(1) It’s a beautiful morning at the Amtrak station in Emeryville, Calif. I am standing here waiting for the People’s Climate Train, which will take me and 170 climate activists on a four-day-and-three-night-long journey to the People’s Climate March, which happens on Sunday, Sept. 21, in New York City. It is 8:30 a.m. and I can barely manage to sip my coffee and stay standing at the same time, but there’s a small send-off rally taking place, and already, there’s a woman here in a full Statue of Liberty outfit. That’s how hardcore this group is.

“My 6-year-old granddaughter made me this sign for the march,” says Ayya Santussika Bhikkhuni, a Buddhist nun, to the crowd. The sign says, in rainbow marker, “Stop doing bad stuff! No fracking and tar sands!”

“I asked her how she knew what fracking was,” Santussika continues. “She said, ‘Duh. You told me about it when I was 5.’”

“Mother Earth has reached up out of the ground and touched every one of us!” says Pennie Opal Plant, of Idle No More, in stentorian, bell-like tones. “We are her immune response!” More cheering.

(2) Wait. Didn’t I just spend four days riding Amtrak as I moved myself and my stuff from the East Coast to the West Coast? I sure did. But when I got a last-minute chance to join the climate train, it seemed too interesting to pass up. Covering the environmental movement is my gig, and the experience would provide the perfect control study: I could compare traveling 3,000 miles in a train with no climate change activists to traveling 3,000 miles in a train with 170 of them.

(3) I have never in my life seen a group of passengers carrying so much food. This looks less like a four-day train jaunt and more like the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. A woman just walked by me carrying an entire flat of peaches. I suspect this has something to do with the Amtrak dining menu. While the railroad has promised to stock more vegetarian options for the dining car during the climate train segments, many passengers have guessed — correctly — that this is code for “$10 microwaved bean burger.”

(4) Another speaker at the microphone in Emeryville is Santiago from Venezuela, a kind-faced man in a polar fleece zip-up. He addresses the crowd in Spanish, while the woman next to him translates, first with great vigor, then with increasing uncertainty.

“He wants to. He wants to …” says the translator.

“He wants to salute the indigenous towns where he comes from,” shouts a young Latino guy from the crowd.

“He say’s he’s Bolivian …” continues the translator.

“Bolivarian,” shouts someone else.

“Go back to the jungle!” someone yells from the back of the crowd. I turn my head. Did that happen? It happened. And it came from that guy with long, flowing gray hippie hair and rainbow stovepipe trousers.

The rally proceeds as if no one heard anything. Later, when I ask someone on the train what’s up with rainbow pants, they say, “Well, he’s a Sufi,” giving a “what can you do?” kind of shrug.

(5) What’s different about taking a train with 170 climate activists? I have never smelled burning sage on Amtrak before. The later it gets in the evening, the more the bathrooms smell like the inside of a bong. When people try to pass you in the aisle, they don’t just touch you on the shoulder; they knead your arm like it’s a ball of dough. On the plus side, everyone is really generous about sharing their trail mix.

(6) Just before our train reaches Chicago, I am organizing my carry-on bag and realize that someone has rifled through it and stolen my iPad. My mind goes off in a Miss Marple tailspin. Who did it? Was it someone just passing through our train car? Was it the stylish social justice activists who were bragging to each other last night about their shoplifting skills? Was it the middle-aged woman seated next to me for part of the trip, who was bound for Lapeer, Mich., to visit her sister? Will the thief strike again?

“I feel you,” says one of the musicians at the front of my train car. “That’s how I lost my banjo. First you leave your banjo with your friends, and then your friends take it out and start playing it, and then they forget about it, and the next thing you know you have no banjo.”

“What can I do to support you in this?” says one of the train’s self-appointed facilitators.

“Just ask the conductor to make an announcement over the PA,” I say. “I’m seeing a lot of people leaving computers out. Tell them to keep an eye on their stuff.”

No one ever makes an announcement. “You realize,” I say, when I remind the facilitator for the third time that she hasn’t said anything, “that by not doing anything, you’re putting everyone else on this train at risk of getting their stuff jacked.”

She makes a sympathetic face. “What can I do,” she says, “to support you in this?”

(7) The conversations about the mechanics of organizing and protest are fascinating. These days, people seem a lot more scared of earthquakes caused by fracking than they are of tainted water, says Dr. Lora Chamberlain of Southern Illinois Fracking Moratorium. “I just show them my earthquake map,” she says, cheerfully. “This is brittle rock! The waves travel farther and faster!”

“When we were walking through refinery towns,” says Pennie Opal Plant, “we were worried people would throw things at us. What we found was exactly the opposite. We are at a time where we can no longer assume that people are going to be against us.”

