It was 2009, and Colin Foord was snorkeling along a seawall adjacent to some of the most expensive real estate in the country — Fisher Island, a stone’s throw from Miami Beach — when he happened upon something so unusual he didn’t even realize at first what he was looking at.

It was a coral, that much was clear. Thousands of the creatures had taken root on the granite boulders lining Government Cut, a man-made trench that gives cruise and cargo ships access to Miami’s port. But it would take a while before the marine biologist realized that he’d discovered a hybrid between two of South Florida’s rarest species: staghorn and elkhorn coral, both so scarce that the federal government considers them “threatened” with extinction.

By the time Foord understood what he’d found, he feared it was too late. January of 2010 delivered a record-breaking cold snap to South Florida. Orange groves were encrusted with ice. Iguanas froze and fell from the trees. In the Flamingo Marina in Everglades National Park, thousands of dead snook, tarpon, and goliath grouper floated to the surface and rotted.

For scientists watching coral, the devastation was stunning. More than 1 in 10 corals perished, according to one study. “We were losing all of the shallow-water corals in Florida Keys,” Foord says. “I was really worried. I thought we were going to lose the hybrid, and we hadn’t even had a chance to study it.”

But the hybrid survived. Foord says it didn’t even show signs of stress. In the silty, green-tinted waters a stone’s throw from one of the country’s largest cities, he had apparently discovered a species of urban supercoral.

His next challenge would be getting anyone to care.

This, it seems, is the fate of a good deal of “urban nature” — the tough weeds that push up between the cracks in a sidewalk and the creatures that subsist in the unused corners of our cities: We tend to overlook them, or to write them off as insignificant and unsexy when compared to the Wild Things and Big Wilderness far from the city limits. Urban ecologist Marielle Anzelone calls it “nature chauvinism.”

Miami’s supercoral was an interesting case in point. While both of its parents enjoy protection under the Endangered Species Act, the law makes no allowances for a cross-breed. Local environmentalists didn’t exactly rush to embrace the coral, Foord says. The notion that wild creatures are adapting to our increasingly engineered world runs somewhat counter to the traditional conservation tenet that holds that nature must be preserved in its pristine, unblemished state.

Foord’s fellow marine biologists were far too busy studying the widespread decline of corals elsewhere in the world’s oceans to bother with this urban misfit. And local and state agencies were equally unenthused: What kind of bureaucratic shitstorm would they stir up the next time they needed to upgrade the seawall, potentially disturbing the newfound coral?

Even the local science museum was lukewarm on the supercoral and the many other coral species Foord had documented in the waters off of Miami. When he heard that the museum was in the process of building a new, quarter-billion-dollar facility, Foord pitched an exhibit built around a native coral reef. The museum staff dismissed the idea, opting instead for more exotic looking corals shipped in from abroad. “Nobody wants to touch these corals,” Foord says.

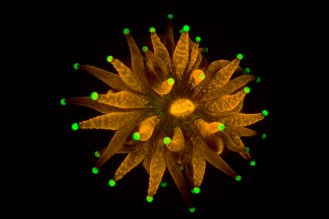

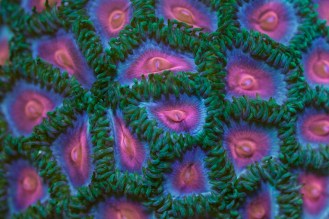

So when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced that it was going to scrape the bottom out of Government Cut to allow larger ships into the port, it was up to Foord and his childhood friend, musician Jared McKay, to save them. The two created a company called Coral Morphologic. They made their money selling coral in the lucrative home aquarium market, but their mission was to put a spotlight on what Foord calls Miami’s “original neon icons.”

During the Art Basel festival in 2010, the duo projected goliath images of corals onto the side of an office building in South Beach. They created a psychedelic film of Miami’s corals called “Natural History Redux” that could give Fantasia run for its money in the trip flicks department. Here’s a taste of it. (You can download the whole thing for a small fee here.)

Finally, Foord and McKay managed to get permits to collect and transplant corals from Government Cut before the Army Corps started work. The Miami Coral Rescue Mission, as they call it, netted hundreds of corals (several of which are pictured in this story). Most of them now live on an artificial reef about a mile from their original home. The rest sit in tanks in the company’s lab, where the duo continues to study and film them, most recently for a BBC documentary. The public can support their work by donating to the ‘Coral Morphologic Fund’ at the Miami Foundation.

It’s a lot of trouble to go t0 for creatures that grow in murky water, amid garbage and discarded shopping carts. But there’s much to be said for these hardy hangers-on. Naturalist and educator Molly Steinwald points out that urban, “mundane nature” offers urban dwellers a chance to connect to their natural world in a real and meaningful ways. Environmental planning professor Tim Beatley argues that in a warming, and increasingly urban world, integrating natural habitat into the concrete jungle will be crucial for both wildlife and humans. And students of “novel” ecosystems that are heavily shaped by humans point out that there is a tremendous amount of ecological diversity to be found in cities already.

Of course, a couple of peregrine falcons nesting on a skyscraper does not a healthy population make — you’re going to need large wilderness preserves for that. But Miami’s supercoral could offer a lesson in how tough, urban-adapted hybrids could be valuable to those larger populations as well.

Corals, which are anchored in place, have come up with some remarkable survival strategies. They can reproduce asexually, creating clones of themselves. But they also do it sexually, releasing clouds of sperm and eggs in to the water in massive, synchronized events.

Miami, it happens, is just a few miles from one of the most powerful ocean currents on the planet, the Gulf Stream. That current could easily carry gametes out into the ocean, seeding a new breed of corals that may well be better adapted to a warming world than their ancestors and cousins out in the Big Wild. (While South Florida and the Caribbean saw massive coral bleaching last summer, during especially hot and sunny weather, Miami’s urban corals seem to have fared well.) Clones of those corals could also be transplanted by hand to form the basis of new super adapted reefs in the wild.

“Worldwide, corals and coral reefs are in trouble and decline,” Foord says. “But in Miami, there are corals pioneering into the city, taking advantage of seawalls, discarded shopping carts, riprap along highway.

“Miami is a proving ground for these corals,” he says. “These are the resilient survivors.”