The rising price of food isn’t the only thing driving the revolutionary fervor from Tunisia to Turkey to Brazil. The bad economy was surely a principal factor (remember that Adel Khazri shouted “This is Tunisia, this is unemployment,” as he burned). There was the effect of new social media technology. And then there was that tyranny thing that people seemed to dislike.

But food scarcity is different, because it looks as if it’s going to stick around even as the economy improves. And unless we do something about it, the riots and protests will spread.

As Motherboard writer Brian Merchant put it:

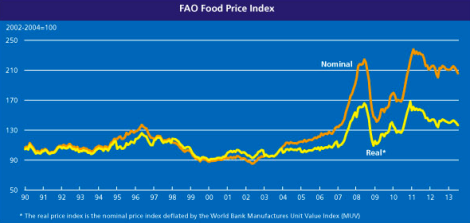

Two years ago, the New England Complex Systems Institute published a famous paper that sussed out the mathematical correlation between food prices and unrest: Every time food prices breached a certain threshold, riots broke out worldwide.

We’ve been bouncing around that threshold — 210 on the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization index — for years now.

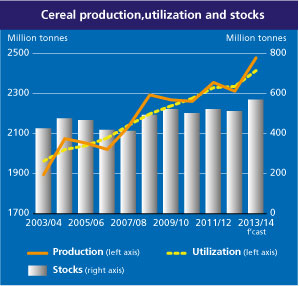

There’s a bit of a downward trend currently; farmers are planting more. We’re on pace to set a new world record for wheat production this year, and, as a result, prices are dropping a bit. But consumption is rising almost as quickly as production. As you can see from the FAO numbers, prices spiked in 2008, then never really settled back down to pre-recession levels.

The problem is that we have more people, eating more food, every year, and farm yields that are stagnating. Add to that the forecast for increased droughts and severe weather, and you have a recipe for rising food prices.

Egypt is especially vulnerable to rising prices because its population is booming and it relies heavily on imports. In recent years Egypt has converted many of its small farms that grow food for local consumption into larger farms that grow cash crops for export. In a report on this trend by the Center for Investigative Reporting, engineer Mamdouh Hamza quoted an Egyptian proverb:

If you don’t eat with your hand in the farm to produce your food, you will not be able to think with your own brain; somebody will think for you. Who — who will feed you?

That’s more than a rhetorical question now: Egypt was the world’s biggest wheat buyer, but the country stopped imports in February as it started running low on cash.

If we want a more prosperous, stable world, we’re going to have to either regulate to decrease population (not likely, when we can’t even pass a carbon tax), or begin working harder and smarter with food. We’ll have to invest in methods to increase food production. We’ll have to stop wasting so much, and probably feed less to animals (and internal combustion engines). We’ll have to do it sustainably, so we’re not robbing our children to feed ourselves. And communities will have to bring more food production closer to home, so they’re less vulnerable to the swings of a global commodity market.

Advocates of various political stripes tend to stress one of these points and leave out the rest. The challenge is to meet all of these objectives at once. We can do it, and I think we can make the world more beautiful and equitable in the process, if we’re willing to drop ideology and consider all the options before us.

P.S. Kudos to David Frum, who predicted this mess back in 2012.