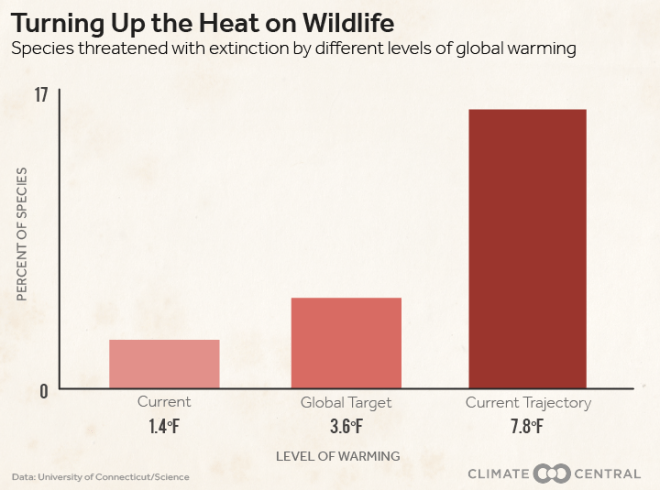

Cranking up the planetary heat is going to ratchet down the planet’s biodiversity, and new analysis suggests global warming could directly threaten 1-in-6 species with extinction if polluting practices continue unabated — up from about 3 percent today.

Scientists triggered alarm in 2004 when they warned in the journal Nature that climate change could drive 1 million varieties of plants and animals to extinction, but that was a rough estimate. In the decade since, researchers worldwide have been probing the dangers that could face individual species as climate change causes their ideal habitats to shift around them.

Those studies are collectively revealing a strong relationship between the amount of climate pollution that human activity pumps into the atmosphere, and the number of extinctions it’s ultimately projected to cause.

An exhaustive analysis of more than 100 such studies, which was published Thursday in Science, concluded that warming recorded since the late 19th century could drive a few out of every 100 species to extinction. The number of species threatened could rise substantially with every degree of additional warming.

“The extinction risks are really dependent on the amount of climate change,” said Mark Urban, a University of Connecticut associate professor who spent more than a year conducting the new analysis.

Vulnerable species are either expected to relocate too slowly as their ideal ranges morph and shrink or they’re expected to have no place to go.

The greatest risks to biodiversity were found to be in tropical regions and in South America, Australia, and New Zealand. Those places are all home to large numbers of species that have adapted to flourish within specific chunks of elaborate mosaics of tiny habitats, each harboring its own microclimate.

“The most species-rich places are the places where extinction risks are greatest,” said Lee Hannah, a climate change and biology researcher at the nonprofit Conservation International. He was one of the authors of the 2004 study, which he later expanded into a book, Saving a Million Species. “We have a lot at risk in the tropics.”

The extinction risks analyzed by Urban would be posed solely by climate change. The planet is already in the opening throes of what could become the sixth great extinction of biodiversity since life began nearly 4 billion years ago, with contemporary extinctions caused largely by habitat losses and unsustainable hunting and fishing. The extinction risks posed by climate change would compound many of those other dangers.

“The suitable habitat for some species disappears almost completely as climates change,” Urban said. “Think of a suitable habitat for a terrestrial species disappearing off a mountaintop.”

Hannah praised Urban’s analysis, saying it highlighted not only the need to slow global warming — but also to continue to rethink conservation strategies with climate change in mind.

Research shows that national parks, marine reserves and other protected areas can help protect species from a range of extinction threats, including those from climate change.

“If climate change is kept within some bounds, protected areas could be very effective,” Hannah said.

If climate change continues unabated, however, Hannah said “expensive solutions” might be needed to protect species, such as captive breeding programs and the physical relocations of plants and animals to more hospitable climes.