What we do with our dead can seem bizarre to outsiders. In a Tibetan tradition called sky burial, the deceased are cut into small pieces by a man known as the rogyapa, or “breaker of bodies,” and laid atop mountains to be picked apart by vultures. Later, the bones are collected and pulverized with flour and yak butter and fed to crows and hawks. Feeding your loved ones to the same birds who eat roadkill may seem morbid to those of us in the West, but in Tibet, it’s both sacrosanct (these birds are sacred in Buddhism) and practical (ever tried to dig a grave in frozen ground?).

Tibet isn’t the only place with seemingly odd customs: In Madagascar, the bodies of the deceased are exhumed and sprayed with wine and perfume every few years. In Ghana, people are buried in coffins that represent their lives, so a fisherman might spend eternity in a box shaped like a carp and a farmer may spend it in a six-foot cob of corn. These rituals sound weird or even ghastly to us, from half a world away, but are any as bizarre — or as damaging — as what we do with the dead in America?

For most people in this country, there are two options after death: You are buried or you are burned. The costs, both environmental and financial, are significant, but we accept these options because they are all that we know. One Seattle architect wants to change this, to develop a form of body disposal that will both cost little and actually improve the environment. But before we get to that, let’s look at the current state of death in America.

Most Americans, around 55 percent, are buried after they die. If you choose to be part of this silent majority, and if you opt for an open casket, your body will first be embalmed. This means that you will be drained of blood and injected with a delightful cocktail of formaldehyde, methanol, and other solvents. Pumped into your arteries, the embalming fluid acts as a preservative and slows decomposition by preventing the growth of bacteria that would naturally break down your cells. Basically, you’re pickled.

Next, a mortician will dress you (plastic underwear may be necessary for leaky bodies) and cover you with makeup to make you look as life-like as possible. This may have the opposite effect, turning you into a sort of fleshy mannequin. Someone will probably fix your hair.

Despite the mortician’s efforts, your body will eventually decompose (you aren’t made of styrofoam after all), but embalming makes it take years instead of weeks. Not only are you shot up with more preservatives than a McDonald’s hamburger, but your casket — which has a shell of either hardwood or metal — is then placed in a concrete container lined with plastic to prevent the land around your burial plot from sinking. This system is designed to be impenetrable, to keep out the elements that would naturally aid the body in decomposition, and it takes a lot of resources. Each year, over 30 million board feet of wood, 1.6 million tons of concrete, 750,000 gallons of embalming fluid, and 90,000 tons of steel are buried underground in the United States alone. You could construct a Golden Gate Bridge with that amount of steel, but we use it to store bodies.

For many people — especially those concerned about the environmental impact of burial — cremation is the greener option. But how green is it? Turns out, not very.

If you choose to be cremated, your body will be placed in pine box in a high-temperature oven. After a few hours at 1,400 to 1,800 degrees, what’s left is a coarse gray powder with lumps of bone. The environmental impact of this process is not minor. Most crematoria are fueled by gas (a finite resource), and while some facilities use filters or scrubbers to reduce pollutants, cremation still results in soot, carbon monoxide, and trace metals like mercury being released into the air. According to the Funeral Consumers Alliance (FCA), each cremation takes 28 gallons of fuel and releases of 540 pounds of carbon dioxide. Multiply this by the 912,000 bodies that are cremated every year in the U.S., and the FCA estimates that 246,240 tons of carbon dioxide are released into each year due to cremation, or the equivalent of 41,040 cars.

After cremation, your remains may be stored on a mantel, scattered on a beach, poured in an hourglass, shot into space, turned into diamonds, mixed in with paint, stowed in a drawer, tattooed on a body, buried in coral, turned into concrete, blown into glass, pressed into vinyl, dropped off a boat, worn as jewelry, stirred into wine, or any number of other things. In my family, the tradition is to pack your loved one’s ashes in double baggies and ship them to your children around the country. Or at least that’s what my grandmother did when my grandfather died, attaching a note to put him on top of the TV for better reception.

What your ashes cannot do is nourish life. Cremated remains are devoid of nutrients, and so your ashes are less likely to fertilize the ground they are scattered on than bird shit falling from the sky. You’re dust.

