There’s a Paul McCartney quote popular with veg-heads: “If slaughterhouses had glass walls, everyone would be a vegetarian.” It may not be quite as simple as all that, but he’s definitely got a point.

There’s a Paul McCartney quote popular with veg-heads: “If slaughterhouses had glass walls, everyone would be a vegetarian.” It may not be quite as simple as all that, but he’s definitely got a point.

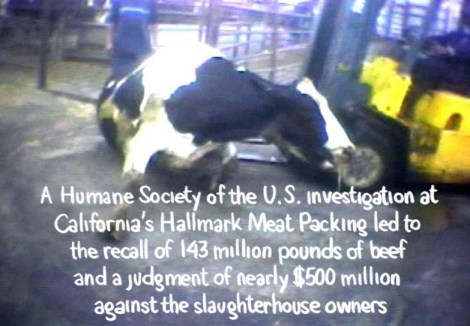

For a little over 10 years, groups such as Mercy for Animals, the Humane Society of the United States, and Compassion Over Killing have conducted undercover investigations into abuses and rules violations on factory farms, and publicized what they’ve documented to lobby for change.

It’s worked: Individual campaigns have resulted in business closures, criminal charges, and even broader changes in social behavior. That has got Big Animal Ag scared.

So it has done what Big Ag does best: crafted legislation and lobbied for it. State farm-protection laws, or “ag-gags,” as The New York Times‘ Mark Bittman lovingly called them, come in many different forms, mixing various combinations of restrictions on undercover filming and activist access to farms and slaughterhouses. Some of the laws give a nod to the value of whistleblowers but require that damning footage be handed over to law enforcement within a day or two, immediately blowing the cover of investigations that would typically last from two to six weeks.

Though they’re now enjoying a flurry of attention, these laws aren’t actually new.

“These ag-gag bills are really an extension of a pattern of conduct by these corporations that began more than 20 years ago,” says Will Potter, journalist and author of Green is the New Red.

Kansas, Montana, and North Dakota each passed less restrictive versions of these laws between 1990 and 1991, when the Animal Liberation Front was running around in balaclavas, freeing animals on fur farms, and smashing butcher shops. In 1992, Congress passed the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, boosting penalties for these crimes at the federal level.

But after Sept. 11, 2001, radical activists softened their tactics. “People thought, ‘We’re going to be conflated with terrorists and we need to change our activism,'” says activist Andy Stepanian.

At the same time, the web made it easier than ever to spread images and video. Undercover investigations by individuals and nonprofit animal advocacy organizations, often done in conjunction with local law enforcement, became a softer but incredibly effective form of action. Over the past decade, these investigations have uncovered inhumane, dangerous, and illegal practices, as well as heaps of environmental pollution.

“Now, the biggest threat facing Big Ag isn’t that activists are breaking windows — it’s that they’re creating them,” Potter writes at his Green is the New Red site.

During the height of these investigations, in 2006, Congress gave the Animal Enterprise Protection Act a shot of hormones, beefing it up to the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (AETA). Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio) was the lone dissenter in Congress, saying the law was “written in such a way as to have a chilling effect on the exercise of the constitutional rights of protest.” The act added new “terrorism”-related penalties for people who caused property damage to an animal business, or whose speech is considered to have the potential to incite violence. Several activists, including Stepanian, were convicted under the law, which still stands. Their offense: They made a website.

Potter calls this series of legal escalations “a foundation to really push the limits of the law in an attempt to go after whistleblowers.”

So OK, you say, but so what? There are a lot of terrible laws. And you’re right!

But the AETA, along with a slew of new ag-gag laws passed and proposed around the country, aren’t really about just meat, animals, or agriculture — they’re about corporations protecting business interests at all costs. They all trace back to model legislation crafted by the American Legislative Exchange Council, whose core value is promoting free-market ideas. And while ag-gags don’t expressly label undercover documentarians as terrorists, there’s more than one member of Congress who has no problem conflating undercover video with unrelated arsons and “economic terrorism.”

And as scary as this crackdown might be, it’s only indicative of what we might expect next.

“They’re taking the same kind of framework for that legislation and then applying it to whatever issue is being targeted by activists that affects business interests,” says Stepanian.

Indeed, some of the proposed laws include provisions that would protect any kind of manufacturing. That means they would protect fracking, mountaintop-removal mining, and other fossil fuel operations in the same way, criminalizing whistleblowers across the board.

This week we’ll look at the full reach and scope of these laws, hear from undercover investigators, and talk to activists who are fighting these bills but also see a silver lining.

The past 10 years have proven that Paul McCartney is right about the slaughterhouses. We’ve seen changes in our food system because investigators, activists, and whistleblowers have made those walls more transparent. There’s just no telling yet if they’ll stay that way.