems as it solved.

Washburn even cooked up a scheme by which he would pump groundwater away from the house and into the receding floodwaters following a storm surge. He called it a “hydrostatic equalizer;” the engineers dubbed it “the Washburnizer.” No word on whether the thing could really work — or how he would account for the neighboring rowhouses, which are attached to his.

More than a year after riding out Sandy, Washburn has identified only one straightforward fix — he calls it “the regulatory path of least resistance”: Fill the basement with dirt and turn the ground floor into a parking garage where floodwater can run freely in and out. (Picture the beach houses built on barrier islands up and down the East Coast.) But like any good urbanist, he dismisses that idea out of hand.

“Our neighborhood would die if everyone built a see-through parking garage under their house at street level,” he says. “Our bakery would go, our wine store would go, our neighborhood bar would go — all turned into parking. That may be a regulatory option, but it is not a community option.”

Perhaps what Red Hook needs is a Dutch-style sea wall that protects all of the houses from the rising tides. But that would require action — and funding — from Congress. Washburn, who spent years working for the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.), says that’s not happening any time soon. “There is just not that ability that we would expect of the United States of America, to say, ‘This is a big problem that demands a big answer,’” he says. “The rational process [in Congress] is off the rails.”

Nor does he take kindly to suggestions that his neighborhood may have to give way to the rising seas. “This idea that, ‘Well, why don’t you just get out of Red Hook, move to Cleveland’ — that kind of retreat talk, I do not believe in it. It goes contrary to the spirit of the city, which is to stand and fight.”

Of course, when you fight Mother Nature, you’re apt to take a beating, as Washburn learned last year, watching the floodwaters boil in the city streets. Still, he’s convinced that there are ways to work with nature, tai chi moves that will allow us to channel its energy away from the places we care about most. Many of those moves start right on the street level, he says — one house, one block, one neighborhood at a time.

Washburn is testing that theory right now, of course. But that, in a nutshell, is what his book is all about. It’s perfect reading for a rainy, rainy day.