Earlier this month, I moved cross-country using Amtrak. This is part three of the story. Part one is here, and part two is here.

Things I have learned while waiting for trains to come: If you’re someone who is interested in how working buildings adapt over time, train stations provide examples of just about every bad thing that can happen. The most dramatic has to be New York’s Penn Station, which is so difficult to navigate that I’m convinced the whole subterranean complex must be haunted by the vengeful ghost of the gilded cupcake of a station that used to be there.

In more remote areas, where train travel has dropped to almost nil, it’s common to pass an ornate boarded-up train station. Sometimes it will sit next to a cinder block hut that serves as the working station; sometimes there is no station at all. In the wake of de-institutionalization and the erosion of low-income housing programs, train stations, like a lot of other public spaces, became de facto homeless shelters, and more than a few cities decided that it would be simpler to close the stations than to fix homelessness.

Chicago’s Union Station is somewhere in between those two options. The great hall — which was cinematically immortalized in such scenes as the “baby carriage bouncing down the steps that was totally ripped off from the Battleship Potemkin” in the gangster film The Untouchables — is still there, but traffic doesn’t flow through it anymore. In the late ’60s the Beaux Arts concourse that connected the Great Hall to the train tracks was demolished in order to make room for a skyscraper. The real work of the station was moved into a warren of tunnels underground, which were decorated, in keeping with the fashion of the time, in the generic, linoleumed, low-ceilinged style familiar to anyone who has spent a lot of time in hospital waiting rooms.

By cutting away everything that was useful about the building and only leaving what was most beautiful, the Great Hall became an amputated limb that the city of Chicago had chosen to hang onto for sentimental reasons. The first time I passed through the station, in the late ’90s, it took me a while to even find the hall. When I did find it, it was dim, cold, and empty, except for a colony of homeless people who glared at me balefully as I walked as quietly as I could around the perimeter of the hall, taking in the architecture. But my footsteps echoed through the space like someone dropping bricks onto a tile floor.

The next time I saw it, in 2012, it was — like so many big old spaces that no one quite knows what to do with — being rented out as an event space. The benches were gone and instead there was a pop-up shop selling luxury menswear. Today, the benches were back — and they had people sitting in them, with carts of luggage and children chasing each other across the floor like flocks of sparrows. The great hall was still far away from where the trains actually came and went, but passengers were using it now.

Union Station was also busier than I had ever seen it before. In the 2008 recession, Chicago, like a lot of American cities, saw the number of people using its public transit system skyrocket, to the point where it expanded platforms outside of several elevated train stops so that they could fit more passengers. The same thing was also happening at Union Station. Train traffic has already expanded past the small ’70s-era underground concourse, and it’s expected to increase by 40 percent between 2011 and 2040.

Dealing with this after having sold so much space to a skyscraper developer is a little awkward — especially since routing passenger trains underground is a tricky business if you like breathing. The station is trying to figure out how to fit more train platforms into the space that it had left and working on converting train platforms that were being used to ship mail for passenger use.

I would linger, but I’ve got to get going. The six-hour layover in Chicago between the second leg of a cross-country journey — which I have historically used as an excuse to explore, replenish my train food supply, and eat lots of pizza — isn’t happening, because my train got routed behind so much freight on the way here. I’ve got less than an hour, which means that I have to go downstairs and get ready to board.

There is an unmistakable shift in train culture as soon as we board the California Zephyr. And the Zephyr is a sightseeing train — it’s on one of the most stunning train routes in North America, and so there’s plenty of passengers on holiday, instead of just people trying to get from one place to the next. As I walk to my seat, I see a college-age woman reading On the Road. Why not? It’s definitely easier to read a quintessential car travel memoir on a train than it is while driving a literal car.

I, unfortunately, am not on holiday. I brought a wireless hotspot with me, because I had this picturesque vision of myself taking the train and gaily posting things to the internet as the train wound its way up through the Sierras, but forgot the part about America being a large and sparsely internetted place, and definitely not the kind of place where you can upload a large photo to a remote server from just anywhere. I struggle with an internet connection that flickers in and out as, around me, adorable senior citizens flirt and card shark each other.

I try to be calm about this. Surely, I can manage to navigate this sporadic connectivity — downloading research and posting while the train passes through urban areas, and just writing when we’re going through the wilderness of no connection. But this proves tricky. Cities appear and disappear in a matter of minutes. I start to want to be an adorable senior citizen. I want to play cards, and read mysteries, and drink tiny bottles of wine purchased from the café car.

When night falls, I realize that I forgot about one critical characteristic of the California Zephyr — at night, it’s so cold you feel like you’re trying to fall asleep in a walk-in freezer. The pros have brought pillows and blankets and even full sleeping bags with them. I finally manage to get to sleep after putting on a stocking cap, scarf, and all of the sweaters in my luggage.

Every few hours, there’s a stop along the route where passengers are allowed to get out and walk around. I have been cautious about doing this, both because you have to be careful not to get between a smoker and the door — they will trample you — and because I’m addicted to the strong wifi connection that I get when the train is sitting at the station.

But after two nights of sleeping on the train, I’m getting progressively more and more stiff. And I’m getting hungry. I’ve eaten all the food I packed and I didn’t have a chance to buy more food in Chicago. When the loudspeaker announces that the train is going to be stopping for 20 minutes I pack up my laptop and get in line outside the door.

