UPDATE:Â

Whether a pair of gold leaf antlers or re-purposed industrial light fixtures, DIY projects have become a non-negotiable feature of any Zooey Deschanel-aspirant’s apartment. And Etsy, the online craft and vintage goods bazaar, has made those goods clickably easy to acquire. As a result, the site — now 1.3 million sellers strong — dominates the handmade market, raising the question: What happens when a company built for a marginal market goes mainstream?

When it was first launched into beta in 2005, Etsy gave independent crafters the freedom to apply for their own online “stores,” while providing a major boost in traffic.

Ten years later, Etsy has done enormously well for itself. The company model is essentially the same as it was in 2005 — its sellers pay a few dimes, post their items, and wait for the sales to come — but bigger. Much, much bigger. To manage its 26 million items for sale, Etsy employs 655 people in nine offices in major cities across the globe.

Craft lovers in nearly every country in the world, in the meantime, are buying their hand-sewn stuffed lambs and bronzed feather pins on Etsy en masse. The website is the fifth-most visited marketplace site in the U.S., after Amazon, eBay, Walmart, and Best Buy. In 2013, Etsy raked in gross merchandise sales amounting to $1.35 billion. And Etsy’s very existence has increased access to handmade goods around the world, and provided a tool for artisans to sell on a global market.

In 2012, the company became a certified B Corporation, an assessment given by an outside nonprofit to for-profit companies measuring transparency and social and environmental performance. A “B Impact Report” measures a company’s overall governance, workers’ rights, community involvement, and environmental impact. Out of a score of 200, Etsy earned a 105, a full 25 points higher than the median score.

Etsy, however, is fundamentally a micro-gig company — a web space built for people to find work doing small tasks, selling homemade goods, or pawning personal services. Participating in the gig economy, whether as a gigger or a gig-receiver, is a way to rely less on large corporations. But with so many people competing for the same gigs, many people struggle to make living wage. In fact, some gig companies are being sued within an inch of their lives because of their failure to protect workers’ rights — as the companies themselves grow and profit enormously.

The mega-seller has attempted to distance itself from the Ubers and TaskRabbits of the world by passing off its eponymous model as unique. But if you look at how Etsy functions, you’ll find a perfect microcosm of all the problems of a gig economy.

In order to accommodate its ever-widening girth, Etsy has loosened the seams of a number of company policies. In 2013, Etsy changed its policies to allow shop owners to scale the size of shops, hire outside help, and partner with manufacturers. One of the most controversial changes was allowing manufacturers to sell machine-made items on the site — without clearly separating those items from those that were artistan-made.

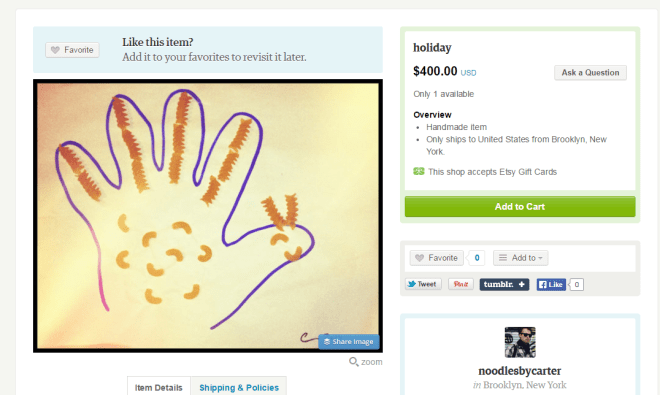

Opening a shop requires no membership fees, and only 20 cents to list one item for four months. You can literally open a shop selling elbow macaroni glued to scrap paper for $400, spending only two dimes per noodle-emblazoned sheet — no questions asked.

On Etsy, a mass-made-in-China bracelet is sold next to one that was painstakingly hand-welded in a studio apartment in Portland — and the former tends to be a fraction of the cost of the latter. Some crafters see this as a problem, others don’t — like artist and writer Nicole Burisch, who is currently co-editing the book, From Craftivism to Craftwashing: The Politics of Craft in the Global Economy. I spoke with Burisch about the practice of “craftwashing:” when products are branded to appear handcrafted in order to conceal their factory origins.

Craftwashing can obscure how goods are really made, but, Burisch told me: “The distinction between what’s handmade and what’s manufactured is more complicated. A mug that’s produced in China and shipped back to the U.S. still had someone’s hands on it.”

