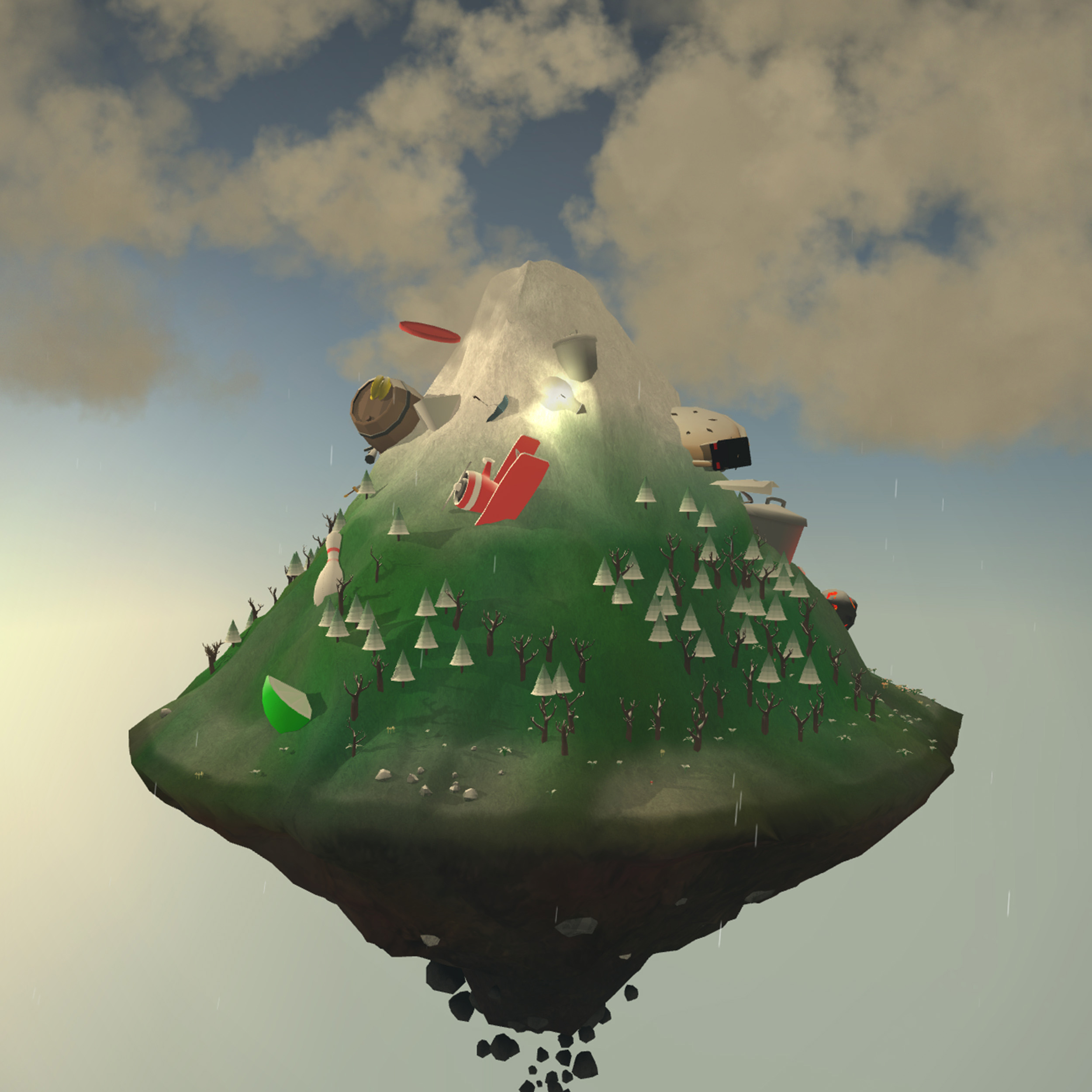

It only took a few hours of playing the new video game Mountain for a thick layer of smog to shroud the top of my virtual peak. Soon bits of detritus, like a satellite dish and an airplane fuselage, started piling up on its flanks. I’d barely played and already things were not looking good for the environmental future of Mt. Me.