And none of this is cheap. The average cost of a burial is between $7,000 and $10,000, cremation is between $2,000 and $4,000, and death-care is a $20 billion a year industry, one notorious for preying on vulnerable consumers and increasingly controlled by a single entity called the Service Corporation International (SCI). SCI has been buying up competitors despite protests from Funeral Consumers Alliance, which petitioned the FTC to stop SCI from purchasing the nation’s second-largest funeral services company, Stewart Enterprises, in 2013.

“It’s alarming to think that a company with a long track record of abusing consumers at the worst times of their lives might get even bigger,” wrote Josh Slocum, FCA’s executive director, in a press release. “For at least 15 years, grieving families around the country have complained to us about the practices at SCI funeral homes and cemeteries. From lying about options in order to boost the funeral bill, to digging up graves to re-sell them to another unsuspecting family, to denying the legal rights of LGBT people to make funeral arrangements for their partners. You name it, we’ve heard it.”

Despite protests, the merger was granted by the FTC. SCI estimated in 2014 that the company controlled 16 percent of the market. Its annual revenue was over $2.9 billion.

There are a few other options for body disposal in America, but they are not without flaws. Always dreamed of burial at sea? Good luck. You can’t just hire a dingy and have your loved ones dump you overboard. At-sea burials are regulated by the EPA, and hiring a company to do it for you will cost over $10,000. There’s also “green” or “natural” burial, which means a body isn’t embalmed or entombed and is allowed to decompose naturally, but there aren’t that many sites that allow this in the U.S., and most of them are in rural areas. For the vast majority of Americans, the choices are conventional burial or cremation.

But Katrina Spade wants to change this.

Spade is the designer, architect, executive director, and sole employee of the Urban Death Project (UDP). She’s in her late 30s, short-haired and androgynous, and she lives with her girlfriend and two kids in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Spade hardly looks like someone obsessed with death, and she wasn’t until a few years ago when she saw how quickly her kids were growing up. For the first time, she realized that if they were going to grow up, she was going to grow old, and then she was going to die. “I started to wonder what would happen to my body when I died,” she says. “What would my family do with me?”

Spade seems in no danger of dying any time soon. Her eyes are almost shockingly bright and even though it’s winter in Seattle, she looks like she’s been in the sun. As The Stranger’s Branden Kiley wrote in a recent profile, Spade “radiates good health and optimism,” and has the look of an athlete — a distance runner, maybe, like someone who has never smoked a cigarette in her life. But Spade is obsessed with death, and she’s trying to reshape the way we deal with it.

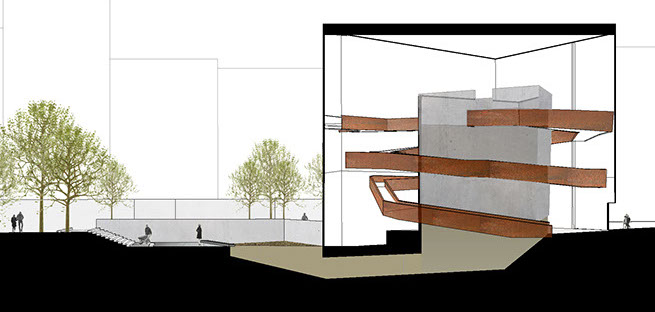

Specifically, Spade has made it her goal in life to give Americans another option for disposing of our bodies: human composting. Instead of being buried or burned when you die, your body could go to a “compost-based renewal facility.” The facility is essentially an enclosed building with a three-story “core” filled with organic material and encircled by a sloping walkway. During your funeral service, your body would be shrouded in linen and your friends and family would walk you to the top of the core and lay you within the soil.

Proposed Urban Death Project facility. Urban Death Project

“Bodies, our bodies,” Spade says, “will be laid into the ground and covered with wood chips. There would also be some other carbon materials that would help the process work a little more efficiently, like sawdust, which is very high-carbon, and possibly something like alfalfa straw.” The process of turning from human to soil is surprisingly quick. The UDP’s website says that within a few weeks of interment, “the body decomposes and turns into a nutrient-rich compost. The process is continuous — new bodies are laid into the system as finished compost is extracted below.”

