Imagine you are a small farmer in a poor country, growing corn and a small mix of other crops to support your family. One year a drought destroys most of your harvest, and suddenly you — along with everyone else in the region — face the threat of going hungry.

You were able to salvage a fraction of the corn you hoped to harvest. The question is, what do you do with it?

You could keep it to feed your family. But processing corn takes an incredible amount of time and labor. And you can’t live on corn alone: You’ll need some money to buy other foods, and for the inevitable expenses (tool repairs, medicine for a child, etc.).

If you decide to sell some of your corn, where do you sell it? Prices are low in your region: Because of the drought, people can’t afford to pay what they normally do. But prices are higher to the north, where there was more rain and no threat of famine. The logical thing to do would be to keep some corn for your family and sell the rest for the best price you can get. But this logic means that, when there’s threat of famine, food tends to flow away from where it’s needed most, into more affluent areas. Hunger creates a demand for food, but wealth creates an even stronger demand.

When I started this hungry-hungry-humans project (you can find the previous stories here), people began preemptively warning me that I was probably headed in the wrong direction. They feared that I would start by asking: How are we gonna feed 10 billion people without wrecking the planet? And then answer it by saying, well technology X can increase farm yields by this much, and technology Y can bump it up a little more …

Instead of focusing on agricultural productivity, these people said, we should be working on access to food. We currently have plenty of food, and yet we still have hunger, even in the U.S. So how will increasing yields further help?

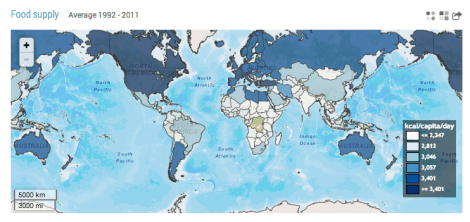

As Gordon Conway points out, in his book One Billion Hungry: Can We Feed the World?: “If we were to add up all of the world’s production of food and then divide it equally among the world’s population, each man, woman, and child would receive a daily average of over 2,800 calories — enough for a healthy lifestyle.”

And Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, has demonstrated that famines stem primarily from poverty, not a widespread food shortage.

“Famine has often taken place when statistics have shown little or no decline in food supply,” Sen wrote. “During the Bengal famine of 1943, for instance, the diminished purchasing power of rural laborers’ wages initiated widespread starvation. Similarly, in 1973, a famine in the Ethiopian province of Wollo was caused by a locally intense drought that impoverished the local population but did not substantially reduce food production in the nation overall.”

The key to preventing famines, according to Sen, is to create government programs that move resources and ensure that everyone gets food. And I like this next bit: If you want to prevent starvation, what you really need are journalists.

“It is significant, Sen wrote, “that no democratic country with a relatively free press has ever experienced a major famine (although some have managed prevention more efficiently than others). This generalization applies to poor democracies as well as to rich ones. A famine may wipe out millions of people, but it rarely reaches the rulers. If leaders must seek reelection and the press is free to report starvation and to criticize policies, then the rulers have an incentive to take preemptive action.”

Elke Wetzig/WikimediaAmartya Sen.

Does this mean that we can stop worrying about agricultural production entirely? Should we just ignore farmers, and instead focus on building democracies? Absolutely not, say the agricultural economists.

“The way I learned it, as an applied economist, is that productivity is necessary, but not sufficient,” said Melinda Smale, a professor of international development at Michigan State. Someone has to grow the food to produce the bare minimum to feed people. “And in a lot of the places I work, that is a real problem,” she said. But that’s not sufficient: You also need the markets, the distribution, the governance, perhaps the egalitarian class structure, so that each person gets that bare minimum.

Since I quoted Conway saying that we have enough food for everyone, I should now also include his next sentence: “But of course, food is not divided in this way (nor is income), and it is unrealistic to expect it will happen in the near, or even distant, future.”

Oh yeah. There’s that.

If anyone knew how to flip the democracy switch on, and the inequality switch off, that would obviously be the first step. But those are tough, slow problems. On the other hand, we do know how to increase farm yields.

“You can’t stop spending on agricultural research and rural roads until we are all democracies — that just won’t work,” said Mark Rosegrant, a director at the International Food Policy Research Institute. It’s worth noting that China, the country that’s done best in the past 50 years decreasing poverty and hunger, is not a democracy, he said.

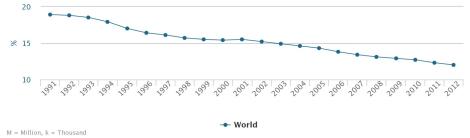

FAOGetting better: Prevalence of undernourishment – three-years average. Click to embiggen.

Good agriculture can help with the project of achieving good politics. The primary reason to increase yields, Rosegrant said, is to combat poverty by providing more income to farmers. The fact that yields increase the food supply and lower prices for everyone is secondary.

But wait a second, I said: How can you have higher yield producing lower food prices and higher income for farmers at the same time?

Things generally balance out in favor of the farmer, Rosegrant said. Say you are a small rice farmer in India. Perhaps a government agronomist teaches you about new agricultural techniques, or new wells allow you to better control irrigation. The higher yields from your farm might increase your profits by 30 percent, while reducing food prices by 15 percent. That’s a fairly typical scenario, he said.

So people are absolutely right to say that — if you are concerned about hunger — farm yields are less important than politics and poverty. But it’s not an either-or proposition: A large body of evidence suggests that improving agriculture is a powerful way to reduce poverty.

This leads us to several other questions. In subsequent posts I’ll be asking, what type of agriculture investments best combat poverty? Or should the money be going to something entirely different, like education or healthcare? And some of you may be asking, what does poverty have to do with the environment? Couldn’t the effort to help the poor produce more food exacerbate the fundamental problem of overpopulation? I’ll be trying to take all that on.