Josh Goldman once spent three years looking for a fish.

No, it wasn’t a Monty Python sketch. Goldman, who had spent years farming striped bass and, before that, tilapia, wanted a better species of fish — one that didn’t have the bass’ problems, like short fertile periods or a tendency to get stressed when moved from tank to tank. He also wanted one with the health benefits — namely, heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids — of a predatory species, but without the enormous inputs required to raise big, carnivorous fish such as salmon or tuna.

The stakes, globally, are high. With wild fish stocks collapsing — the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 32 percent of the world’s ocean fisheries are depleted or overfished, and another 52 percent will become so if they’re pushed beyond present levels — many people see aquaculture as the best hope for easing pressure on the oceans while still helping meet the growing global demand for fish protein.

But those familiar with the perils of industrial agriculture on land shouldn’t be surprised that fish farming — currently one of the fastest-growing food industries in the world — comes with a whole school (ouch) of downsides. Fish can escape, spreading disease and screwing up local ecosystems. As with other livestock, concentrating too much of their poop in one place creates big problems. And while farmers such as Will Allen have shown that tilapia and other fish can be useful parts of closed food systems, most operations, especially those that produce coveted predator fish, require tons of outside feed — much of it fish protein that humans could eat, plus industrially farmed grains — to produce their filets.

Australis

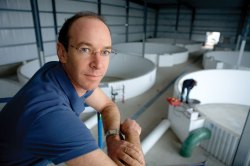

Goldman’s company, Australis Aquaculture, is trying to prove that it doesn’t have to be that way. The company has trademarked the taglines “The Better Fish,” “The Sustainable Seabass,” and even, “Smart Aquaculture.” It’s gained a lot of recognition from environmental groups, everybody from the Blue Ocean Institute to the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch, as a clear step in the right direction. But the Australis story also highlights some of the big questions in the world of sustainable aquaculture that remain unanswered.

Back to that three-year fishing trip. After procuring and testing some 40 species of fish from around the world, Goldman finally settled on his winner: the barramundi, an Asian and Australian native known for sport-fishing and its popularity in Thai cuisine, but mainly unknown to Americans. Some eight years later, the fish is ubiquitous: You can find it cooked in fancy restaurants, swimming in Chinese markets around the country, or frozen, in zip-top bags, from Costco, Safeway, or Whole Foods. It’s been recommended by Dr. Oz and featured by celebrity chefs. Need a recipe? Check out recent issues of O Magazine or Runner’s World.

Goldman chose barramundi because their personalities are “tame, gregarious, and kind of patient” — well-suited to life in tanks. And, unlike most fish, which only obtain omega-3s from the plankton and algae — or other fish — that they eat, barramundi can actually synthesize them on their own. “They spend a lot of their early life cycle in freshwater, so they’re not exposed to the long-chain fatty acids,” explains Goldman. “They actually develop the ability to build omega-3s without necessarily having to consume them.”

This is key to the barramundi’s claims to sustainability. One pound of farmed bluefin tuna can require as much as 20 pounds of wild fish as feed; for farmed salmon, the ratio is often well above 3 to 1. That means a host of problems: depleting the biomass of the oceans at a faster pace, decimating so-called “forage fish” that serve as a staple in poor countries, and, since some estimates say aquaculture demands will outpace fish meal production within decades, undermining the industry itself.

“Everybody on the marine side is really focused on reducing fish meal and oil” in fish feed, says Goldman. “There’s a consensus on that — that it’s really, really important.”

Australis has brought its fish-in-to-fish-out ratio down to about 1 to 1, counting all the fish that go into making the concentrated fish oils the barramundi are fed before harvest. This is very low for a predator fish — and the company is continually on the lookout for ways to bring it down still further — but it can’t match the efficiency of plant-eaters like grass carp or tilapia, which make up the bulk of global aquaculture. “We raise animals to convert things we can’t eat, like grass, into things we can,” points out marine scientist Callum Roberts in his book, The Ocean of Life. “But this simple logic doesn’t apply to aquaculture of predatory fish.”

The difference, says Goldman, is that “you don’t think of those low-trophic fish as high culinary value species. Nor do they offer a lot of omega-3s.” Still, if you’re looking to aquaculture as a way to feed the world, such ratios aren’t good enough. And Australis, like many fish farms, still relies on lots of terrestrial feed: canola, soy, concentrated corn protein.

A lot of the fish we farm commercially were chosen because they’re market winners, not because they’re well-suited to farming; raising ocean predators like salmon and tuna is sometimes compared to farming tigers. The lesson of barramundi seems to be: Choose a more sustainable fish, and then build the market for it. (Some argue this is a good reason to genetically engineer farmed fish, but Goldman vehemently disagrees: “There’s so much opportunity just to understand what nature has been up to in the natural evolution of these species.”)

Australis’ flagship facility in Massachusetts, with its green Seafood Watch rating, is considered a model for dealing with the risks of aquaculture. The barramundi are raised in an entirely closed system, so there’s no chance of them escaping. The fish move through five stages as they grow, each with a filtration system to remove fecal matter. The water is recycled and manure is stored in a tank, then given away twice a year to local farmers who use it as fertilizer. “When you do the math, what leaves the farm ends up being equivalent to just about three to four households of waste for quite a large farm,” says Goldman.

Still, there’s the question of scalability: The Massachusetts facility, with all its advancements, doesn’t produce cheap fish. Its barramundi are the ones that end up on white tablecloths or shipped live at premium prices. The Australis barramundi you might buy at Costco likely comes from the company’s facility in Vietnam, where the fish start off in closed tanks but live the latter two-thirds of their lives in offshore marine cages.

This, says Goldman, is by far the more scalable model. He sees marine farming as a way to increase the areas where food can be produced, especially when implemented in relatively nutrient-poor tropical seas. The facility in Vietnam has yet to be officially rated, but since the hybrid model largely eliminates escapes, Goldman hopes to secure Seafood Watch’s first green light for offshore cages. “The reason that people are opposed to cages is not, fundamentally, the cage: The reason is disease interaction, escape, genetic interaction, etc. So if you can address those things, which we have, then you’re deserving of the green rating.”

Right now, every innovation in sustainable aquaculture is desperately important. According to the FAO, humans may be eating more farmed fish than wild as soon as 2015. Aquaculture, in fact, is the fastest-growing food industry in the world. “I think there’s a consensus that aquaculture has a major role to play in food security — especially given climate and population challenges,” says Goldman. That means those unanswered questions need to get answered — and fast.