Just a few decades ago, California’s Inland Empire billed itself as “the Orange Empire” for the citrus orchards that fueled its primary industry. Today, many of those groves are gone, and so is the nickname. The landlocked region of 4 million people an hour east of Los Angeles now sprouts more enormous warehouses (a billion square feet of them) than fruit trees.

Forty percent of the nation’s consumer goods — iPhones, sneakers, and everything available from Amazon — spend time sitting on those warehouse shelves after coming off ships at nearby ports, awaiting delivery to stores and homes. What was once a mostly rural region finds itself struggling with a high poverty rate and growing population. Residents are plagued by tremendous traffic and air pollution, which recently earned the region an “F” from the American Lung Association.

Those environmental and health concerns will get much worse, advocates say, if the city of Moreno Valley — a town of 200,000 located in the heart of the Inland Empire — builds the largest warehouse project anywhere in the country.

Tom Thornsley is a 60-year-old urban planner who moved to Moreno Valley in 1998, just as the rural-to-warehouse transformation was beginning. He thought he had chosen wisely, settling in a gray, ranch-style home that sat near a wide-open space zoned for more homes, not warehouses. “I know better than to look at dirt and not check what it would be,” he says.

But after a developer proposed a project in 2012, city officials rezoned that dirt patch next to Thornsley’s house to make it home to one of the world’s largest warehouse complexes.

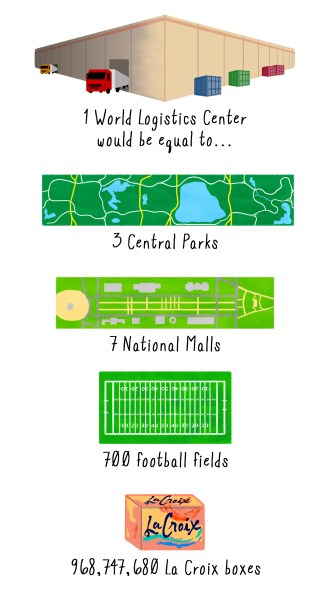

Click to embiggen. Grist / Amelia Bates

The World Logistics Center, planned by a company called Highland Fairview, would be the largest such facility in the country, covering 2,610 acres — the size of 700 football fields. It would be more than 25 times bigger than the largest warehouse in the United States, a 98-acre hangar operated in Washington by the airplane manufacturer Boeing.

As a planner, Thornsley doesn’t have a problem with industrial development. He’s worked on commercial buildings since 1989. But the environmental costs of the World Logistics Center are too much for his community, he says, so he’s become a leader in the effort to stop it — an effort that might hinge on next month’s special city council election.

The World Logistics Center, which is now known locally by the acronym “WLC,” has turned Moreno Valley politics into a bloodsport. Community organizers and environmental groups have fought — in both city hall and the courtroom — to protect residents from the pollution it would cause and save protected species like peregrine falcons and California golden eagles that live in the nearby San Jacinto Wildlife Area.

Once built, warehouses don’t pollute the way that factories and power plants do. But a project the size of the WLC would be a magnet for truck traffic, spewing exhaust on 69,000 estimated daily vehicle* trips in and out of the complex. In a struggling region, though, the lure of jobs has proven difficult to overcome, despite the public health and quality of life concerns.

“That’s why people are pressing so hard now,” Thornsley says, “to get somebody elected who’s not going to be, in essence, another developer’s puppet.”

Southern California’s two ports are among the deepest on the West Coast, allowing massive ships to dock at Los Angeles and Long Beach. More than $360 billion worth of goods from production centers in the Asian Pacific were offloaded there in 2014. Warehouses originally crowded around the ports, until Los Angeles could no longer contain the growth.

Demand for more space at cheaper rates pushed development farther east, and the Inland Empire became the hidden purgatory between production and consumption. Only the Philadelphia area currently has more warehouse space, but projects like the WLC would leave that East Coast hub in the dust. Over the past five years, the logistics industry has delivered a quarter of the new jobs in the region.

But the economic boom carries a heavy environmental toll: Diesel trucks zip along the Inland Empire’s roads, carrying cargo to customers and piping particulates into the air. Winds rushing in from the ocean blow added pollution from L.A. and Orange County, which accumulates in the basin bounded to the north and east by mountains.

That makes the Inland Empire one of the unhealthiest places to live in the country. Air pollution leads to higher risk of heart disease, asthma, bronchitis, cancer, and more. The South Coast Air Basin — which encompasses parts of Orange, Riverside, San Bernadino, and Los Angeles counties — exceeds federal and state requirements for lead and small particulate matter, which can lodge in the lungs. San Bernardino and Riverside counties, which make up the Inland Empire, ranked first and second, respectively, among the top 25 most ozone-polluted counties in the American Lung Association’s 2016 air quality report.

Low-income neighborhoods and communities of color bear the brunt of this pollution, because they’re often situated near freeways or become sites for warehouses. Moreno Valley’s population is 18 percent African-American and about 54 percent Latino.

In a community where nearly 20 percent of people live in poverty, it’s easy for a big developer to gain support for a project like the World Logistics Center — especially with the promise of 20,000 permanent jobs and $2.5 billion a year added to the local economy. But the downside includes 14,000 added diesel truck trips per day and a 44 percent increase in the city’s yearly greenhouse gas emissions.

