Zachary Myers leads the way into his horse-barn-turned-workshop in Centerburg, Ohio, a little less than an hour’s drive northeast of Columbus. Inside, along with two vintage Allis-Chalmers Model G tractors, there are rows and shelves of antique black Singer and Union Special sewing machines, their colored spools unleashing trails of red, green, and navy thread. On the wall, hung neatly in rows among farm tools, are white paper patterns of pant legs. Bolts of sturdy striped and solid indigo fabric unfurl across worktables.

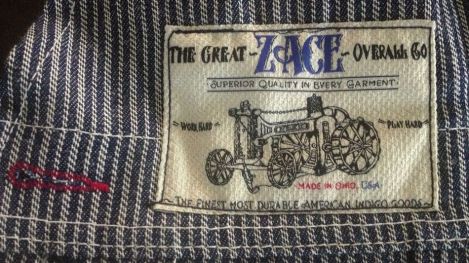

Myers, his arms painted with tattoos, sits at a sewing machine with a pair of overalls, puts a work boot to the pedal, and stitches on a label bearing a drawing of a sewing machine converted into a tractor, melding together his two passions. Emblazoned with his nickname, Zace, pronounced “Zackie,” it reads:

Zace The Great Overall Company

The Finest Most Durable American Indigo Goods

Myers, 36, is an organic farmer by day and an indie blue jean maker by night. He is a bold example of diversification, sustainability, and DIY innovation: Understanding the need for duds that can withstand hard agricultural labor, he created a line of durable work clothes for farmers. Working into the night, often by kerosene lamps, Myers, fueled by thick coffee and Ryan Adams, says his heroes are denim slingers such as Levi Strauss. He shows a sneak photo of himself bolting from the entrance of Ralph Lauren’s Rocky Mountain ranch.

“My generation is so fed up with the way our predecessors handled things in this country that we’re learning to craft things with our own hands,” he says. “And there’s nothing more American than denim.”

Zachary Myers

An Arizona native who rode bulls as a youth, Myers says devotion to denim began as a boy upon seeing pairs of Levi 501 and 505 unwashed, raw, jeans. “They were rugged, they were button-fly, and we couldn’t afford them,” he says.

When Myers was 19, he cobbled together a pair of gloves for snowboarding — his first sewing experience. After a brief stint in fashion school, a series of colorful incarnations — he once made rhinestone-embellished women’s undergarments (“they sparkled”) — led him to Amish country, where he has farmed for 12 years. On 20 acres, he grows organic heirloom tomatoes, vine peppers, beets, carrots, strawberries, blueberries, and hay that he sells at the local produce auction. A family of ducks lives both on his pond and in a gutted vintage 1953 Vagabond Airstream he calls the Duck Hotel.

It wasn’t until 2007, when a neighboring farmer brought his threadbare overalls to Myers, asking if he might be able to reproduce them, that Myers says he tried on his first pair of bibs. He took them completely apart, first making a pair for himself, then refined the design and fit. Thus the Zace The Great Overall Company sprouted.

Myers began buying up bolts of vintage denim from the now-defunct Dan River Mills, as well as Cone Mills and other places around the world. Then, based on his own needs in the field, he designed clothing that would survive farming’s abuse. After the overalls came tried and tested Harvester Hats, work shirts, coveralls, jeans, shortalls for women, jackets, and his Original Button Bandana that he boasts can be worn 14 different ways.

At first, Myers handled all the cutting and much of the sewing and finishing on his own. But orders rolled in from around the world as word spread from farmer to farmer and then to miners, painters, artists, musicians, and surfers. Looking for help, he recruited three local Amish families, switching their old, spare barns into sewing facilities where he converted the electric sewing machines to run on a manual line shaft. His is the largest collection of “old black machines,” as he calls them, in the country.

The extra work provides much-needed income for the farmers during the sparse winter months, and Myers says it builds community, too: “Our clothing is all farmer made, farmer tested, farmer true.”

Today, Myers has 5,000 pieces in his inventory. His ‘farm fashionable’ clothing sells for $40 to $279, and still spreads by word-of-mouth via Instagram and Facebook. He makes smaller versions of the clothing for his young sons — Denim, named for the fabric, and Diesel, for the beloved blue Ford tractor — who work with him in the fields. Word of his farm-based business has traveled. In the coming months, more Amish families will fit their barns with the old black sewing machines, creating a small and very local manufacturing neighborhood.

Zachary Myers

At the end of a long day of farm work, Myers climbs into his pickup and winds through the rolling landscape, three large bolts of fabric in the back. He’s headed for the Brush Hollow Farm, which belongs to an Amish man named Andy Miller, where with the help of a generator he’ll cut pieces for Myers & Meyers — a line of vintage clothing cobbled from old workwear patterns launched in partnership with Evan Meyers of North Carolina.

Miller, a small man who looks like musician Paul Simon save for a paintbrush wisp of hair marking his chin, steps into the workroom and shows a visitor how his own clothing is made. It’s built by hand, of course, and the sturdiness can’t be denied. “They know clothing,” Myers says of the Amish.

A goat bleats from the barn. Outside, Andy climbs into a black buggy pulled by a thick workhorse and rolls past a pickup laden with fabric that will soon be worn by farmers, miners, artists, and musicians across the globe. The wind picks up and Myers pulls the earflaps down on his denim Harvester Hat lined in blue chambray — a global favorite — and smiles. “It’s so rad, this here hat.”