There is precedent for this kind of burial, and it comes from agriculture. “Thank goodness,” Spade says. “I really don’t think I’m the appropriate person to create a brand new process but I do think that I’m the right person to take a process that’s been studied by agriculture and universities for a number of years now. The research is out there.”

Spade explains that when animals die on farms and can’t be butchered, their bodies are processed using “static mortality composting.” About 18 inches of wood chips are spread in a field, and the animal is laid on top and covered with another 18 inches of wood chips so it resembles a mulch pile. After a couple months, the animal is just … gone. With humans, Spade says, all that remains will be the artificial parts of us, “things like titanium hips and gold teeth.” Even your bones will disappear.

Of course, humans are not livestock and this process must be thoroughly tested before it’s put into practice. “One of the things we’re doing right now,” Spade says, “is starting to test human composting to understand exactly how long it takes, how much aeration you want, what’s the proper carbon mix.”

Testing is ongoing at Western Carolina University, a rural campus nestled deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in the Anthropology Department’s Forensic Osteology Research Station — more commonly known as a “body farm.” WCU is one of five universities with these sites in the country, and forensic students use them to study the stages of decomposition (that’s another thing you can do with your body — donate it to science). The site at WCU is also used for training cadaver dogs, and now, for measuring rates of decay for the Urban Death Project. Spade has visited, and described a recently laid-out body as “beautiful, though it didn’t quite register as human. It’s important to respect the body, but somewhere in the system we cease to be human. We can’t be human forever.”

After the project comes to fruition (and there’s a lot to be done besides just testing), Spade envisions using the first UDP as a prototype for communities all over the world. The same way you have a neighborhood library that reflects the local community, you’d have a neighborhood UDP. It would be staffed with funeral directors and function in many of same ways as the traditional funeral home — bodies would be prepared and interned at the site, and you could hold memorial services and come back later to visit, just as you would with a traditional graveyard.

Unlike a traditional graveyard, however, you could go home with your loved ones in the form of soil. You could then spread them in a garden or under a tree planted in their honor, and, Spade says, even public parks could be fertilized with the soil, so cities would be nourished by the people who lived in them.

The fact that this idea would work in cities is vital, says Spade, because urban cemeteries are running out of space. At the UDP facility bodies will be stacked with six to 10 feet of material separating them, so there’s no commingling during the decomposition process. After the initial breakdown, the remains would be mechanically aerated and mixed together, so, Spade says, the soil you take home is “basically your loved one and maybe a couple other loved ones.”

She understands this idea may be icky to some, but it’s an important part of her concept, the thing that differentiates it from other natural burials, which require extensive land. “There are a lot of people who wish I would make it so it was individual person by individual person,” she says, “and I’m sure I’ll continue to get pushback, but I’ll continue to be stubborn because I think it’s really important that we’re part of a larger ecosystem.”

The Urban Death Project exists only as an idea right now. There is no facility yet or even a name for one, plus the laws regarding human composting are unclear. (“It’s not illegal, but someone would probably try to stop you,” Spade says, and a large part of this project will be legislative.)

But Spade has funding from donors as well as a fellowship paying her salary (a Kickstarter campaign is scheduled to launch March 30, and, yes, one of the rewards is a spot in the facility). She also has a board of directors and a host of volunteers who want to see this succeed, mostly because they would like an ecological and low-cost option for their own disposal. (Spade doesn’t have a definite price yet, but the UDP is a nonprofit and she mentions a sliding scale.) When asked what kind of people reach out to her, Spade says it’s some of what you would expect — gardeners, environmentalists, non-religious people for whom nature is as close as they get to spirituality — but it’s also people who just don’t like the idea of their bodies going to waste.

If Katrina Spade gets her way, human composting will someday be as normal as burial or cremation, and maybe, eventually, it will replace them both. It may sound odd now, but is draining the body and filling it with formaldehyde any less bizarre? We accept burial and cremation because they’re what we know, but maybe human composting is the greater option. It’s cheaper, more ecological, and it keeps the cycle going: You aren’t ashes. You aren’t dust. You’re earth.