Much of the computing power that crunches the data for the Bloomberg financial empire lives in a building on Houston and Hudson, in Manhattan. It won’t be there for much longer, though. After Hurricane Sandy, having a data center three blocks from the Hudson River no longer feels like a great idea.

“I own my company,” former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg said at a press conference Tuesday morning. “I want to sleep at night. I do some things so I can do that.”

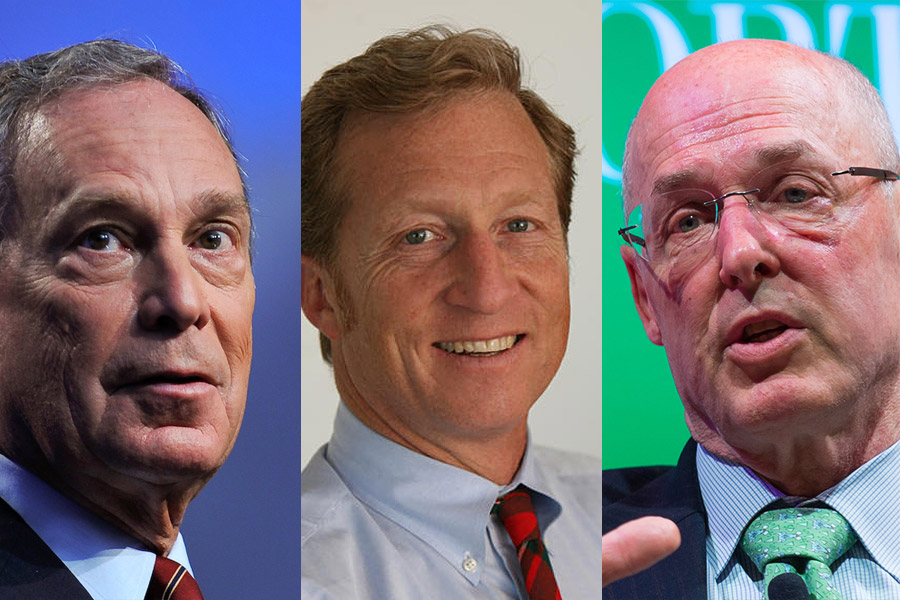

Bloomberg was there — along with Tom Steyer, Henry Paulson, and a bipartisan League of Superfriends-style “Risk Committee” of political and financial heavy hitters — to announce a project called Risky Business. The project, summarized in a report released today, is an ambitious attempt to spell out, in plainspoken, unvarnished business talk, the threat that climate change poses to the serious work of making money.

Many companies already run private climate-change risk scenarios. When I interviewed Kate Gordon, who has been managing the Risky Business project, she said that Shell Oil does war games and scenarios all the time based on climate change, but that those scenarios are locked up in company vaults. Now Risky Business has created a scenario that anyone can run.

It’s worth reading the report in full (or at least the bits that are about what calamities will befall your specific part of the U.S. under different emissions scenarios), in part because it’s so jovial and rah rah America — not a tone you regularly find in climate-change related discourse.

“Americans understand risk,” says the report, in its introduction:

Our ability to evaluate risk — to take calculated plunges into new ventures and economic directions and to innovate constantly to bring down those risks — has contributed immensely to the nation’s preeminence in the global economy. From the private sector’s pioneering venture-capital financing model to the government’s willingness to invest in early-stage inventions like the computer chip or the solar panel, our nation’s ability to identify and manage potential risks has moved the economy forward in exciting and profitable directions.

Exciting? Profitable? Tell me more, 56-page document! I read the whole thing, and here are the things that stuck out:

A hot America is an expensive America

Washington and Idaho will likely have more days above 95 degrees F each year than there are currently in Texas. Meanwhile, the Southwest, Southeast, and upper Midwest will likely see several months of 95 degrees F days each year, making those areas virtually uninhabitable without air conditioning. Air conditioning, though, will mean new power plant construction and higher utility bills.

Miami had better invest in stilts

Sea-level rise will be most damaging on the Southeast and Atlantic coasts — both because porous limestone along the coast makes it impossible to build flood barriers, and because people have built some fancy properties there. Within the next 15 years, higher sea levels combined with storm surge will likely increase the average annual cost of coastal storms along the Eastern seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico by $2 billion to $3.5 billion. If things continue the way they are now, by 2050 between $66 billion and $106 billion of existing coastal property will likely be below sea level across the country.

At the press conference, Risk Committee member (and former U.S. secretary of Health and Human Services) Donna Shalala mentioned that the architecture students at the University of Miami (where she is president) spend a lot of time thinking about how to retrofit buildings in the area for different levels of seawater rise. “The young people in our country get it,” Shalala said. “They’re our future business leaders.”

The U.S. climate is paying the price today for business decisions made a long time ago …

… as are a lot of businesses. Roads, infrastructure, utilities, and supply chains are already having to be rebuilt, and they’ll have to be again if they aren’t planned better this time around. Or, as Bloomberg put it, failing to anticipate a predictable disaster is the sort of thing that can force a CEO to step down: “If you have a plant and it gets flooded out, you’d better have a good retirement plan.”

Cities are bearing the brunt of preparing for climate change

Bloomberg argued that cities were at the forefront of planning for climate change — possibly because they have the most to lose. By definition, they’re stuck in a particular geographic region. The report calls this attempt to adapt without support from the federal government an “unfunded mandate by omission.”

The grain belt is in trouble

Some areas in the U.S. may benefit from climate change by having a longer growing season, but if they continue to grow cotton, wheat, and soy, several areas in the Midwest and South will likely see a 10 percent decline in yields over the next five to 25 years. California is already adapting to its drought by experimenting with olive production; other states should follow its lead.

Much of the science behind this comes from public sources — the Risky Business report has more on the process of coming up with these numbers here. “Our goal with the Risky Business Project is not to confront the doubters,” the report reads. “Rather, it is to bring American business and government — doubters and believers alike — together to look squarely at the potential risks posed by climate change, and to consider whether it’s time to take out an insurance policy of our own.”

I like this vision of American enterprise. I’m not entirely sure that I believe in it. The agricultural sector, for example, has seen climate change coming down the line more clearly than any other industry, outside of the reinsurance business. One of its less savory tactics for managing that uncertainty has been to game the farm bill so that the risk of climate change is outsourced to the Federal crop insurance program.

But that’s getting into the weeds of policy. The Risky Business report is all vision, and it should be read as such. Meanwhile, the World Bank just announced that tackling climate change would actually be good for the world economy, so expect to hear a lot more of this kind of talk in the future.