Many warehouse jobs are also low wage, temporary, and unsafe. The facilities rack up a plethora of safety violations, according to California health and safety inspectors, and workers report high levels of injury and illness.

Many residents believe “this is the best I can get,” explains Sheheryar Kaaosji, coexecutive director of the Warehouse Workers Resource Center, which advocates for employee rights. “That’s what it comes down to.”

Tom Thornsley, who has decades of experience in urban planning, says development decisions are all about weighing the pros and cons. When a project is proposed, environmental risk assessments let you know how harmful the development could be, which tells you whether it’s worth it and if you can do anything to mitigate the harm.

Ultimately, he says, if a project’s benefits outweigh its problems, “You just decide you can live with it.” In the case of the World Logistics Center, he can’t. An analysis of health impacts prepared for the developer acknowledges the potential for increased incidences of asthma, heart disease, and premature deaths.

Thornsley’s dismay over another warehouse project — for the shoe brand Skechers, which opened in 2011 and brought a net job loss — pushed him to join up with Residents for a Livable Moreno Valley, a community group created to combat rampant warehouse development.

The group has found itself battling a formidable nemesis in the person of Highland Fairview’s charismatic CEO, Iddo Benzeevi. During the protracted WLC fight, Benzeevi has become a folk hero to some Moreno Valley residents. When the city council narrowly approved the project in August 2015, residents swayed by the promise of jobs chanted “Iddo, Iddo, Iddo.”

“They think he walks on water,” Thornsley says. “I honestly couldn’t tell you why they find him to be so adorable.”

In public council meetings ahead of the vote, many residents lauded the project as a game changer for the city. “These are not jobs that are just back and hands, they’re technical jobs, they’re jobs that are going to be able to support a family,” said one woman who has lived in Moreno Valley for more than 30 years.

“Most people recognize Moreno Valley as one of three things: crime, corruption, or unemployment,” says resident Leo Gonzalez in a series of 2015 YouTube videos supporting the WLC. “I believe we have the ability to change all that.”

In addition to currying favor with residents, Benzeevi skillfully navigated California’s arcane political and environmental laws. Thanks to a 2014 California Supreme Court decision involving Walmart, ballot initiatives that garner enough residents’ signatures can escape the state’s Environmental Quality Act review process. Benzeevi took full advantage of that for the WLC.

Iddo Benzeevi (Highland Fairview Community)

Meanwhile, Thornsley’s group pushed back. Residents for a Livable Moreno Valley filed lawsuits against the project, which has also faced separate legal challenges from the regional South Coast Air Quality Management District, Riverside County and its transportation commission, and a roster of environmental groups including EarthJustice, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Coalition for Clean Air.

“We already have among the dirtiest air in the nation,” says George Hague, a volunteer for the local Sierra Club chapter. “We keep trying to clean it up, but projects like this put us back.”

Benzeevi disputes this, arguing that the benefits of job creation would outweigh the environmental impacts. “There is no better solution to reducing impacts to the environment than creating jobs where people live while utilizing the best available and viable clean technologies,” Benzeevi told Grist via an email from his public relations department. “This is precisely what the WLC does.”

Benzeevi notes that Moreno Valley is requiring Highland Fairview to ensure that diesel trucks servicing the WLC meet a 2010 federal government standard for clean diesel. To which Hague counters: “They’re cleaner, but they’re not clean.”

With options running out for WLC opponents, the special June 6 city council election to replace a single vacated seat represents a longshot chance to block the megawarehouse project, by putting an opponent on the board who can help overturn previous approvals. The council is now deadlocked 2-2.

The open seat was previously held by Moreno Valley’s new mayor, Yxstian Gutierrez. A supporter of the World Logistics Center, Gutierrez won just under a third of the mayoral vote, but that was enough in a multi-candidate race. Benzeevi spent more than $160,000 to help his campaign.

Highland Fairview is now backing a preferred candidate for Gutierrez’s open council seat, pouring tens of thousands into canvassing for his campaign through the Benzeevi-sponsored Committee for Ethics and Accountability in Government. WLC opponents are pinning their hopes on the three remaining candidates — one in particular has been an outspoken WLC opponent — who face long odds of winning.

Whatever the election outcome, development in the Inland Empire shows no signs of slowing in the short term. But the environmental and health impacts of the logistics industry are starting to spur more awareness of the costs of warehouse growth.

The California Air Resources Board voted in March to relocate its research facility to the Inland Empire’s Riverside County, which could potentially offer a more comprehensive understanding of the region’s poor environmental quality. And a bill in the state assembly is challenging the lack of environmental review in the initiative process — the very rule that allowed Benzeevi to push his megawarehouse project through local government.

“We have such a disengaged citizenry — most of the people don’t understand the connection of the trucks to city hall,” says Kathleen Dale, a retired urban planner with the Residents for a Livable Moreno Valley group. “When you talk to people, this is a concern of theirs, but they’re not expressing it by going to the polls.”

*Correction, June 1, 2017: This story was initially unclear that the estimated 69,000 daily trips in and out of the World Logistics Center would include all vehicles, not just trucks. (Return to the corrected sentence).