But maybe ‘playing’ isn’t quite the right word: Once the game is running it feels a bit like you’re a landlord with an unruly tenant. Mountain is a new video game from David OReilly, the animation director for Spike Jonze’s Her. (He designed the in-movie game that featured a memorably vulgar alien baby squaring off against Joaquin Phoenix’s character.) The game asks you some esoteric big-picture questions, like what your idea of hope or fear looks like, and then it builds you a mountain — an ecosystem floating on your screen. It lives on your computer or phone, pinging you every once in a while to keep you updated on its status. After you’ve started, you can’t change the impacts you’ve set in motion. You cede all control and the world develops on its own: Storms swirl around the peak, seasons come and go, and your mountain gives you feedback about how it’s doing. “I feel dissolved inside,” mine said, as trees wilted in a haze.

Here’s a trailer for the game:

It’s not the first video game to show how people impact the planet. They’ve been around since at least the late 80s, when Populous was released for the Amiga and Atari. But now developers are putting an intentional environmental spin on games. OReilly is cagey about the intent of the game: “I have my own interpretation of Mountain which I don’t talk about,” he says via email. He encourages users to interpret the ecological impacts however they want. But as counterintuitive as it might seem, games like “Mountain” can actually be an effective tool for talking about climate change.

A recent study from UC-Irvine anthropologist Bonnie Nardi and Oregon State communications professor Shawna Kelly discovered that video games can explain complex concepts about climate change in a non-preachy way, and — because gaming is inherently solution based — even offer pathways to address it. The study says that, “Many popular video games sustain compelling storylines that narrativize scarce resources, promote competitive and collaborative social interaction, and foreground survival goals — all necessary skills for making sense of a changed and changing global environment.”

If perhaps it seems off-putting to use a screen to explain environmental issues (go outside, kids!), Kelly notes that it can destigmatize the sanctimony some people associate with greenness and reach people who might otherwise be turned off by talking about climate change. Game-based learning is an effective teaching tool, and game theory, at its heart, is the process of solving complex problems. Put a subtle “let’s not eff up the planet” spin on it, and maybe you can find a way to reduce atmospheric carbon — or start the next generation thinking about how to do it. (Or at least maybe they’ll be inspired to design bike lanes.)

“Using video games, it’s possible to introduce sustainability concepts to the mass public in a way that’s not pedantic, that’s not educational,” Kelly said. “Instead, it could be fun and it could be challenging.”

Games mirror life in that cause and effect are directly correlated. But games remove the noise to put the cause-and-effect of tangled, complex issues into stark relief. Some of that has to do with speed: Mountain, for instance, runs for about 50 hours before your mountain dies. That means players can understand eons of climate impacts on a none-too-impervious facet of the Earth’s geography in compressed, relatable fashion. In that respect, “Mountain” carries on a proud tradition started by a landmark game: Anyone who played “SimCity” as a kid knows what happens if you cut your city off from water or energy. There are probably more than a few urban planning careers that started behind a laptop, and the makers of the game seem to know this. Last fall, “SimCity” launched “SimCityEDU: Pollution Challenge!,” specifically for use in middle schools, because it could show how people were directly impacted by resources or lack thereof.

The real world obviously isn’t as linear as a game — and the true complexity of climate change can’t be conveyed in even several hours of play. But games can provide a framework for understanding the fair distribution of scarce resources and illustrate how human activities influence climate change on a scale that’s easy to visualize and understand.

Game developers aren’t the only ones trying to take advantage. In 2012, Al Gore’s Climate Reality Project started a “Gaming for Good” project, where they asked designers to build video games that explained sustainability and climate issues. The project led to Climate Trail, an energy-related spin off of Oregon Trail complete with 80s-style graphics.

Getting people to understand human-induced climate change is one thing, but getting them to do something about it is another — but game theory has solved complex problems before. University of Washington AIDS researchers spent 10 years attempting to map the structure of an enzyme that could be a big part of a potential HIV treatment drug before presenting it online as a game called Foldit in 2011. Gamers helped solve it in 10 days.

Kelly’s study identified a few main areas where games could engage people in sustainability. Because games have set parameters, they can teach people what it means to succeed within limits. Moving away from unmitigated growth as a societal and governmental goal, leveraging social interaction, strategizing resource use, interacting with the environment in creative ways — these are all ways to win in games and in the climate fight.

The challenge is creating a sense of consequence when you have a restart button. That’s where games like OReilly’s are an interesting model: You have to live with the cost of what you create. In “Mountain,” there are no take-backs — and you aren’t in control of everything. You can’t change the game until it’s over. At one point, desperation seemed to be getting the better of my mountain. “I am alone in this dark night,” it said. But despite the virtual ennui, by the end I wanted to try again and do better.