What role does Etsy play in craftwashing? “Etsy is a platform for selling stuff, and it has adapted to the way the crafts market has evolved in the past few years,” Burisch said. “You don’t know how [Etsy sellers] are firing their kilns, where their supplies come from, and where they’re getting their tools. There’s a lot of nuance between what’s considered handmade and what’s not.”

Still, the introduction of mass-made faux-artisanal items to the Etsy marketplace has put many of the site’s artists on edge. In a recent article for Wired, long-time crafter and blogger Grace Dobush announced that she had shut down her Etsy account, which had been active since April 2006. With the adoption of mass-produced items, she claimed, Etsy has alienated crafters and — to get right down to it — lost its soul.

“The loss of quality control and lack of curation on Etsy is what has made it successful and so large,” Dobush told me. “But it’s less valuable for buyers. They’re left guessing if something is going to be worth it, whether something is legit.”

Clearly, Etsy has a PRÂ problem. Company executives are working hard to restore seller relationships by being more transparent about policy changes. Recently, Etsy responded to the widespread complaint of lack of curation by undergoing a site redesign that allows members to curate their own shop pages, in order to differentiate between artists and manufacturers.

Additionally, Etsy recently launched a “Craft Entrepreneurship Program,” providing business skills training in under-served communities in cities in the U.S. and U.K. In those cities, Etsy partners with local organizations, which then recruit students and teach them craft skills as well as business-growing techniques.

If you browse through Etsy’s blog, you’ll find 261 success stories of crafters who “quit their day jobs” to make art full-time. There currently isn’t any information stating how many Etsy shop owners are working full-time and making living wage. (UPDATE: An Etsy representative has informed us that 18 percent of Etsy sellers have made that their full-time, primary occupation.) But, as Dobush told me, “Those outlier stories, like the moms making millions on scarves and headbands, are like winning the lottery.”

And most of the small business owners who are making the corporation giant? Well, they’re staying small.

It’s not that being a successful business owner on Etsy is impossible — but it does require a significant amount of extra work. One current shop owner, Abby Glassenberg, has over 5,000 “admirers” and over 4,000 sales at her shop, WhileSheNaps, where she sells sewing patterns and stuffed animals. For most Etsy shop owners, 4,000 sales on the site is a huge success. For Glassenberg, Etsy is working — 0r rather, she is making Etsy work for her. She wrote a blog post in November 2014 titled “Why I Still Love Etsy,” in which she explains how she disagrees with Etsy’s policies, but also still uses the site to her advantage. She writes:

All Etsy shops look the same. It’s not possible for sellers to customize their shops enough to convey their brand and unique identity.

Etsy is flooded with resellers. It’s very difficult for customers to distinguish between cheap factory made goods and things that are truly handmade. Very often the cheaper option wins. This is a long-standing issue and Etsy doesn’t seem to do anything about it.

It’s so easy to set up an Etsy shop that anyone can do it which means Etsy is full of poorly made goods and items that are woefully under-priced. This hurts everyone. It’s become incredibly challenging for customers to find the well-made, fairly priced items.

But:

Etsy is an incredibly effective way for me to bring in new customers who have the potential of becoming repeat customers and loyal followers.

I spoke with Glassenberg about her complicated relationship with Etsy. She told me that, despite its pitfalls, Etsy provides enough traffic and increase in sales in addition to her standalone shop. To this seller, Etsy is purely a form of advertising — it’s a way to be found.

“When someone wants to make something — say, a teddy bear — where are they going to go?” Glassenberg tells me. “They’ll type in teddy bear pattern to Google, and Etsy is going to be the first to come up. As a business owner, I want mine to be the one that comes up first. Etsy makes up 40 percent of my pattern sales, and I’m not giving up 40 percent of my sales. I still want that.”

It’s true that Etsy’s craft market is saturated and extremely competitive, Glassenberg explains. So it’s up to the artist to create her own opportunities.

“Because Etsy sends my products to customers, I email each of them right after the sale,” says Glassenberg. “I tell them thank you, and I invite them to sign up for my newsletter. Then slowly over time they get to know me. Most likely, their next purchase will be from my stand alone website. It’s not just Etsy traffic. That’s how I get my own customers.”

For many DIYers, Etsy seems like the only option to get new eyes on their products. But as the company gets bigger and bigger, sellers’ welfare can come second to keeping up with worldwide demand. As Dobush told me, “Etsy needs their price points to be affordable, because people want deals, right? But the obvious pitfall of that economy is that someone is going to get the short-end of the stick — and it’s probably going to be the sellers.”