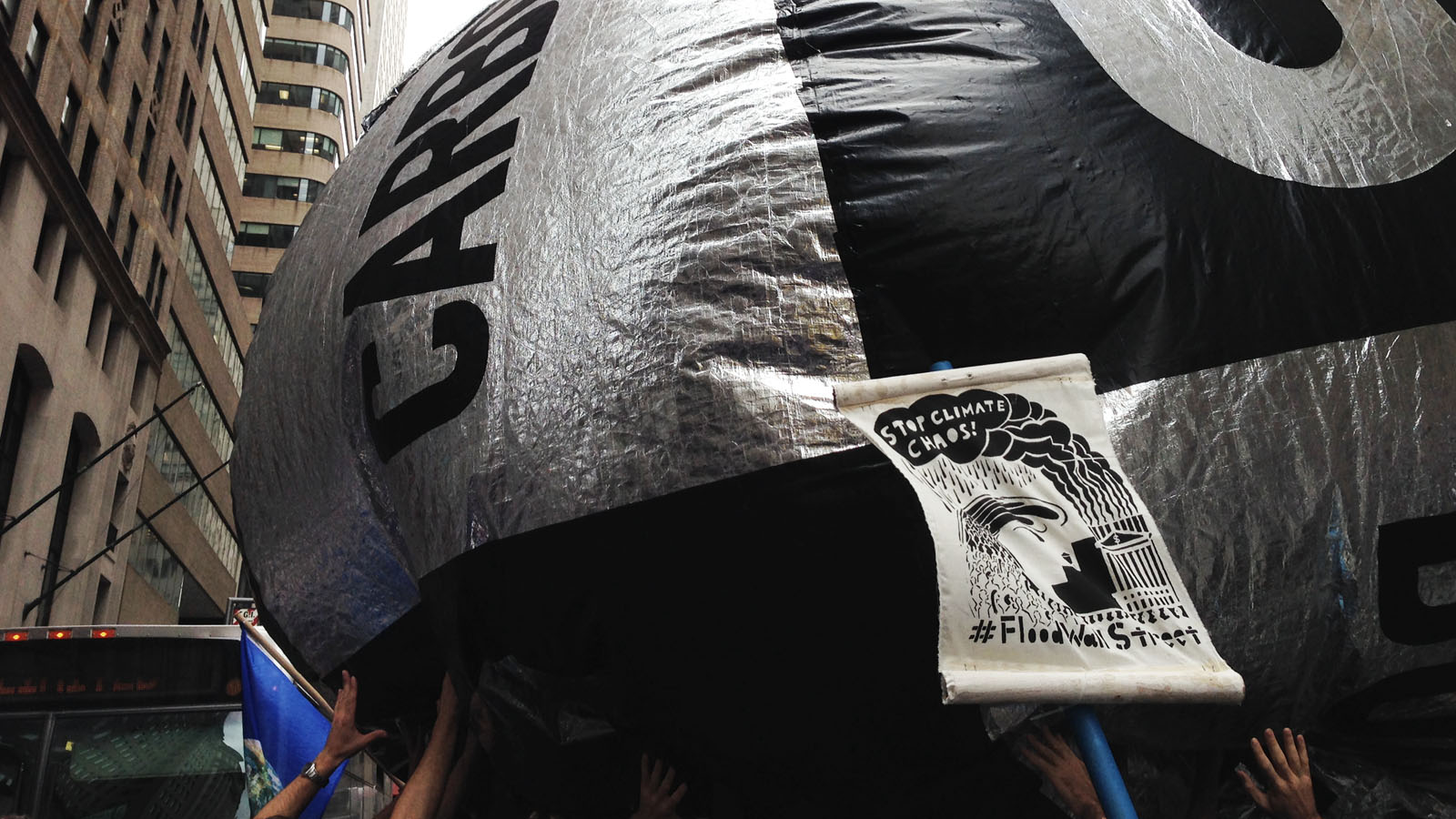

In my early days as a reporter, I learned to chase photographers the way that dogs chase cars, instinctively. That’s how, at last week’s Flood Wall Street protest, I wound up underneath the carbon bubbles. They were big, black, and silver and looked like enormous beach balls, and they were being held aloft by a horde of people surging down Broadway in the direction of the protest’s intended target: Wall Street.

I had seen them being inflated earlier, at the staging area in Battery Park, and hadn’t thought much of them. But now, seeing them surrounded by the skyscrapers of the financial district, they looked striking, both as art and as visual shorthand for a pretty abstract and wonkish economic concept — the risk represented to the world’s economy by allowing energy companies to base their value on coal and gas reserves that we can’t actually use without making climate change intolerably miserable.

DIY inflatables have been around since the ’70s, but I hadn’t ever seen them deployed at a protest before. They looked more like pop art than the social realism and folk stylings that I’d seen both elsewhere at Flood Wall Street and at the People’s Climate March the day before. “What is your story, bubbles?“ I wondered, as they were batted back and forth, squeezed in between tour buses, and eventually confiscated by the police and stomped on. “Where do you come from?”

