By now, most people are aware that solar power — particularly distributed solar power, in the form of rooftop panels — poses a threat to power utilities. And utilities are fighting back, attempting to impose additional fees and restrictions on solar customers. These skirmishes generally center on “net metering,” whereby utilities (forced by state legislation) pay customers with solar panels full retail price for the power they produce, which can often cancel out the customer’s bill entirely. That’s lost revenue for the utility.

Net metering, however, is largely a distraction, a squabble over how long utilities can cling to their familiar business model. Larger reforms are inevitable, because the threat to utilities goes far beyond solar panels and demands a response far more substantial than rate-tweaking. Sooner or later, there must be a wholesale rethinking of the utility business model. And if utilities are smart, they’ll do it sooner.

To understand why, let’s have a look at two recent analyses. One examines the short-term issue for utilities, revealing the core problem lurking within. The second pulls the lens back to take in the big picture.

—–

First, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) has a new analysis examining “Financial Impacts of Net-Metered PV on Utilities and Ratepayers.” It’s interesting because it doesn’t take any position on the larger question of how much solar is “really” worth or how utilities ought to compensate it. Instead, it takes net metering for granted and simply examines its financial impact on the shareholders and ratepayers of two prototypical investor-owned utilities. One is a vertically integrated utility (owns power generation and distribution wires) in the Southwest and the other is a “wires only” (no generation) distribution utility in the Northeast.

LBNL analyzed what would happen if solar PV penetration rose to between 2.5 and 10 percent of total retail sales by 2022. For reference, the current national average penetration is 0.2 percent and even the most solar-friendly utilities (outside of Hawaii) have only gotten to about 2 percent. So 10 percent would be a huge deal.

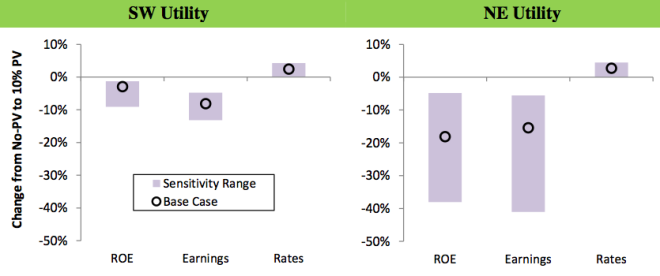

We don’t need to get into the weeds of the LBNL analysis. Let’s just skip to the conclusion. Here’s the key chart, showing what would happen if net-metered solar PV achieved 10 percent penetration by 2022 (ROE is return on equity):

In short, solar PV at 10 percent would reduce return on equity and earnings a lot — 40 percent in the case of the wires-only utility — but raise rates only a little. (Why the sharply different impact on the two utilities? Because the wires-only utility only invests in wires and other distribution infrastructure, and those are the kinds of investments that solar PV renders unnecessary.) I don’t know if this is a big enough hit to constitute a “death spiral,” but it certainly isn’t good news for utilities.

I’ve seen a few write-ups of this study — in particular the always excellent Ben Paulos — but none that sufficiently emphasize what I take to be the key lesson here: Solar PV is mostly a threat to utility investors and shareholders, not ratepayers. It is utility profit, not adequate provision of reasonable-cost power, that stands to lose from the rise of PV (and other distributed energy solutions).

—–

Utilities have suggested various remedies to this problem, usually fixed charges that have to be paid by all ratepayers and/or some way of remunerating the utility for reduced demand (which is what “decoupling” does with efficiency). Note, however, that these solutions share something in common: They treat distributed energy as a loss, for which utilities have the right to be compensated.

Why? Because, as I explained last year, a utility “makes money not primarily by selling electricity, but by making investments and receiving returns on them. If it builds more power plants and power lines, it makes more money.” All those investments are made on the basis of demand projections. If demand declines unexpectedly, if distributed energy helps consumers become more independent — generate some of their own electricity, store some of it, manage it more intelligently through sensors and automation — then utilities risk having those investments “stranded,” to the detriment of shareholders.

