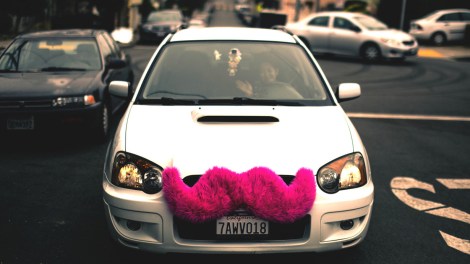

Alfredo MendezThe pink mustache marks this as a Lyft car.

The urbanist fixation with new car services such as Uber and Lyft can seem paradoxical. Why is it good for the environment and for cities to increase the number of cars for hire on our roads? The same could be asked about regular old taxis, and car-sharing services like Zipcar. Aren’t cars bad for the environment?

For the rare person who already lives car-free in a city such as San Francisco, a cab ride or car rental might actually increase their carbon footprint. But the vast majority of American households do own cars. For any city as a whole, more car-sharing and cab apps will actually mean less driving and lower carbon emissions.

To understand why, you have to consider the role that these alternatives play in a region’s transportation network. Eric Jaffe of Atlantic Cities did a great post on this in 2012, drawing on the work of Columbia University professor David King. King mapped New York City taxi rides on a typical weekday and put together a time-lapse video showing where they began and ended. Here is what he found, via Jaffe:

King sees an important pattern for the data points: the origins and destinations have a geographical asymmetry that suggests people are only using cabs for one leg of their daily round trip. If this were a video of people driving their own car to and from work, the morning and evening rush would be a perfect mirror. It stands to reason, then, that the other leg of the trip is taken by public transportation.

This means that cabs are not an alternative to New York’s public transit infrastructure but rather a part of it. They make it easier for you to leave your car at home for the day, or possibly get rid of your car altogether. King explained in a blog post about his study that cabs are an important component of good urbanism. “If we want to have transit oriented cities we have to plan for high quality, door-to-door services that allow spontaneous one-way travel,” King writes. And, as Jaffe observes, studies of demand for cabs support the same conclusion.

In research from a few years back [PDF], Bruce Schaller, a former director of policy and the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, ran statistical models of cab activity in 118 U.S. cities and found three primary factors for taxi demand. Among them were the number of workers commuting by subway and the number of households that don’t own cars. Both factors support the idea of taxis as part of a wider public transport network.

If the carless are the people who need cabs, then it naturally follows that cab availability is essential if we want to promote car-free households.

New York City, which has by far the largest carless population in the country, also has the most options for carless people to catch a ride. In the fancy parts of Manhattan, it’s usually easy to hail a yellow cab on the street. In the outer boroughs such as Brooklyn, where I grew up, you can’t assume there will always be a cab outside, but you can rely on car services, which are like Uber except you call them instead of using an app. There are also small local car-rental companies, like the one four blocks from my parents’ house, something you would not find in a residential neighborhood of a typical American city. That’s because New Yorkers who don’t own cars rent them to go out of town, whereas in most places everyone is assumed to own a car and most rental companies are located at airports, aimed at visitors who fly in.

Upon moving to Washington, D.C., I was baffled, and irritated, to discover there were no reliable car services. You could not schedule a pickup in advance, and when you called for a ride you might have to wait an hour for the car to arrive, whereas in New York five minutes is typical. Now, Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar are helping to solve exactly this problem in D.C., allowing residents to quickly and easily order a car from their smartphones.

Still, even the limited taxi system D.C. had a few years ago was enough to prevent me from buying a car. I lived in D.C.’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood and worked at Politico in Arlington, Va., four miles away. Usually I got there via a 50-minute journey on the subway. I could have driven the distance in 15 minutes, and I thought about buying a car to shorten my commute, but it was actually cheaper to just take a cab on occasion if I was running late. If I hadn’t been able to hail cabs, I would have been more tempted to buy a car. And once I had a car, it would have made sense to amortize the cost of buying it by using it more frequently.

Car-sharing options like Zipcar and Car2Go reduce driving in the same way as cabs and services like Uber: by enabling people to get around easily even if they don’t own a car. As Bloomberg News recently reported, “For every vehicle that is used in a car-sharing fleet, automakers will lose 32 vehicle sales, according to a study this month by AlixPartners.”

And if you don’t own your own car, you won’t take so many car trips. When you have to drop $30 on a cab or a Zipcar rental, you will stop to ask yourself whether this trip is really worth it — and often you’ll say no.

Providing these alternatives is essential to expanding car-free living in areas that are a little less dense and centrally located than, say, Manhattan. The medium-density rowhouse neighborhoods where I grew up in Brooklyn and lived in D.C. are a good example. My parents occasionally need to use a car, but with the advent of Zipcar they no longer need to own one.

This is why it is so important that New York Mayor Bill de Blasio buck his donors in the yellow cab lobby and support the expansion of the city’s taxi program to make it easier to hail a cab in Harlem, Washington Heights, and the boroughs beyond Manhattan.

And this is why a city like Seattle — with lower density than Northeastern cities, but higher than most Sun Belt cities — should not be drastically limiting the number of cars operating under Lyft, Sidecar, and UberX, Uber’s lower-cost option. Seattle is the kind of city that will need more car-sharing and cab options if it hopes to get more of its citizens to go car-free. And if you’ve ever sat in Seattle’s rush-hour traffic, you know fewer cars on its roads would be a good thing, and not just for the environment.

We have only just begun to experience how location-based technology may free us from the yoke of owning, repairing, gassing up, and parking a car. As New York magazine pointed out last week, many cab riders are traveling the same route at the same time, and they could save money and reduce pollution through cab-sharing systems. But having easily available and accessible cabs is a necessary precondition.

Cabs are also part of what make city living an attractive option. They’re great for going home drunk.

And moving more people to denser cities has to be part of any long-term American plan to reduce our CO2 emissions and protect our wilderness areas. It may seem counterintuitive that making cars more accessible would actually reduce our dependence on them. But it’s true, and it’s awesome.