I am not sure how the plastic honey bear got into my apartment. It’s unlikely that it is the kind of honey bear that is possessed by an evil spirit and moves into cupboards all on its own. Probably, a houseguest left it here.

What I do know is that, every time I open the cupboard door and find myself staring into its little black plastic eyes, I wonder: “Are you a fraud, little bear?”

I’ve known for years that, like a pile of Louis Vuitton handbags for sale on the sidewalk, a cheap jar of honey is probably a fake jar of honey. Maybe not all fake. But honey is expensive, and the supply chains are long and obtuse enough that people could add a little corn syrup here and there along the way with little chance of repercussions. And so they do.

This December, it took a food blogger to point out what was apparently an open secret in the fancy chocolate business: that the Mast Brothers, whose rugged beardy faces seemed to signify a more simple, trustworthy time, got their start as big chocolate fakers.

But there never was a more simple, trustworthy time. Fakery may feel like a modern phenomenon, a hazard of the globalization of food networks that has — so far — brought us marvels like the mafia-related horsemeat scandal in Europe and melamine in pet food and baby formula. (Melamine: It makes a perfectly good tabletop, but a very bad breakfast.)

Exhibit A: A treatise on adulteration of food, and culinary poisons, exhibiting the fraudulent sophistications of bread, beer, wine, spirituous liquors, tea, oil, pickles, and other articles employed in domestic economy. And methods of detecting them which I stumbled across when I was searching for old food books in the Philadelphia archive of the Chemical Heritage Society. Written by Friedrich Christian Accum and published in 1820 in London, the treatise was a surprise bestseller. (A thousand copies sold in the first month! At a time when only a little over half of Great Britain’s population was literate!)

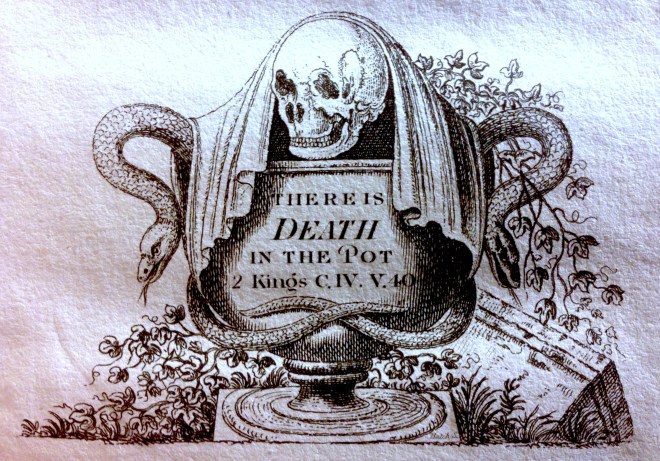

If you run across a copy — there are quite a few still out there, and the Internet Archive has thoughtfully posted scans of the book online — it’s not hard to see why the book went viral. For one thing, there are the illustrations:

1820s London was a few years away from becoming — some people say — the world’s most populous city, a title that it would hold until the 1920s. The city’s public transit system still lay in the future, and so did the Broad Street cholera epidemic that would go on to validate the emerging science of epidemiology. Accum’s treatise is a window into a world where urbanization and mass-production of food first began to widen the distance between producer and consumer. As the number of middlemen in the food trade increased, so did the number of bakeries that cut flour costs by mixing their dough with chalk or sawdust. Same with brewers who added strychnine to their beer; it was cheaper than hops, but with the same tart flavor.

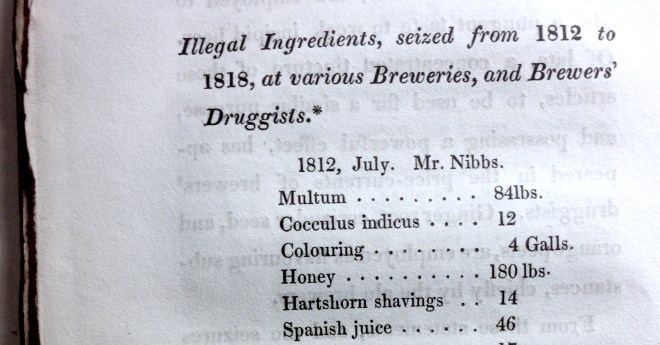

But London was still small enough that when Accum printed up a section in the book about who was in the food fraud business, it looked like this:

These were individuals. Locals. Albeit locals in a city that was already large enough to make strangers of the people who lived there.

