Officially, the first day of spring is whatever Google says it is when one searches “first day of spring.” Scientifically (at least in the U.S.), it’s the day when the center of the sun passes over the equator. And to meteorologists, it’s always March 1 — but that makes everything confusing, so get out of here, meteorologists!

Regardless of the calendar date, the start of spring is that magical time of year when flowers bloom and the sun shines and birds chirp and blah blah blah — except it’s not due to magic at all. Leaves come out and flowers bloom in spring because weather conditions are right. And if weather conditions are altered due to climate change, that means the start of spring could come earlier or later than we’re used to — which could cause problems for, say, the agriculture industry or wildlife management.

Enter “springcasting,” which predicts when spring will start in a given area based on local, real-time weather data. The concept is based on research from University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee geologist Mark D. Schwartz, who studies the correlation between weather conditions and the timing of “leaf-out” (which is exactly what it sounds like) and bloom in certain plants.

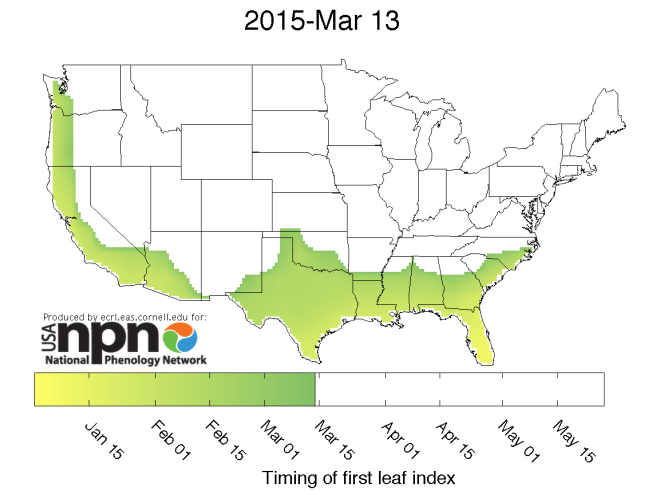

This year’s map shows that spring already starting in the South and on the West Coast (stay strong, Northeast!).

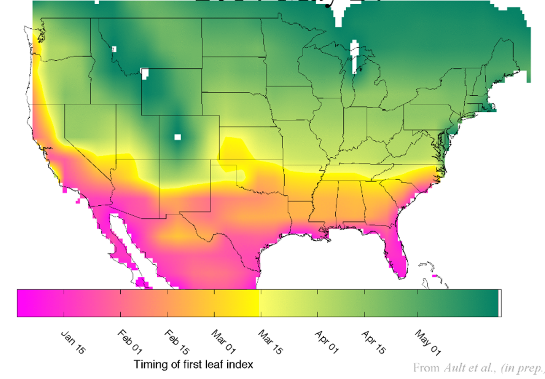

Here’s last year’s map:

Ault et. al

If so inclined, citizen scientists can get involved by reporting on the accuracy of the model. Were you told you’d have spring by now, but all you see outside your window is a barren wasteland? Say something! Your feedback could help the scientists improve the model.

Beyond practical applications like helping farmers figure out when to plant their crops, springcasting can also help scientists track climate change and understand its effects on vegetation. In an interview with the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee news service, Schwartz said that it’s also useful for communicating with the public about climate change:

When I talk to people about change, I can say, for example, that over the Northern hemisphere from the mid-1950s to the early 2000s, the timing of the beginning of spring using my models has gotten earlier by about a week. It’s a very easy thing to explain. It’s something that most people can readily understand.

In case you haven’t Googled it yet, the first day of spring this year is technically Friday. But remember, there’s nothing magical about blooming flowers, so don’t be too jealous of the already-blossoming West Coast (sorry!) if your forecast remains depressing as hell for a while.