Shutterstock / Oleinik Dmitri

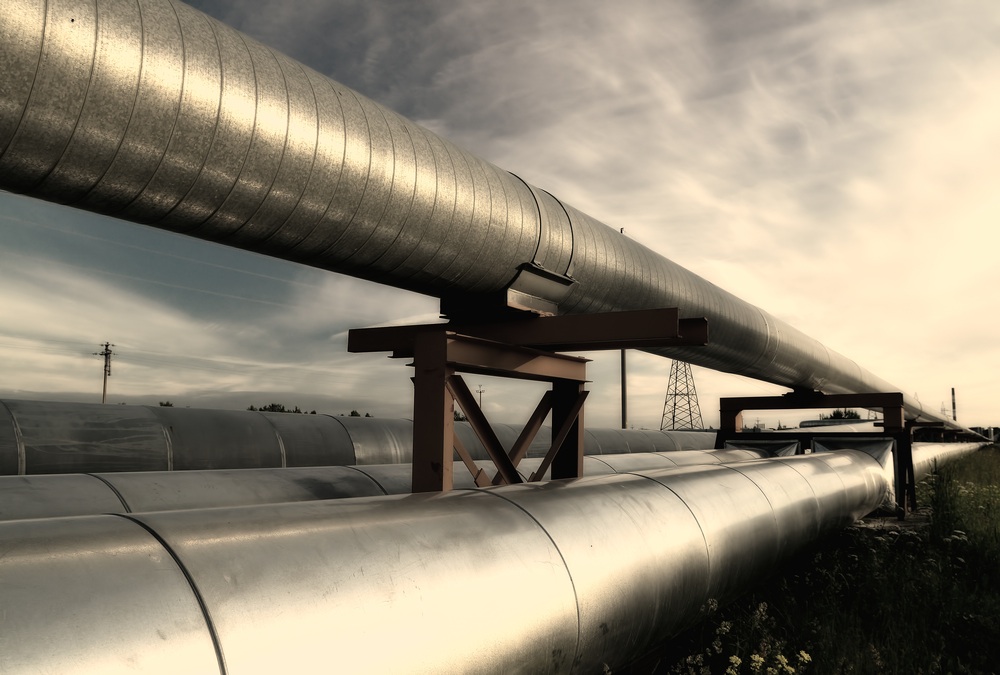

ExxonMobil’s oil spill in Mayflower, Ark., was just the latest in a string of leaks from pipelines that proved physically incapable of safely carrying toxic tar-sands oil.

With the Obama administration poised to decide whether to build the Keystone XL pipeline to carry Canadian tar-sands oil south to the Gulf Coast, you might well wonder whether that pipeline would be about as safe as a balloon filled with bleach.

