That message in a bottle you tossed into the sea as a young rapscallion? Remember how you didn’t get a response? It’s because oceans aren’t the same thing as carrier pigeons. Instead of sending bottles bobbing merrily on their way across the Pacific, ocean currents tend to push bits of trash to convergence points in the ocean called garbage patches.

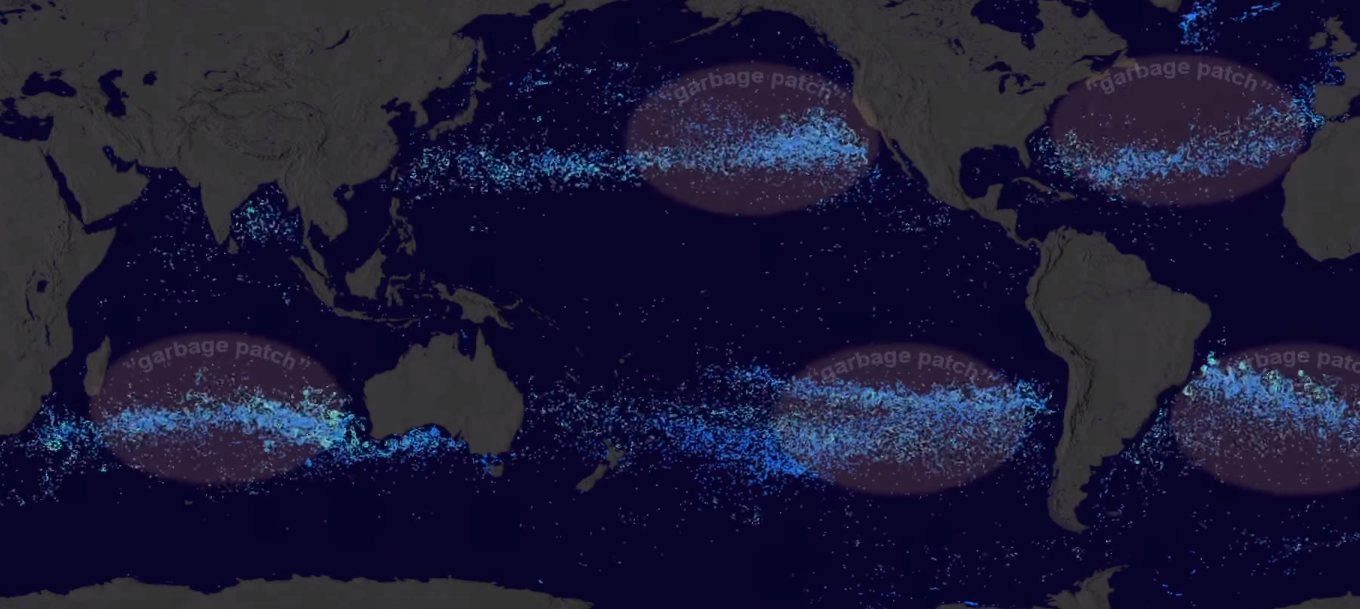

The video above shows a new data visualization from NASA illustrating the phenomenon. By mapping the paths of free-floating ocean buoys distributed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration over a period of 35 years, scientists were able to verify the garbage patch effect, as well as the locations of the patches. Aside from providing these insights, the visualization is a win for science, because the researchers were able to lend some more validation to an ocean current model called ECCO2. When the group generated a cloud of particles — digital buoys — and ran the model, the particles ended up in the same spots as the physical buoys they’d been tracking.

There are probably more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the ocean. The message in a bottle example might be a bit of red herring, though, since most of the plastic floating in the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” is thought to come in the form of microplastics smaller than a thumbtack, which are distributed throughout the water column at the rate of about one piece every two cubic meters of water. That said, a recent expedition gathering data on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch trawled up mostly medium to large-sized pieces of trash. Either way, there’s a lot of garbage out there. You’re better off sending a postcard.