John Norquist. (Photo by Congress for the New Urbanism.)

Excerpted from a longer interview in Next American City.

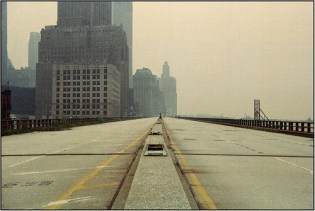

One of John Norquist’s best-known achievements as mayor of Milwaukee — an office he held from 1988 to 2004 — was demolishing the Park East Freeway, a 1960s-era expressway that restricted access to the city’s downtown. Today, he is CEO of the Congress for the New Urbanism, an organization that promotes urban highway removal and walkable, mixed-use urban development.

Norquist, who is also author of The Wealth of Cities, an argument for using the free market to achieve urbanist goals, will be one of the featured speakers at the Congress’ 20th annual gathering in West Palm Beach, Fla., this May. Here, he discusses urban highway removal — where it’s been done, where it will happen next, and why we as a nation must overcome our obsession with reducing congestion.

Q. As local leaders around the country are now seriously considering highway removal in some form or another, how do you suggest convincing concerned residents that such a move is right for them and their city?

A. Well, you have to change the discussion from pure traffic count comparison to traffic distribution. A robust street grid, with lots of connections, will distribute traffic much better than a few large freeways.

For example, when the Embarcadero Freeway, a double-deck freeway [in San Francisco], was torn down, a majority of the trips — according to a study by the city of San Francisco — got shorter and faster because of the increased connectivity. With the freeway, there were a lot of trips where you overshot your destination and had to come back. It also attracted trips that didn’t add any value to the neighborhood: People going from Oakland to Marin County were cutting through San Francisco. When the freeway was torn down and replaced by a boulevard, it suddenly didn’t look so attractive to go that way, and [drivers] found a different way to get to Marin Country or, in some cases, didn’t make the trip.

Q. What is the best way to fund urban highway removal?

A. A lot of freeways are headed beyond their design life, so they have to be rebuilt. You can’t just resurface them again. It’s cheaper to just tear it down and replace it with a surface street, so you win the cost argument by comparing it with rebuilding the freeway.

As far as other funds that are available, you can try for some of the TIGER grants … But I think the biggest single way to finance these things is to compare them with rebuilding the existing structure. In the case of Milwaukee, it cost about a third as much to tear it down as it would’ve been to rebuild it.

Q. What are some of the highway removal projects around the country that you consider particularly admirable?

A. New York’s West Side Highway was closed in 1975. It fell down once in ’73, and they repaired it, and it fell down again in ’75. At the end of its 40-year design life, it fell down right on schedule. And it was just really expensive, and politically unpopular, to rebuild it … The result of the West Side Highway coming down was [that] it really helped the rebirth of the real estate market in Chelsea, Tribeca, Battery Park City.

In Portland, the riverfront section of the expressway was removed and there was a huge property value increase. People could see the [Willamette] River, and without the freeway in the way, that made a huge difference.

And then in Seoul, South Korea, is the most spectacular one of all: They took out a freeway with over 150,000 cars a day and replaced it with two moving lanes on each side of a river, which they restored. And it works just fine because they have a really rich street grid in Seoul.

Basically, freeways don’t belong in densely populated cities. They create more problems than they solve. They’re very expensive, so almost nobody’s building new ones. That tells you that they’re sort of doomed: When you’re not doing new ones, you’re going to eventually have to remove the old ones.

Q. What about some of the pending projects? Are there any that stick out in your mind?

A. I’d really, really love to see the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans reach a point where it can be removed. I think the neighborhood’s pretty well convinced that it’s a great idea. Two aldermembers are for it. There’s a third councilmember who’s still debating if it’s a good idea, and then the mayor has said favorable things about it. He’s not completely locked in yet, but there’s a good chance of the Claiborne coming down.

We’ve got to take care of some concerns, like the Port of New Orleans — they haven’t quite wrapped their mind around us yet as a good thing for them. There are a lot of truck movements that have to do with the port, and some of those trucks go on the Claiborne. But it’s only three miles long, and a multi-lane boulevard would be able to handle the traffic at almost the same speed — not quite as fast, but it might even work better in rush hour because it wouldn’t congest as much.

That’s one of the things about freeways: They tend to fail when you need them the most. They fill up, and then there’s no escaping. Once you’re on it, you just have to wait until they uncongest. Whereas when you’re on a surface street — like, say, Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C. — even though it’s a big road that carries a lot of traffic, it really doesn’t come to a complete standstill, because there are so many cross streets that, if the thing congests, then people go to a different street instead. They turn right, get off the street and go to Massachusetts Ave., or Wisconsin Ave., or one of the other streets.

Q. Despite underuse and pretty bad congestion on many urban freeways across the country, there’s still this strong, vocal element against removing freeways, people who still want them in their cities.

A. It is a hard sell, because it’s counterintuitive. So the average person hears that you want to tear down the Claiborne Expressway, and they go, “You want to do what? How could you be against that big road? Cars probably need it. Traffic needs it.” So you have a lot of explaining to do, and it takes years, sometimes, to get to the point where the public says, “Oh, yeah, maybe that isn’t such an idiotic idea after all.”

Q. Do you think that stems from a misunderstanding of highways and their effect, or is there something else at play there?

A. Everybody’s been sort of trained to believe that if you’ve got a traffic problem, all you have to do is make the pipe bigger, you know, make the road wider and that’ll solve the problem.

The Detroit metropolitan area is covered with freeways … More than any other place in the country, the Michigan DOT pretty much got its way. And they have solved the problem that they identified, which was congestion … So by creating a transportation system that encouraged people to leave town — the population of the city is about a third of what it was since 1950.

[Detroit] had 300 miles of streetcars at the end of the war. That’s all gone … The street grid has been cut up, so it’s hard to move around on the surface streets. [But] the stated goal was to battle congestion, and in Detroit, they did it. And there are side effects.

You could take care of congestion in New York in a similar way: If you eliminate the 700 miles of subway, eliminate the commuter trains, build the Cross-Manhattan Expressway, put the West Side Highway back in — build all the freeways that Robert Moses didn’t get around to building — you could probably solve the congestion problem in New York. Manhattan’s population would drop from 2 million down to half a million, and the city would become a really poor place instead of a rich place.

The point I’m making is that, since the postwar period, federal transportation policy has been focused on eliminating congestion, and that’s too narrow a goal. The goal ought to be: What adds value to society? What adds value to the economy? If you look at the richest places in America, they’re the most congested.