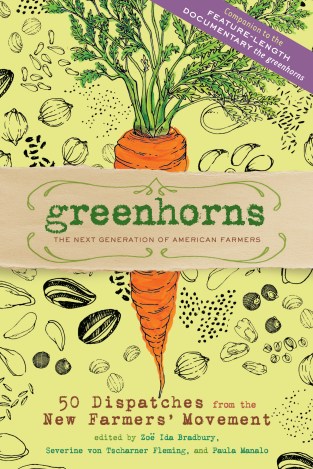

The following is excerpted from the new anthology, Greenhorns: 50 Dispatches from the New Farmers’ Movement, which was edited by Zoe Ida Bradbury, Paula Manalo, and Severine von Tscharner Fleming.

Photo by Geecha.

I didn’t notice the marks on the John Deere until I’d had the tractor for maybe a month. A couple of spots of brown, corroded metal etched into the green enamel on the top surface of the right fender. No big deal — a decades-old tractor should have all sorts of dents and dings if it’s been used for anything worthwhile — but the placement of these marks was interesting. Again and again, the times I noticed the marks was when I turned around to see the row behind me and placed my hand exactly upon them, the base of my palm on the larger spot, the tips of my fingers on the smaller. I can’t remember the moment now, but at some point while driving the length of one or another 300-foot row I finally got it: The marks were made by the hand of the previous owner. Every time he’d turned around to check his depth or adjust his steering or see the work he’d accomplished, he’d placed his palm on this same section of fender — an unconscious action that he must have repeated several hundred thousand times — and gradually his sweat had eaten through the paint and begun to corrode the metal.

Repetition is what we do here at the farm — animal chores morning and evening, picking the squash every day and a half, the beans and tomatoes every three days, the market and CSA pickups each week, spraying the foliar fertilizer every two weeks, the big clean out of the goat barn and the garlic harvest once a year, the three- and four-year rotations of the various families of crops — all these different time signatures in sync and then crashing against one another. There’s no way to do all that’s scheduled in a single day.

The tasks are completed in order, one after the other as time allows, but meanwhile there are all the ways that time on the farm overlaps and twines around itself.

We keep a log of all the things we intend to do differently next year (plant the first sweet corn a week earlier, don’t follow winter squash with carrots because of the weeds, don’t use biodegradable plastic under cantaloupe because the melons will rot). At the same time, wherever we are on the farm, we’re reminded of what was in the ground last year (volunteer cherry tomatoes, leftover potatoes, a weedy patch where the lamb’s quarters got out of control).

We keep a log of all the things we intend to do differently next year (plant the first sweet corn a week earlier, don’t follow winter squash with carrots because of the weeds, don’t use biodegradable plastic under cantaloupe because the melons will rot). At the same time, wherever we are on the farm, we’re reminded of what was in the ground last year (volunteer cherry tomatoes, leftover potatoes, a weedy patch where the lamb’s quarters got out of control).

There’s a very real sense, then, that we’re farming three years at once, tracking where we’ve been and calculating where we’re headed, even as we try to figure out — at this exact moment — what in the world to do with the 800 pounds of eggplant ripening in the field. (And this doesn’t take into account the perennials — the strawberries and asparagus and fruit trees — whose time signatures add an even greater level of complexity to the score).

We push and pull at time. Time pushes and pulls at us. We encourage the arugula to mature more quickly by laying down row cover, and then we load the freshly harvested broccoli into the cooler to make it last as long as it can. The bean pick we thought would take an hour ends up taking three but yields half the crop it did a few days before. The turkey that fit in the palm of my hand six weeks ago now can hardly be held in my arms. I try to squeeze a nickel out of a minute with each pint of cherry tomatoes I sell, but here’s what will ultimately last: the flavor of those tomatoes in my sons’ memories, so that even as grown men no other food will ever taste as good.

Time on the farm is not static, it’s not a given. It’s not like a ladder with all the rungs evenly spaced. Rather it’s a substance, a material we try to manipulate just as much as we do the tilth and the fertility of the soil. How many tomatoes can we harvest before the lightning storm arrives? How many can we sell before they rot? How can we get everybody out weeding the carrots this afternoon even though there are all those watermelons to pick? And how can I get November to come more quickly, so that Oona and Wiley and I can take a nap together and the killing frost will give me some hours alone to read?

It’s the end of August. We’re no longer shaping the rhythm of the season. We merely step into the morning and let the rhythm of the harvest shuffle us along. The products of this rhythm — the song, let’s say — are almost unbearably fleeting. The tomatoes get sold, the goat barn gets dirty again, the turkeys eat and eat and eat until they themselves are eaten. The products of an entire season’s labor are devoured by shareholders and crew and customers and neighbors and friends, and the residue is harrowed back into the ground.

This is why I like the marks on the John Deere. They’re a reminder, a register of all the countless repetitions we perform. The other farmer (a potato grower, I’ve heard, who recently passed away) and I sitting in the same seat, looking back as we travel forward, resting our palms on the fender to stabilize our bodies, putting sweat to metal, making food for people’s bellies — sure — but here’s what’s left: a small, corroded imprint of our hands.