A bout of food poisoning is a memorable and vomitous experience. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 48 million Americans each year are sickened by bad food and 3,000 of them die. In the case of food-borne illness outbreaks, like the one we saw this fall in peanuts, it can take weeks and even months to track down the culprit. We’d love for causes to be clear, but of course it’s not that easy.

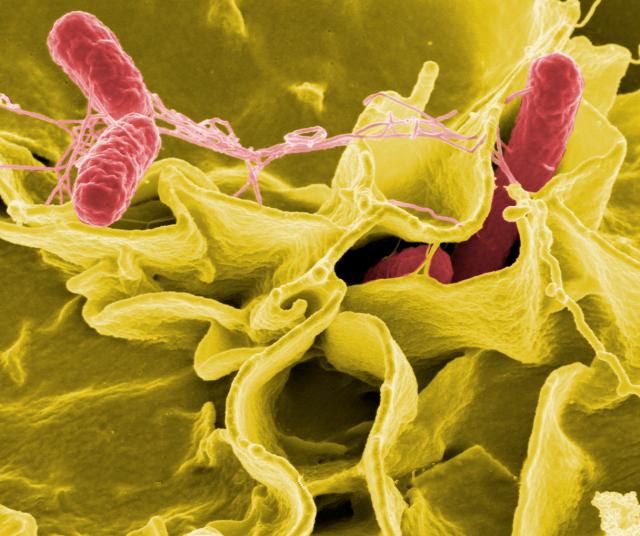

NIAIDPlease stay out of my peanut butter, salmonella.

The Columbia Journalism Review has a long feature on why it’s so hard for scientists and reporters to identify the sources of food-borne illnesses.

The epidemiology of foodborne disease is complicated; there are numerous barriers to definitively linking sick people in multiple states to the same pathogen and a common food product. One of the biggest hurdles is that foodborne illnesses are severely underreported. For every case of Salmonella that is reported, the CDC estimates that some 29 are not. …

Detecting and solving foodborne-illness outbreaks relies heavily on the capacity and expertise of state and local health departments, which have been hit hard by budget cuts and are often tracking multiple outbreaks or small clusters of disease at once. …

Even when dealing with confirmed illnesses, it’s difficult to definitively link them to a food product. Health officials use food-history questionnaires to help identify foods that sick people have in common, but it’s not easy to recall what you had for lunch three days ago, down to the ingredient. Cracking the cases can take some time.

It’s not just our bad food memories at play here, of course — industrial farming practices have done wonders to mix our spinach with our pig feces.

But now the Food and Drug Administration is proposing big, new food-safety rules, especially in some key farming states where our food has gotten pretty gross in recent years. The Los Angeles Times reports that the new rules are aimed at transforming the FDA “into an agency that prevents contamination, not one that merely investigates outbreaks”:

The rules, drafted with an eye toward strict standards in California and some other states, enable the implementation of the landmark Food Safety Modernization Act that President Obama signed two years ago in response to a string of deadly outbreaks of illness from contaminated spinach, eggs, peanut butter and imported produce.

The first proposed rule would require domestic and overseas producers of food sold in the U.S. to craft a plan to prevent and deal with contamination of their products. The plans would be open to federal audits. The second rule would address contamination of fruit and vegetables during harvesting. …

The third rule, which has yet to be issued, would establish how food importers would verify that the products they bring in meet U.S. standards. …

The FDA said developing the complex new rules took time as it consulted “consumers, government, industry, researchers and many others,” and “studied, among many other sources, the California leafy greens marketing agreement.” Additional rules will “follow soon,” the agency said.

USA Today reports that “[f]ood safety advocates and the food industry, who have been waiting for the rules with mounting frustration, are thrilled.”

But the frustrated waiting isn’t over yet: There will be a four-month period for public comment before the rules are finalized, and then at least 26 months before farms have to comply. That sounds like a glass of ginger ale for a food industry sick with E. coli.