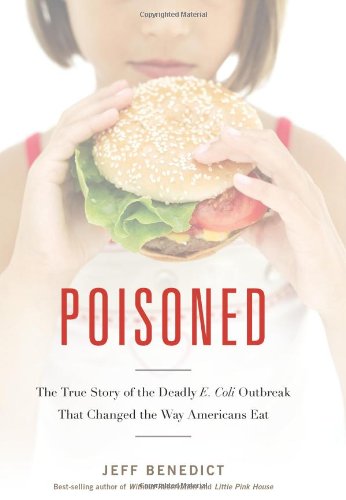

Double your trouble.Photo: theimpulsivebuyFor most of us working in food policy, it’s hard to remember a time when food outbreaks of bugs like E. coli didn’t happen pretty much weekly. But reading the new book Poisoned by Jeff Benedict made me realize that bacteria-contaminated hamburgers are a relatively recent phenomenon. It’s a striking reminder of how our food system has gone very, very wrong.

Double your trouble.Photo: theimpulsivebuyFor most of us working in food policy, it’s hard to remember a time when food outbreaks of bugs like E. coli didn’t happen pretty much weekly. But reading the new book Poisoned by Jeff Benedict made me realize that bacteria-contaminated hamburgers are a relatively recent phenomenon. It’s a striking reminder of how our food system has gone very, very wrong.

Given that the first headline-grabbing E. coli outbreak — the Jack in the Box debacle of 1993 — happened so long ago, it seems odd that no one has devoted a book to the topic before. But it’s just as well, because Benedict’s style is tailor-made to the task. His detailed and heart-wrenching story-telling makes the 18-year wait well worthwhile.

Each chapter tells the tale from the varying perspectives of several key players: from the parents of the victims, to the corporate executives, to the lawyers on both sides of the inevitable spate of lawsuits. But instead of relying on the past tense to tell their respective stories, Benedict chooses a novel-like style, with events unfolding in “real time.”

Within just a few pages, the reader is swiftly taken from the bedside of 9-year-old Brianne Kiner suffering from a bacteria-induced coma, to the office of Jack in the Box CEO Robert Nugent, wondering if the company would survive this PR disaster, to the laboratory of Dr. John Kobayashi, epidemiologist in the Washington State Health Department, where test results confirmed the source of the deadly contamination and how he decides to go public to prevent more victims.

Within just a few pages, the reader is swiftly taken from the bedside of 9-year-old Brianne Kiner suffering from a bacteria-induced coma, to the office of Jack in the Box CEO Robert Nugent, wondering if the company would survive this PR disaster, to the laboratory of Dr. John Kobayashi, epidemiologist in the Washington State Health Department, where test results confirmed the source of the deadly contamination and how he decides to go public to prevent more victims.

The result is a fast-paced, incredibly readable, even if at times a tad overly dramatized, story. (To be fair, it’s difficult to charge someone with overstating tragedy when it comes to the death of children.)

The author keeps coming back to one key player’s story: personal injury attorney Bill Marler, a name familiar to anyone who keeps up on food safety. But in 1993, Marler, like most other Americans, had never even heard of E. coli. When the news hit that contaminated fast food burgers were causing scores of admissions to Seattle hospitals, Marler’s career path was set into motion.

Since then, Marler Clark (“The Food Safety Law Firm”) has represented thousands of victims of foodborne illness outbreaks. But far more than a plaintiff’s firm, Marler and his colleagues also advocate for better food safety laws. (For example, last year Marler begged Congress to “put a trial lawyer out of business” by increasing FDA’s authority and scope, which finally did happen.)

Two aspects of this disaster stood out as particularly startling from a food policy perspective. At least a year prior to the outbreak, Washington state had issued new regulations requiring restaurants to cook its hamburgers to a higher temperature than was required by federal law. But somehow that detail was missed by Jack in the Box execs. (The quality-control executive who blamed himself for not knowing about the new rule actually comes off as sympathetic, as do other employees.)

The other startling fact was that the federal government (USDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) had known for at least 10 years prior that E. coli could be transmitted through hamburgers. Two outbreaks linked to “undercooked meat” causing multiple illnesses from a single, unnamed chain were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1983, and yet the public was unaware of this incident (which occurred in 1982). The chain was McDonald’s. While it’s obvious why the company didn’t want this information to be made public, executives apparently didn’t even bother to share it within their own industry. Jack in the Box’s CEO lamented that had he known, his company might have taken additional precautions.

To its credit, Jack in the Box subsequently hired a meat-safety specialist to implement stepped-up “quality assurance” measures. Also, the company did not put up much of a fight in court. To the contrary, Jack in the Box (through its insurers) ultimately paid out record-breaking settlement amounts, thanks in large part to some very gutsy negotiating by Bill Marler.

In an especially revealing section, the book tells the inside story at Jack in the Box. You might expect the executives to be painted as the bad guys, but that’s hardly the case. These are just ordinary businessmen caught up in an awful mess, doing their best to figure out what went wrong.

Who was to blame for the outbreak in the first place? While it was traced to a beef supplier to Jack in the Box, those details are not entirely clear; this was the one area where the book was lacking. We now know that such outbreaks are due mainly to factory farms that create unsanitary conditions for animals, spurred by widespread distribution and lack of oversight.

But the heart and soul of the book lies with the victims and their families. When the damage was done, four children were killed and hundreds more sickened. No amount of settlement money could compensate for those losses and the author could only portray a small fraction of their actual suffering.

While the book’s subtitle (“The True Story of the Deadly E. coli Outbreak That Changed the Way Americans Eat”) may be overly optimistic, Poisoned is an extremely important account of a heart-breaking story — one that unfortunately continues to be repeated all too often.