Three years earlier, the British financial speculator David Ricardo published another book, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, which first set out the theory of comparative advantage as we know it today. If a country (say, Portugal) can produce a product like wine more cheaply and efficiently than another country (say, Spain), then, Ricardo declared, it’s good for both countries, and human society at large, if Portugal just makes all the wine and Spain drinks it. (Then, with a hangover, Spain has to find something else to produce to pay Portugal back.)

Ricardo’s theory went on to become famous — it’s often the first lecture in an Econ 101 class, and it’s constantly used to explain how certain companies and countries rise to market dominance. But it’s fitting that it was born around the same time as Accum’s treatise: One way to get a comparative advantage real fast is to do stuff like throwing chalk in your flour. And throwing chalk in flour gets easier the farther away you are from the flour’s eventual customer.

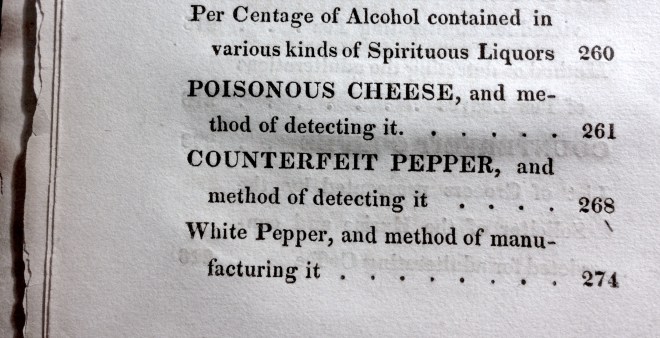

Accum’s book did more than name names. It also described how to detect when food had been tampered with:

The spurious pepper is made of oil cakes (the residue of lintseed, from which the oil has been pressed), common clay, and a portion of Cayenne pepper, formed in a mass, and granulated by being first pressed through a sieve, and then rolled in a cask. The mode of detecting the fraud is easy. It is only necessary to throw a sample of the suspected pepper into a bowl of water ; the artificial peppercorns fall to powder, whilst the true pepper remains whole.

And what was nearly impossible:

The adulteration of ground coffee, with pease [sic] and beans, is beyond the reach of chemical analysis; but it may, perhaps, not be amiss on this occasion to give to our readers a piece of advice given by a retired grocer to a friend, at no distant period: ” Never, my good fellow,” he said, “purchase from a grocer any thing which passes through his mill. You know not what you get. Instead of the article you expect to receive, coffee, pepper, and all-spice are all mixed with substances which detract from their own natural qualities.” Persons keeping mills of their own can at all times prevent these impositions.

Soon enough, Accum had competition. There was Bumpus and Griffin’s The Domestic Chemist: Comprising Instructions for the Detection of Adulteration in Numerous Articles Employed in Domestic Economy, Medicine, and the Arts, published in 1831. And there was the Food and Drug Administration’s Manual of Instructions for Officials, Analysts, and Inspectors Connected with the Food and Drug Inspection of the Bureau of Chemistry (1911), which was written a few years after Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, leader of the chemistry research division for the U.S. government, established a volunteer-staffed “poison squad” of young men who ate chemicals like borax, sulphuric acid, and formaldehyde, and noted the results.

Random testing of goods on supermarket shelves reveals a world where food fraud is still common. Maple syrup is often fake. Olive oil is often fake. The technology to catch fakery exists, but it’s expensive to use, and it can usually only show you something that a researcher suspects is there. Melamine evaded detection for so long because no one thought to test for it, and it may still be floating around in the food system.

Today, searching out food fraud is less about expensive testing than it is about old fashioned detective work — poring over shipping records, in particular. Startups like Sourcemap, based in New York, show the beginnings of what a more elaborate kind of supply chain mapping might look like. But right now such systems are far from perfect, and tracking the number of times a product changes hands is only one data point, anyway.

Such tools are likely to remain a step behind the fraudsters they are trying to expose. That makes the 21st century less different from the 19th than we’d like to think. In both eras, technology is only as good as the questions that the person using it thinks to ask.