DVIDSHUBAn aircraft releases fire-retardant over Black Forest, Colo.

Last year, Colorado suffered from a record-breaking wildfire season: More than 4,000 fires resulted in six deaths, the destruction of 648 buildings, and a half a billion dollars in property damage. Still reeling, Coloradans are once again fleeing in their thousands from a string of drought-fueled fires.

So what role is climate change playing in the worsening wildfires? Here’s what we’ve learned:

Is climate change making wildfires worse?

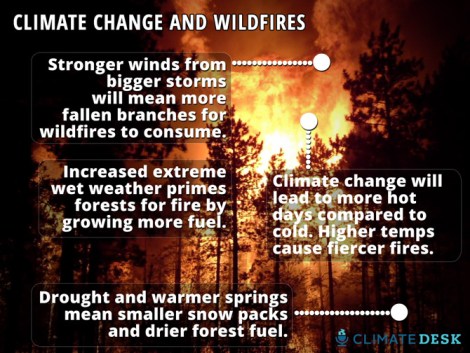

Big wildfires like Colorado’s thrive in dry air, low humidity, and high winds; climate change is going to make those conditions more frequent over the next century. We know because it’s already happening: A University of Arizona report from 2006 found that large forest fires have occurred more often in the Western United States since the mid-1980s as spring temperatures increased, snow melted earlier, and summers got hotter, leaving more and drier fuels for fires to devour.

Thomas Tidwell, the head of the United States Forest Service, told a Senate committee on energy and natural resources recently that the fire season now lasts two months longer and destroys twice as much land as it did four decades ago. Fires now, he said, burn the same amount of land faster.

How many more fires are we talking about?

We can expect “as much as a fourfold increase in parts of the Sierra Nevada and California,” in fire activity across the rest of this century, says Matthew Hurteau, assistant professor of ecosystem science and management at Pennsylvania State University. It’s a trend likely to continue: A 2012 study in Ecosphere, the peer-reviewed journal of the Ecological Society of America, found a high level of agreement that climate change will fundamentally alter fire patterns across vast swaths of the globe by 2100: While some areas around the equator will see fewer fires, there will be striking increases in high altitude boreal fires in the Northern Hemisphere. Fire will even reach a thawing Arctic, which will be more capable of growing plants to burn.

Break it down for me. What’s driving the change?

Fires are much more likely to occur during periods of extreme heat. The draft National Climate Assessment report, prepared by more than 240 authors, says, “There is strong evidence to indicate that human influence on the climate has already roughly doubled the probability of extreme heat events like the record-breaking summer of 2011 in Texas and Oklahoma.”

Droughts are another major driver. Right now, nearly half the West remains locked in the worst drought in 60 years. The vast majority of Colorado — more than 70 percent — is experiencing “severe” or “exceptional” drought right now, setting the background to the current fires. Low levels of winter snow and spring rains in the Western states don’t bode well for this year’s fire season, either. “The forest is much more flammable,” Hurteau says. Heat sucks the moisture out of forests, making them more susceptible to ignitions from lightning. And there’ll be many more hot days to contend with: Research has shown that ratio could increase to about 20-to-1 by mid-century and 50-to-1 by 2100.

This is further complicated by the role of climate change on the Gulf jet stream, which government scientists said earlier this year failed to deliver moist air from the Gulf of Mexico northward like it normally does, denying much of the continental U.S. of much-needed rains. Drought and subsequent wildfires may also be driven by weather systems thousands of miles away: A 2012 study also links a warming Arctic, and its affect on great global currents of air and water, with increased instances of extreme weather, including drought and heatwaves in the U.S.

There could be another nasty cycle at work here, too: U.S. forests currently absorb about 16 percent of all carbon dioxide emitted by fossil fuel burning in the U.S. By destroying trees, wildfires not only release carbon dioxide, they potentially alter their ability to absorb carbon, in turn meddling with amount of carbon in the atmosphere that leads to global warming … and more wildfires.

81firegal / Photobucket / James West

Rising temperatures I get. But isn’t climate change meant to produce wetter conditions?

That’s true. As the air gets warmer, it can hold more water. But “we’re alternating between periods of extreme wetness and extreme dryness,” says Lee Frelich, director of the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology. A warming world may produce a higher average precipitation and a higher average humidity, but fires perversely enjoy this, says Frelich: It means they can feast upon even more forest fuel once conditions snap back to dry and hot.

What about wind?

We do know with great certainty that when the wind is higher, fire behavior changes, whipping up embers through the forest canopy that can jump highways and even lakes. That’s certainly the case in the current Colorado fires, with the National Weather Service warning of gusts of up to 35 mph.

But is there a link between climate change and windy weather? A Canadian study from 2009 found that projected increased fire correlated with a slight increase in wind speeds, but the exact climate connection isn’t known yet. We do know that intense storms will become more frequent due to climate change — and that increased likelihood of storms with high winds means more fallen branches. Fire ecologists call this debris “slash fuel.” Add some “ladder fuels” — understory plants that grow in the shade — and you have an easy pathway for fires to leap up into the forest canopy, where they gain momentum. Frelich says Minnesota is still seeing the effects of built-up fuel from a deadly 1999 derecho, a fierce wind storm that blows in a straight line across a landscape accompanying bands of thunderstorms and rain.

Couldn’t we prevent all these mega-fires by getting rid of the smaller ones earlier?

You might think that tackling fires before they roar out of control is the best way to prevent death and destruction. Last year, the U.S. Forest Service briefly flirted with an “aggressive initial attack” plan. But evidence suggests the early intervention approach may actually produce bigger fires: By burning out dry undergrowth, small fires can actually help prevent large and deadlier blazes. Fighting every little fire might also put more firefighters at risk and deplete strained budgets.

Are we making it worse by building more houses in fire-prone areas?

Development doesn’t necessarily make fires worse, but it does put humans right in the path of destruction. I-News, an investigative journalism group in the Rocky Mountains, last year discovered that, “In the past two decades, a quarter million people have moved into Colorado’s red zones — the parts of the state at risk for the most dangerous wildfires … 1.1 million Coloradans live in more than half a million homes in red zones across the state.” The Forest Service’s Tidwell also told the Senate yesterday that more than 40 percent of U.S. forests are in need of hazard reduction, but that’s a tall order in the era of sequestration.

I’ve also heard about beetle outbreaks making fires worse?

While the science is still being debated, the fear is that dry, beetle-ravaged trees combust more quickly than their non-infested counterparts. Over the last decade, higher temperatures caused by climate change have allowed the pine beetle and the spruce bark beetle to survive the winter, causing the biggest outbreak in the last 125 years, killing pine forests across extensive areas of Western U.S. and Canada. The beetles are also venturing to higher altitudes where trees are more susceptible to the infestations. Since 1996, spruce beetle has affected 1.2 million acres in Colorado and Wyoming. In Colorado, mountain pine beetle attacked more than 750,000 acres in 2011.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.