If you think about the situation a little, you will note that it is insane. Socially and environmentally, we want more distributed, clean power; we want more efficiency and lower demand; we want more grid resilience and intelligence; we want to avoid huge, expensive infrastructure investments if possible. But the way the utility business model is set up, all that stuff slashes utility profits. Our power utilities are structured to oppose our social and environmental goals. That is the real problem at the core of all these discussions. (For much, much more on this, see my series on utilities.)

For better or worse, this isn’t just a problem for climate hawks. Now that solar PV and other distributed energy solutions are growing, it’s a problem for utilities too. Standing still is not an option. They either adapt or face the much-discussed “death spiral.”

—–

That’s what the second analysis is about: “Does Disruptive Competition Mean a Death Spiral for Electric Utilities?” It’s in Energy Law Journal, by Elisabeth Graffy and Steven Kihm.

It begins with a simple premise: The growth of distributed solar PV is not an isolated or one-off phenomenon, but the leading edge of “a synergistic wave of innovations occurring in several sectors at once—technology research and development, policy development, social and cultural preferences, scientific investigation, and business.” After nearly a century spent in a zone of limited-to-no competition, utilities are entering a zone of disruptive competition, in which customers can reduce or even eliminate their dependence on utility power and grid services.

Graffy and Kihm describe two broad strategies utilities might choose to cope with this wave: value creation and cost recovery. The former is more promising, but requires more substantial adaptation of institutional practices. The latter might stave off changes for a little while, but by doing so it makes utilities more vulnerable when changes become too substantial to resist.

Needless to say, utilities are not prepared for this sh*t. At all. After a century of enjoying regulated-monopoly status, with returns guaranteed by law and expansion as far as the eye could see, utilities have virtually none of the organizational foresight and habits needed to respond proactively to disruptive threats. So at least at the beginning, they’re going for cost recovery.

That’s what the fight over net metering is all about. When customers shift to distributed solar, they pay the utility less than the utility had forecast; that means the utility has made investments in infrastructure that now risk being stranded. So they want to impose new fees to recover those costs.

It is the standard utility play and one they’re quite accustomed to. They’ve been protected from competition by regulators for decades. But in present circumstances, the strategy poses three dangers:

First, it requires successive upward recalibration of customer rates as system costs remain largely fixed while electricity use shifts from the grid to distributed systems. Second, it encourages utilities to defer corporate adaptation unless a deep crisis forces the issue. Third, it encourages them to take actions that slow innovation either by competitors or in the policy domain. Customer backlash, loss of regulatory support, high opportunity costs, and institutional brittleness to external shocks are all foreseeable byproducts that put utilities at greater risk.

“Customer backlash” is a key piece here. If utilities penalize those attempting to increase their own energy independence through “behind the meter” power generation, storage, and management, the result will be angry customers. (It even pisses Tea Partiers off, thus the Green Tea Coalition.) When you’ve got a bunch of dissatisfied customers seeking non-grid alternatives, you’ve got a growing market that will attract more and more entrepreneurial attention, thus accelerating customer defections.

The longer utilities try to hold back the wave with legal or regulatory roadblocks, the harder it will hit them when it finally comes. Recent history provides an analogue:

[T]he music industry viewed the peer-to-peer song-sharing software, Napster, as a conventional threat rather than as the leading edge of a wave of disruptive competition that challenged the fundamental business model for distributing music. By doing so, the industry became more vulnerable to the market transformation subsequently generated by iTunes.

—–

As accustomed as they are to turning to regulators for help, utilities might soon run out of luck. It is their social mission that justified their business model; if the social mission is no longer being served, well:

Herein lies the vulnerability of regulated utilities. The model is designed to maintain institutional stability in order to uphold social welfare objectives (in the historical case of energy, for example, to ensure low cost, reliable service), not to uphold the welfare of utilities themselves. Historical precedent clearly shows that when emerging conditions create a critical tension between upholding social welfare objectives and upholding continuity of a utility for its own sake, courts will decisively favor social welfare objectives and markets play no favorites. Indeed, neither regulators nor courts can ultimately protect regulated utilities from all competition, even when—perhaps especially when—the character of that competition challenges the viability of their fundamental business model. [my emphasis]

Graffy and Kihm cite two contrasting historical examples to help make this point.

