First off, a warning: This is probably going to be hard to watch. But if you eat meat — even the humanely raised, locally butchered, lullabied-to-sleep-at-night kind — you probably should watch it anyway.

Out in the far North Atlantic, in the tiny Faroe Islands, an isolated population of 50,000 subsists largely on what it can eke from the steep, uncharitable land (mostly sheep) as well as what they can haul from the sea. And for hundreds of years, that has included pilot whales — to the horror of marine conservation group Sea Shepherd, who recently sicced hundreds of volunteers and a half-million-strong social media following on the people of the Faroes, in an attempt to put an end to this practice once and for all.

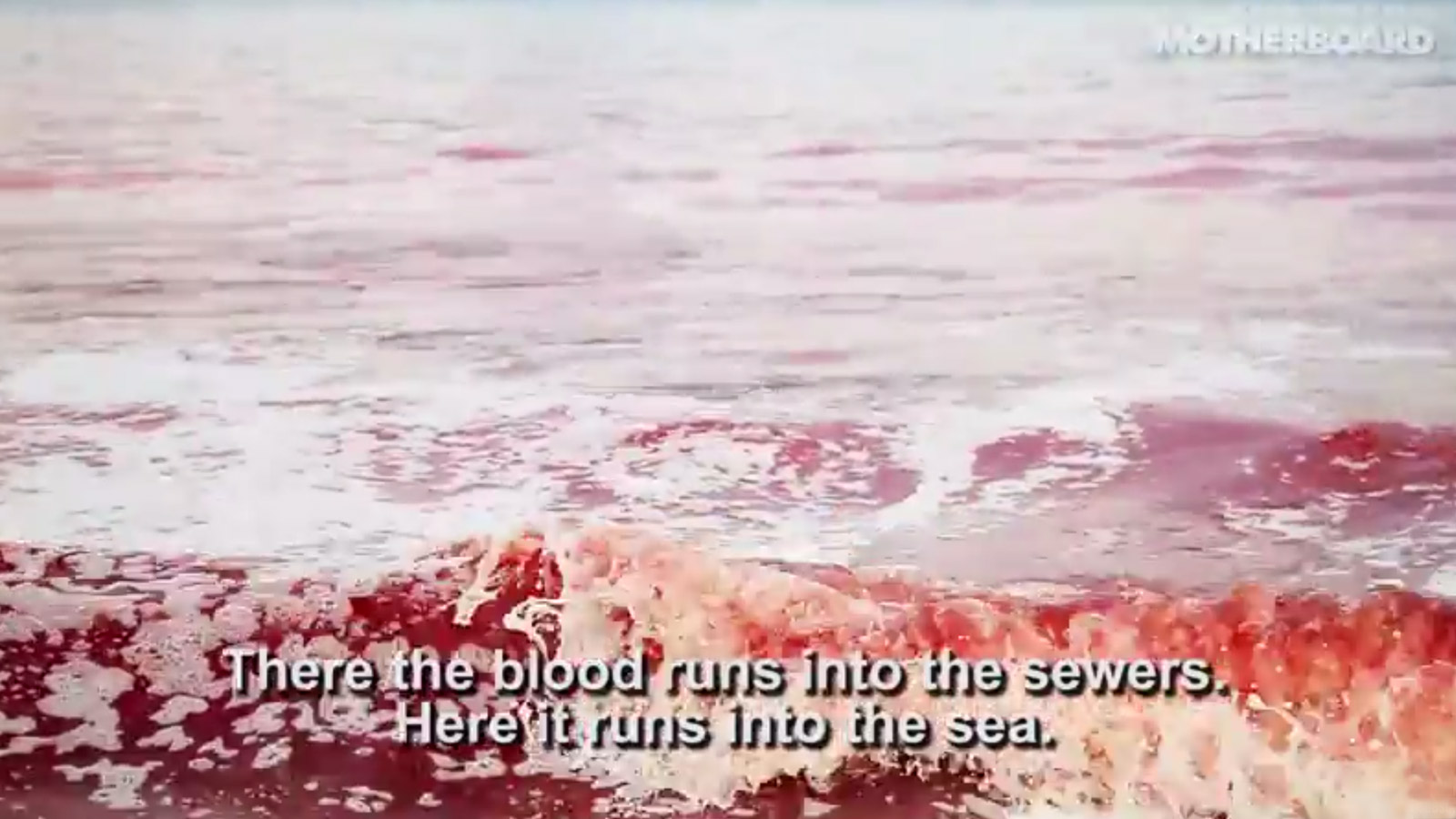

Every year, the Faroese hunt and butcher an average of 838 whales. The grind (pronounced grinned), as the whale-slaughter is called, is not a commercial harvest — the meat is divvied up amongst the community, and largely eaten for special occasions. It is, however, pretty gruesome if you’re not used to slaughter: Faroese fishermen drive a pod of whales onto one of a handful of approved landing beaches, where a crowd waits to sever their spinal cords and cut their throats. There is so much blood that the water turns red. The bodies are dragged onto shore, where they are cleaned and butchered by the families who will share the harvest.

It’s gnarly, but that’s the thing about eating meat: There will always be blood. Regardless of whether you’re buying shrink-wrapped boneless chicken breasts at the grocery store or slaughtering a pig you raised, death is always part of the deal.

Motherboard producers Elise Coker and Ed Ou went to the Faroe Islands last summer to document the grind, and the controversy surrounding it. In the opening lines of the documentary, a Faroese man explains why the whale hunt is an especially easy target for public outrage: “We have an outdoor slaughterhouse. In other countries, the slaughterhouses are indoors. There the blood runs into the sewers. Here it runs into the sea.”

As Coker pointed out to Grist, this is about more than just whales: “The Faroese are very in touch with where their food comes from. Violence is not an abstract concept to them — it’s very much a part of their life.”

And so we watch a fisherman net a seabird and twist its head off, and a family stun and bleed a sheep. This may showcase the darker side of eating animals, but it’s a portrait of how a very local food system functions — and it’s arguably about as sustainable as eating can get in such a remote place.

But that lifestyle is under threat from more than just concerned animal-rights activists. Pilot whale meat contains so much mercury from decades of industrial pollution that it is no longer safe to eat in any significant quantity. Meanwhile, pollution, fishing, and ship strikes kill hundreds of thousands of whales a year, and rarely make the news. The Faroese, for whom a literal whale bloodbath is almost mundane, know that it’s the intimacy of the violence in the grind that shocks outsiders — but, they suggest, it’s our distance from the violence underpinning the rest of our lives that’s truly dangerous.