Make sure you have a lot of grandmothers at your protest, says Marina Skinner, who worked as a deputy field organizer for President Obama’s first campaign. “When you see an 80-year-old person, that is your walking billboard.” And don’t be afraid to censor the protests that you are in charge of. “You are giving birth to a new movement,” Skinner says, “and one of the things that you learn in birthing class is that you are in control of your own birth. When Obama and Biden were campaigning, if someone was holding a sign that wasn’t their message, they just told them to take that sign down. It was as simple as that. The civil rights movement did it. You can do it too.”

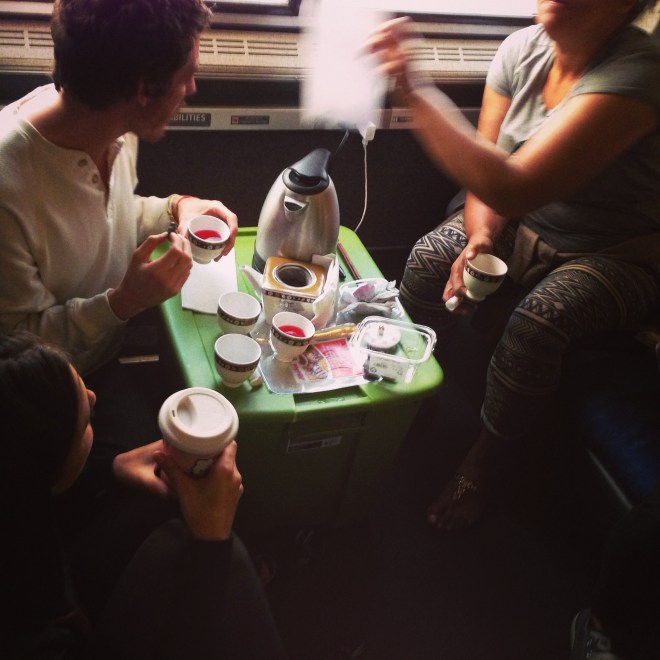

(8) The most self-sufficient contingent is from Richmond, Calif. Richmond is noteworthy for being both a refinery town and for having an extremely progressive, environmentally conscious local government. The Richmond contingent brought a rice cooker, which they use to make everything, including nachos. They serve hibiscus tea in tiny cups out of a teapot sitting on a plastic storage tub.

The older ones argue with the younger ones about whether or not it is a good idea to appear at Flood Wall Street — the direct action planned for after the People’s Climate March.

“I’m just going to go and look,” says Kal, an adorable fresh-faced representative from the Berkeley Ecology Center.

“We are going to have to have a talk,” says Stephanie Hervey, who works with a nonprofit called the Artisan Hub. “About whether a direct action is a safe place for young people of color in New York City.”

(9) It becomes apparent, after a while, that many of the people on this train are growing to hate us. The People’s Climate Train people make up about 80 percent of the passengers, so with their aisle-blocking, folksong-playing, Miseducation of Lauryn Hill-blasting, workshop-holding, and earth-centric arts-and-crafts making, there’s not much room for the usual pastimes of non-activist long-distance train travel — like sitting quietly and reading a book.

Among the People’s Climate Train riders, opinions on this are mixed. Some worry that we are giving a bad impression of the movement. Others think that the Amtrak conductors are acting like total sticks-in-the mud.

“I appreciate that you are all dedicated to your cause,” one of the conductors keeps announcing over the loudspeaker. “But stay out of the aisles.” When the train stops in Albany so that it can be split into two trains, one going to Boston, and one going to New York, the conductor comes over the PA for one final message. “For those of you going on to Penn Station,” she says. “I hope that you have good luck and I hope that you make a better impression.” The train breaks out into sarcastic whoops and applause.

(10) “I’m trying to practice non-attachment,” the very nice, silver-haired, tunic-wearing woman tells me. “But I just got kicked out of my seat because they’re having a workshop on Menstruation and Climate Change in my seat.”

Up at the front of the car, I can faintly hear the workshop in progress. Apparently, in the anaerobic environment of a landfill, your used tampons create methane.

“What else does wearing a tampon do to you?” the workshop leader says. “Anyone want to share?” Silence.

(11) When we finally pull into Penn Station, the crowd seems dazed. The riders are dispersing all over New York and its associated boroughs — to the floor of a church basement, to an Airbnb in Queens.

Then the banjos come out. The musicians on the train burst into the song they’ve been practicing for the entire length of the trip — a climate-specific version of the Curtis Mayfield song “People Get Ready,” which was originally written in 1965 about the civil rights movement.

Somehow, the moment is sweet, and perfect. Commuters moving through Penn Station stop and listen.