The first is Market Street Railway, a streetcar utility in San Francisco. From the 1900s through the 1920s, it was an expanding, innovating enterprise. But streetcar ridership peaked in 1920, as riders began defecting to alternatives (buses and cars). By the 1930s and ’40s, the utility had entered a period of disruptive competition. It tried to defend itself through cost recovery, asking the Railroad Commission of California to raise its fares from five cents to seven cents. As you can probably guess, the higher fares did not increase utility revenues or profits. It just drove more people to alternatives. Seeing that, the Commission bumped it back down to six cents. The utility sued and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled decisively that even regulated monopolies have no constitutional right to protection from competitors. Meanwhile, Market Street Railway went bankrupt and all those streetcars became “stranded assets.” This is the “death spiral” utilities fear.

In contrast, consider the cable TV monopolies of yore. Their crap service drove customer demand for alternatives, and lo, DirecTV rose to answer the call; now the internet is driving even more competition. Cable companies suffered; some, like Charter, declared bankruptcy. But Comcast, rather than trying to recover costs by raising rates, focused on value creation, bundling services like cable, phone, and internet together in new ways to meet customers’ evolving demands. It innovated in advance of disruption. Now internet service is its most valuable product and it basically rules the world, despite, if we’re honest, still offering crap service.

Which way will electric utilities go? They can look to regulators to impose new fees, to help them recover costs, but that will just drive more research and innovation into alternatives, pushing more consumers away from the grid. That way lies the death spiral. If reliable, reasonable-cost power can be provisioned without profitable utilities, well then, so much the worse for utilities. Graffy and Kihm discuss a series of recent legal and regulatory decisions — in Iowa, Wisconsin, Arizona, and elsewhere — indicating that regulators and courts are not particularly inclined to defend utilities from clean energy.

So what should utilities do? Graffy and Kihm suggest a pivot to value creation. Instead of viewing ratepayers as passive sources of cost recovery, utilities ought to view them as, y’know, customers. Offer them products and services that satisfy their evolving preferences. That might mean following Comcast’s lead and offering unique bundles like solar panels with energy storage and management.

Traditional utility service prices electrons as commodities, and commodity markets compete on a lowest cost basis. Energy-related bundles are not commodities but rather value-added products and services, and the acceptable cost bases to customers may be very different. They are not, after all, only buying electrons. They are buying convenience, security, peace of mind, and the ability to engage in energy arrangements that fit their values of sustainability or energy independence but which they cannot do alone.

… The bundled product-service package is likely to meet a broader and somewhat different set of customer needs than legacy electron provision.

As they note (in rather too cursory a way, in my opinion), allowing utilities to play in these kinds of markets would also require imagination and flexibility from public utility commissions, which, like utilities themselves, are not exactly hotbeds of forward-thinking next-gen synergistic entrepreneurialism.

The utility sector is still an old boy’s network, especially in some parts of the country, so one rather despairs in turning to utilities for innovation. But nothing focuses the mind like the threat of bankruptcy.

Graffy and Kihm conclude:

Protecting the utilities from the effects of competition is not the public policy goal behind regulation. Legal precedent affirms that while protecting utilities in the interest of reliable and consistent service can be robust, it can only go so far. The prospect of a semi-regulated, differently regulated, or even unregulated electric provision sector is not outside the realm of possibility as current trends continue. How utilities are ultimately repositioned depends, to some degree, on their capacity to demonstrate leadership that aligns with redefined needs, preferences, and constraints facing all electricity providers and users. … [G]ambling on maintenance of the status quo seems like a losing hand.

Indeed.

—

Further reading:

Utilities getting into selling energy products and services is a good idea, as far as it goes. But utilities can think much bigger than that. Last year I wrote a long post about what utilities for the 21st century might look like. Once your eyeballs have stopped bleeding from reading this post, check that one out.

The Rocky Mountain Institute’s eLab has a blog post called “Why the Net Energy Metering Debate Misses the Point,” which stresses the importance of rate design and links to its longer report, “Rate Design for the Distribution Edge.” They’re worth reading as a kind of intermediate solution between the blue-sky dreaming I do in the post mentioned above and the small-beans rate-tweaking utilities are talking about today.

My colleague Brentin Mock has been writing about the scummy campaign by dirty energy to convince minority lawmakers that net metering is a threat. It’s a crucial issue — follow him.