Lithium-ion batteries are expected to play a critical role in the green energy transition, but despite surging global demand for the metals that go into them, we’re doing a terrible job recovering those metals after batteries die. A first-of-its-kind bill introduced in the Senate this month seeks to change that by significantly boosting federal investments in lithium-ion battery recycling.

Sponsored by Senator Angus King, an independent from Maine, the “Battery and Critical Mineral Recycling Act of 2020” calls on Congress to dole out $150 million over the next five years to support research on “innovative” battery recycling approaches and to help establish of a national collection system that can harvest the spent batteries gathering dust in our closets. Lithium-ion batteries power everything from smartphones to laptops to electric cars, but with the global appetite for clean energy growing rapidly, experts worry the world could soon face shortages of key battery metals.

The bill is the latest sign that politicians are becoming aware of this reality. It’s also a reminder that unless we figure out how to efficiently mine metals like cobalt and lithium from dead batteries, we’re going to need to mine the earth a lot more. And if we don’t figure out how to recycle lithium-ion batteries — particularly the big ones inside electric vehicles and those used for energy storage in the electric grid — we’ll eventually wind up with mountains of toxic e-waste.

Today, researchers estimate that less than 5 percent of lithium batteries are recycled at the end of their lives. Would-be recyclers face a host of challenges, including collecting enough batteries to make it worthwhile and finding safe, efficient ways to disassemble batteries that come in myriad shapes and sizes (and that often weren’t designed with recycling in mind).

Even if enough dead lithium-ion batteries can be collected to make recycling economical, today’s recycling techniques are rather crude. Recyclers might melt a battery’s metal-rich components down to slag in a furnace, dissolve them in acid to leach specific metals out, or use some combination of the two methods. Currently recycling processes are energy-intensive, produce toxic byproducts, and only recover some of the metals present, like cobalt and nickel. Most of today’s battery recyclers aren’t recovering lithium at all.

Better methods are in the works. In early 2019, the Department of Energy launched a $5.5 million Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling Prize and invested $15 million into a new lithium-ion battery recycling center, ReCell, housed at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois. Through these prizes and programs, researchers across government, academia, and the private sector are now working on a host of projects aimed at improving lithium-ion battery recycling. These include developing automated battery sorting methods, designing batteries for disassembly, and inventing new processes for recovering all of the metals inside the cathode, a battery’s positive electrode. The ReCell center is also focusing on “direct recycling” methods that rehabilitate cathodes so they can be put right to use in new batteries, no acid or furnaces required.

The new bill, if passed, would represent a major infusion of funds into these efforts, which could bring better recycling methods to market faster. In addition to re-authorizing the Lithium-ion Battery Recycling Prize, the bill directs the energy secretary to establish new grant programs for projects focused on improving recycling processes, designing batteries with disassembly in mind, integrating recycled minerals into new batteries, and boosting consumer participation in battery recycling. A separate grant would award state and local governments funds to establish battery recycling programs, while a third pot of money would go toward establishing a network of retail collection points to take back used batteries at no cost to consumers. Finally, the bill directs the EPA to develop a set of best practices for battery collection and calls for a voluntary labeling program, modeled after the Energy Star energy efficiency program, to promote battery recycling.

Payal Sampat, mining program director at the environmental nonprofit Earthworks, said that the bill represents an important step toward reducing the need for more mining to fuel the green energy transition.

“Cobalt, lithium, and nickel recovery, recycling, and efficiency must be scaled up rapidly, and we are encouraged to see legislation introduced to move us in this direction,” Sampat told Grist. “We hope this is only the first of many, and that future legislation is even more ambitious in terms of shifting the needle from mining to recirculating minerals.”

Gavin Harper, a research fellow working on lithium-ion battery recycling at the UK’s Faraday Institution, agreed that recirculation is critical. “The world is in the midst of a global commodities ‘arms race’ to secure access to critical materials,” said Harper. “Recycling the materials that are already in country, to form a secondary source of supply makes a great deal of sense.”

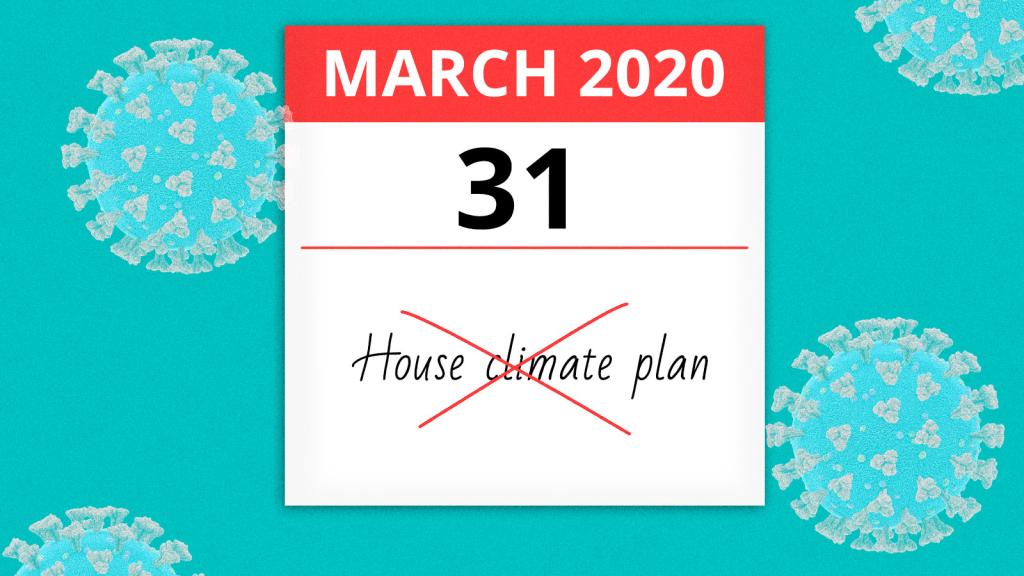

Whether or not this common-sense proposal comes to pass is another matter. King pushed for the bill to be included in a bipartisan energy package, the American Energy Innovation Act, championed by Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. That bill appears to be dead on arrival after a dispute over hydrofluorocarbons, greenhouse gases used in air conditioners and refrigerators. Senator King’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment on whether he expects any resistance to the bill. R&D spending at the DOE often enjoys bipartisan support during normal times, but such spending is unlikely to be a priority as Congress weighs its response to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic fallout.

Even if the bill becomes law, it’s only a first step. It doesn’t establish any new regulations that would compel companies or municipalities to beef up their battery recycling efforts. It also doesn’t place as much emphasis on battery reuse, which, in a time of growing metal scarcity, may wind up being as important as recycling. A battery that’s no longer fit to power a car, for instance, might still hold upwards of 70 percent of its initial charge capacity, making it useful for grid energy storage — something that entrepreneurs are beginning to recognize.

However, the bill’s passage could serve as a springboard toward even more ambitious metals reuse and recycling programs that could help meet the needs of the green energy transition. With Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’s Green New Deal plan calling for tomorrow’s wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries to be built with “as many recycled materials as possible,” it seems unlikely this bill will be the last word on the matter.