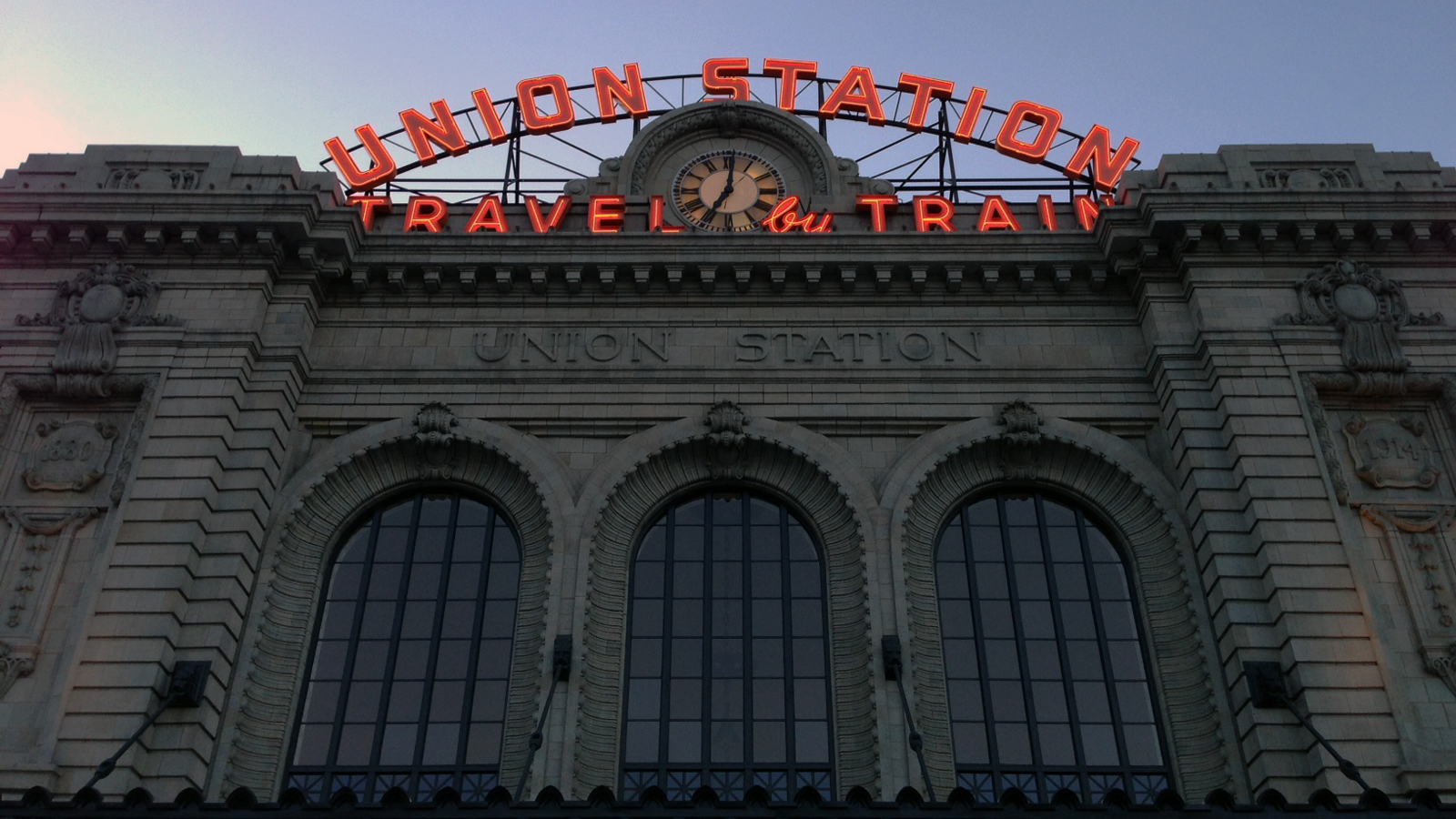

When I step onto the platform, I get a distinct feeling that something is up with Denver. I passed through the city once, and it was not fun. It felt like a suburb without end. There was endless driving, and missing of freeway exits. It would not have even occurred to me that Denver had a downtown, but stepping out into the platform, it is clear that Denver is busy creating one, or rebuilding it.

The concrete on the train platform is freshly poured and still a light, porcelain gray. The train station is a huge white cupcake of a building that has been renovated into what could have plausibly have been the interior of the station when it opened in the 1890s, but probably wasn’t. The upper floors have been turned into a hotel. There’s an ornate bar with dark paneling, shuffleboard tables, a bookstore, a fancy ice cream shop, a breakfast place that is packed with people, and a coffee shop that also looks very nice but, as it turns out, serves not very good coffee. I don’t even care. I’m so amazed that any American city has put this much time and money and thought into a train station. And it is brand new — the shops at the newly renovated station only opened a month ago.

In all the years I’ve spent waiting for Amtrak, I’ve waited for trains in stations that felt designed to maximize human discomfort: South Station in Boston, with its endlessly looping Homeland Security announcements and its metal chairs that screech bloody murder if anyone so much as wiggles in them; Penn Station, with its interminable hallways and the smell of fried food cooked deep underground; the station nearest to my parents’ house, which isn’t even a station — more like a low wall next to a parking lot. I have never had access to anything so glamorous as a bar, and I wish it was open, so that I could order a thousand cocktails and drown out all those times I have shivered in a basement with only a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise to keep me alive.

When I walk back out to the platform, I notice that the train station is surrounded by cranes and half-finished tower buildings. It’s part of a larger transportation and development project — high-density housing downtown, and a light rail system stretching out from it to the burbs that is one of the most ambitious of its type.

I have to take a strange pathway to get back onto the train — the only door is one that has been left open in the back of one of the sleeping cars. As I walk to my seat, the train lurches forward and I realize that I almost got left behind. “What just happened?” I say to the train attendant. “I thought you were going to blow the whistle before you left.” She shrugs. “You can’t hear it from inside the building,” she says.

So there’s that. I almost got left behind to start a new life in Denver. As it is, I’m all out of snacks. It’s time to break down and finally go to the dining car.

Read on to the final part of this story.