Ramon Navarro grew up on a rugged section of Chile’s central coast known as Punto de Lobos. It’s a craggy headland that extends from cacti- and pine-covered mountains into a long fingernail of cobalt-blue bay. It’s also one of the best cold-water big-wave surfing breaks in the world.

Navarro, 36, grew up in these South Pacific waters. As a kid he accompanied his father, a fisherman, on family fishing and diving trips. He eventually became one of Chile’s first professional surfers, and one of the best big-wave surfers in the world. In the process he’s become an activist and a local hero who has stood up to attempts to develop and industrialize his home. He once led a rally of thousands that were protesting the construction of a nearby pulp mill, fearing waste would end up in the ocean (the protesters won). Much of his inspiring story has been documented in the recent film The Fisherman’s Son.

We spoke to Navarro by phone, while he had a layover in Holland, about his arc from the family fishing biz to pro surfing to ocean advocacy. Here’s an edited and condensed version of what he had to say.

“Mostly people rode horses”

“I was very lucky to be born in Pichilemu 36 years ago. No one really knew about its surfing potential then, or even how to surf. It was pure. There were no houses, not many cars around, mostly people rode horses. Punta Lobos was considered a journey from Pichilemu, separated by a really bad dirt road. Now it takes five minutes. There are three waves in town, each very good. The winters are harsh, and the water is very cold, but it’s really consistent for surfing. Back then it was pretty magic — there were so many fish and not many people. It almost seems like a dream now.”

The fisherman’s son

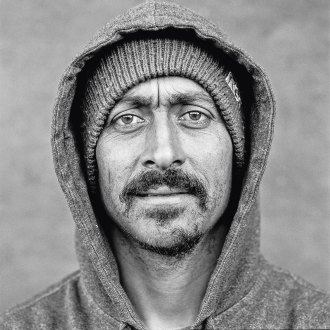

Ramón Alejandro Navarro RojasJeff Johnson

“A normal day for my father was to wake up really early, check the conditions, and check the nets. When I was about 7 years old, I started going with him and learning about the ocean. Learning to read it and how to respect it. There were lots of Chilean seabass. When the waves weren’t big, you could dive for rockfish like grouper. Also, lots of seaweed to harvest, and mussels, including a really expensive kind we called ‘locos’ that are similar to abalone. I still go with him today and do those things.”

Threats to the Chilean coast

“The main problems are industrial and commercial fishing. They’ve pretty much destroyed the fish in Chile. These days it’s almost impossible to get a seabass. It’s really bad for people like my dad and other ‘little boat’ fisherman. The other problem is construction. The development is happening so quickly, and there’s no access for the public. Beaches like Puertecillo have amazing waves and good fishing and diving, but people are trying to makes these places private.”

The pulp mill protest, 2003

“The mill had commissioned all these studies saying it was far enough away from the coast, but we understood exactly how the sandbars worked, how the current worked, and how the winds worked, especially in the summer. We were just a group of fisherman and surfers, but we knew they were wrong and that once they made that mistake there was no going back. So, basically, we went to a lot of the local meetings to tell people.

“It was never intended as a political action, we just wanted the community to know what the consequences were. I presented these ideas to the company and it became clear they had no idea what they were talking about. The next day we saw all these machines lined up there and so we just blocked them. It was basically just the whole town, then fishermen and surfers from around the country started showing up. We were about 10,000 people.

“We were trying to convince the mayor of Pichilemu, so one morning we did a big beach cleanup, with the whole crowd, and we decided to dump it all in his office. It was pretty crazy with police around, but it was the first time the whole community gathered to make something happen.”

Small victories add up

“Chile is trying to push its economy really hard right now. Every one is happy in the moment, but they’re not seeing what’s going to happen in the future. For example, a big project like HidroAysen, a mega dam and hydroelectric project in Patagonia. All the industries and markets were trying to make it happen, but after years of fighting it, it was finally defeated. That was one of the most amazing things I’ve seen happen in Chile.”

What’s next for Punta Lobos

“The goal is just to protect the point so no one can ever make a hotel or houses there again. We tried so many ideas in the beginning, and the main thing we decided is that if we buy the land no one can ever build there again. We’re gonna turn it into a protected reserve, with a lodge and bathrooms, so that everyone can have access, take care of it, clean up after the park. We tried to do something with the government for years, but the support wasn’t there. Now we’ve got businessmen from the local community, companies like Patagonia [one of Navarro’s sponsors], and the nonprofit Save the Waves, supporting the park.”

Surfing and conservation

“All the time, big wave surfing shows you things that you’re not going to see in normal surfing.

When you’re putting your life on the line, if you don’t understand something it’s gonna come back to bite you. You need to be humble, you need to show respect, and understand that the ocean is the main boss. If you’re trying to fight against the ocean you’re never going to win. You can get a few waves, but the big boss is going to have the last word.”