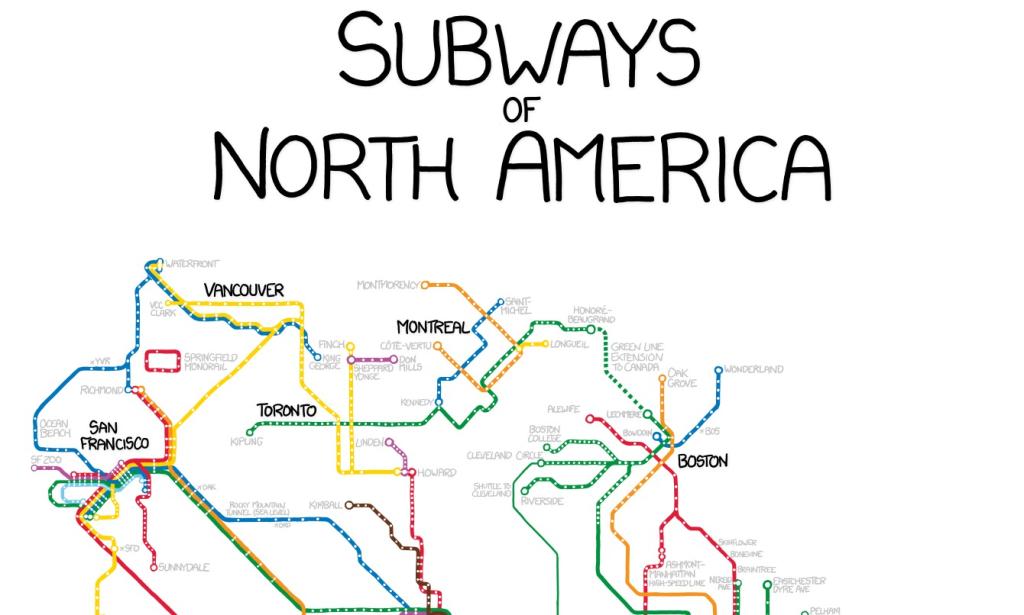

Tar-sands oil extraction and transportation is a relatively recent development, but the material already seems to be bursting out of pipelines and into the environment at a frighteningly disproportionate rate. From a Natural Resources Defense Council analysis of federal transportation data:

Diluted bitumen has only been moved on the U.S. pipeline system since the late 90s and federal regulators still don’t provide data with the specificity to evaluate the safety record of pipelines moving tar sands. But a close look at pipeline incident data from states in the northern Midwest, which have seen the greatest volumes of tar sands diluted bitumen over the longest time period, is alarming. Pipelines in North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan spilled 3.6 times as much crude per mile than the national average between 2010 and 2012.

NRDC attorney Anthony Swift and his colleagues have been making a lot of noise about the fact that pipelines are especially prone to spills when tar-sands oil is piped through them. Scientific American recently took a sobering look at those claims:

Critics charge that pipelines carrying diluted bitumen, or “dilbit” — a heavy oil extracted from tar sands mined in northern Alberta — pose a special risk because, compared with more conventional crude, they must operate at higher temperatures, which have been linked to increased corrosion. These pipelines also have to flow at higher pressures that may contribute to rupture as well. …

The chemistry of the tar sands oil could contribute to corrosion as well. In processing, the tar sands are boiled to separate the bitumen from the surrounding sand and water, and then mixed with diluent — light hydrocarbons produced along with natural gas — to make the oil less viscous and able to flow. But even so, the resulting dilbit is among the lowest in hydrogen as well as the most viscous, sulfurous and acidic form of oil produced today.

Some think the Arkansas spill could have resulted from [a] combination of aged infrastructure and added stress from dilbit, although an exact cause has yet to be determined. The breached Pegasus Pipeline involved in the Arkansas incident can carry nearly 100,000 barrels of oil per day from Illinois to Texas. Originally constructed in the 1940s to bring Texas crude oil up to Illinois, it had been reversed in recent years to stream dilbit. The operator, ExxonMobil, retrofitted the 50-centimeter tube to compensate for the demands of pushing tar sand oil through in the opposite direction, but the higher temperatures and pressures may nonetheless have contributed to the rupture or sped up preexisting corrosion, suggest critics such as NRDC’s Anthony Swift.

Not surprisingly, the government of Alberta disagrees with NRDC on this one. (Let’s not forget that the province is currently lobbying American lawmakers to approve Keystone XL.) Again from SciAm:

A study from the Alberta government [PDF], however, casts doubt on the notion that dilbit is worse for pipelines than any other oil is. It found that dilbit is not corrosive at pipeline temperatures of as much as 65 degrees Celsius, although it is highly corrosive at refinery temperatures above 100 degrees C. Nor is the fine sand that remains in some of the dilbit eroding pipelines, though it does form sludges that must be cleaned. The higher temperature operation may even kill off the bacteria that help to corrode pipelines carrying other types of oil. “There is no evidence that dilbit causes more failure than conventional oil,” geologist John Zhou of the provincial government research firm Alberta Innovates said during an interview in November on a trip to the tar sands; Zhou helped prepare the Canadian province’s analysis of dilbit. The U.S. National Academies is currently studying the issue.

As President Obama considers Keystone XL, which analyses will he be paying attention to? Perhaps he ought to ask the residents of Mayflower what they think.