Berlin, as it turns out — or at least that’s the source of their plans, which were drawn up by Artúr van Balen, of the Berlin-based arts group Tools for Action. The ones at Flood Wall Street were built by an all-volunteer crew at a warehouse in Brooklyn; a similar set was built in London for the Climate March there, and van Balen has posted instructions for anyone interested in making their own.

According to Katherine Ball, an artist who worked on the carbon bubbles along with van Balen, it was clear from the minute that they heard about the march that they had to make something for it. “I mean, c’mon,” she said, in a phone interview. “Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.”

That said, there were many other inflatables debated besides the bubbles. One idea was to make inflatable icebergs. Another was to make carbon bubbles, but out of latex and with microphones inside that would reverberate each time it was bounced. (“It makes a sound like nothing you’ve heard before,” says Ball.) That plan bit the dust when the builders discovered that latex glue in the U.S. just doesn’t hold a protest sphere together as reliably as a German glue can. It’s too much to hope that an inflatable object made by an all-volunteer crew is going to be completely airtight. (When Tools for Action builds an inflatable that actually needs to float, they fill the interior with individual helium balloons, instead of hoping that the skin of the inflatable will keep the helium inside.) But it needs to at least stick together.

So instead, the bubble was made out of black trash bags and the radiant barrier foil that is used to seal housing insulation. As it was, the crew that was carrying one of the carbon bubbles ran it into some trees in their excitement to leave the park – which necessitated on-the-street repairs with gaffer tape and a battery-powered boat pump.

In general, van Balen’s projects for Tools for Action have the qualities of large, squishy, socially progressive Claes Oldenbergs. Tools for Action built a 40-foot long silver hammer for the 2010 U.N. Climate Change conference in Cancún, Mexico; a 30-foot inflatable saw for an anti-corruption protest in Moscow; giant pink lungs that have been making the rounds to different coal-related conferences; an enormous rainbow that was lifted over the route of a swim marathon in Croatia in protest of the country’s discrimination against LGBT citizens (in local superstition, passing under a rainbow can change a person’s gender); and a 30-foot fake bomb made out of radiant barrier foil that was floated on the Hudson River outside of the West Point Military Academy.

All of this has granted Tools for Change entrance into a corner of the art world that is, for its own mysterious reasons, currently obsessed with activism and the DIY aesthetic. In one sense, Tools for Change makes giant protest balloons, for free, in collaboration with activist groups all around the world. In another sense, it is making artworks that have been shown at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Other artists who work under this umbrella include Swoon, who originally made a name for herself by wheatpasting enormous portraits of ordinary people in public spaces, and whose work is increasingly taking on environmental themes. I saw several of the portraits from her Brooklyn Museum installation Submerged Motherlands at the People’s Climate March, flanking the entrances to the Climate Ribbon project — which is designed to be, in the words of its organizers, “an AIDS quilt for the climate justice movement.”

Grist / Heather Smith

Inside the pavilion, people took turns stepping up to a microphone and reading a message that a stranger had left behind about what that stranger was most afraid of losing to climate change. The result was sweet and companionable and affecting, though a lot of that had to do with how nothing was really at stake – not for most of us, not yet. The whole exercise was thrown into a slightly different perspective when a contingent of marchers from Papua New Guinea, one of the places most threatened by climate change, stepped up to the mic, disregarding the read-a-stranger’s-message routine. “I will miss,” they said, one after the other, “Papua New Guinea.”

None of the art that I noticed at the People’s Climate March and Flood Wall Street made the big time in terms of media coverage and social-media reach. At Flood Wall Street, the carbon bubbles were barely noted at all. They popped early on, and it wasn’t clear that many of the onlookers (or protesters) even knew what they were. The image that was most circulated, and that came to represent the march, was that of a “polar bear” — a man in a polar bear suit — getting arrested.

Everyone at the protest had seen the polar bear taking his head on and off throughout the day in order to get some air. It did not look pleasant in there; the guy inside the suit looked like he was being gently steamed in his own juices. Still, after the bear was handcuffed, when the police lifted the costume’s head off, the crowd erupted with angry boos — as if the noblest thing to do was to keep this guy in his polar bear drag all the way to the county lockup.

When I described all this the next day to a friend, over lunch, she sighed at all the dress-up. “This is why they’re not getting anywhere. That’s not a protest. That’s Burning Man.”

I had spent most of the morning writing up my own story and poring over the coverage that other people had done, and it was strange to see the 12 hours that I, along with so many other reporters, had experienced get boiled down to a few images: the polar bear, the Captains Planet, the ubiquitous dude in dreadlocks scuffling with police. There had been plenty of people in regular street clothes at the protest, too, but there were certain aesthetic tropes that we all, as reporters and spectators, seemed to find irresistible. In the modern times we live in, perhaps all we really do want to see is a polar bear getting arrested.