Here’s the latest video from National Geographic‘s year-long series on population (set to music that’s got me feeling all jittery and peppy):

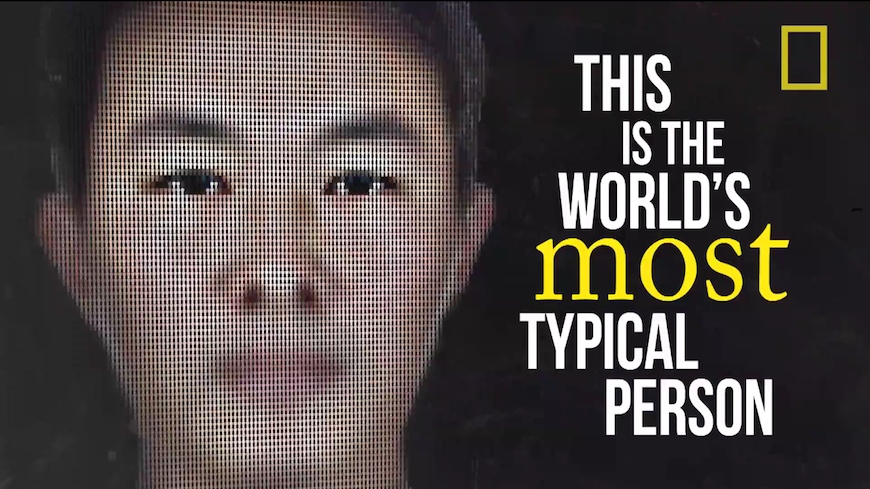

The gist: The most typical person on the planet is a 28-year-old Han Chinese man; there are more than 9 million such chaps living right now. Here’s what he looks like:

Also as part of NatGeo‘s population series, this month’s print magazine has an article by Elizabeth Kolbert on how “human beings have so altered the planet in just the past century or two that we’ve ushered in a new epoch: the Anthropocene.”

“The pattern of human population growth in the twentieth century was more bacterial than primate,” biologist E. O. Wilson has written. Wilson calculates that human biomass is already a hundred times larger than that of any other large animal species that has ever walked the Earth. …

Probably the most significant change [wrought by humans on the planet], from a geologic perspective, is one that’s invisible to us — the change in the composition of the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide emissions are colorless, odorless, and in an immediate sense, harmless. But their warming effects could easily push global temperatures to levels that have not been seen for millions of years. Some plants and animals are already shifting their ranges toward the Poles, and those shifts will leave traces in the fossil record. Some species will not survive the warming at all. Meanwhile rising temperatures could eventually raise sea levels 20 feet or more.

Long after our cars, cities, and factories have turned to dust, the consequences of burning billions of tons’ worth of coal and oil are likely to be clearly discernible. As carbon dioxide warms the planet, it also seeps into the oceans and acidifies them. Sometime this century they may become acidified to the point that corals can no longer construct reefs, which would register in the geologic record as a “reef gap.” Reef gaps have marked each of the past five major mass extinctions. The most recent one, which is believed to have been caused by the impact of an asteroid, took place 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period; it eliminated not just the dinosaurs, but also the plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and ammonites. The scale of what’s happening now to the oceans is, by many accounts, unmatched since then. To future geologists, [British stratigrapher Jan] Zalasiewicz says, our impact may look as sudden and profound as that of an asteroid.

Ka-boom.

For more in this vein, check out my post on National Geographic‘s January population cover story.

This is the latest in a series of Saturday GINK videos about population and reproduction (or a lack thereof).